Child and Infant Mortality

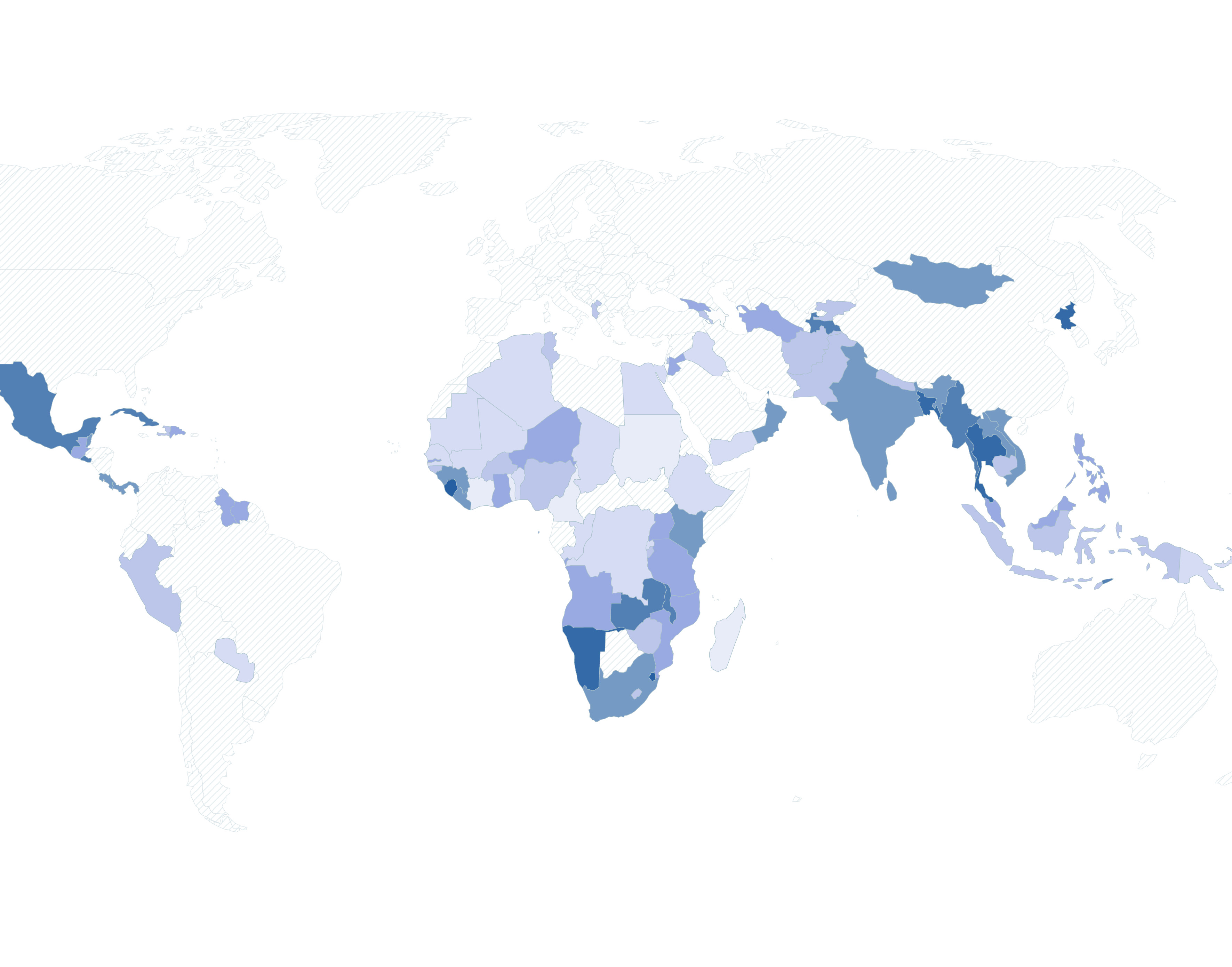

Child mortality is one of the world’s largest problems. Around 6 million children under 15 die per year. That’s around 16,000 deaths every day, or 11 every minute.

This devastating statistic reveals the vast number of children whose lives end before they can discover their talents, passions, and dreams as they grow older – and represents the impact of child mortality on so many people’s lives: parents, siblings, families, and communities.

What’s tragic is how many of these deaths are preventable. Most are caused by malnutrition, birth conditions such as preterm birth, sepsis and trauma, and infectious diseases such as pneumonia, malaria, and HIV/AIDS.

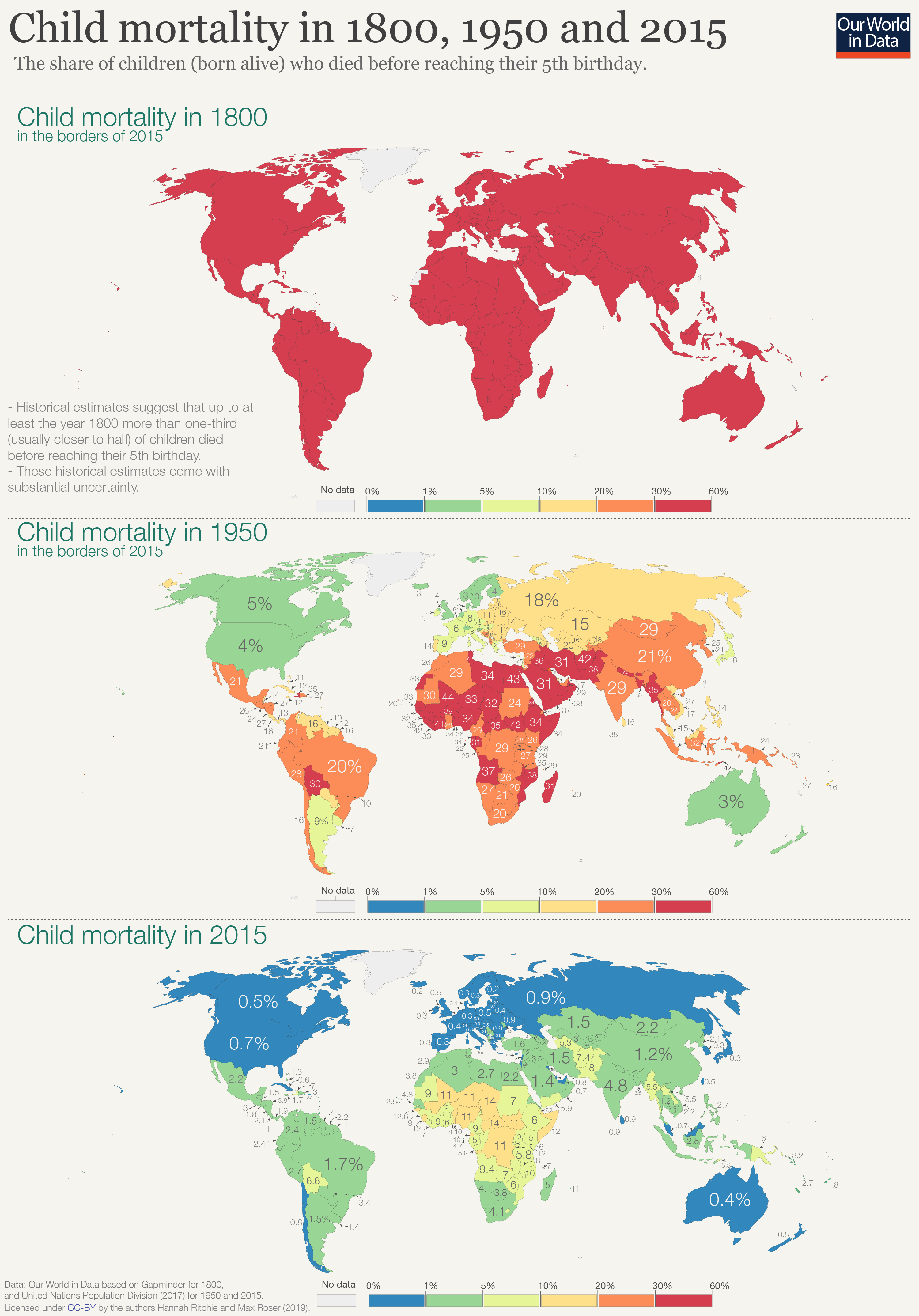

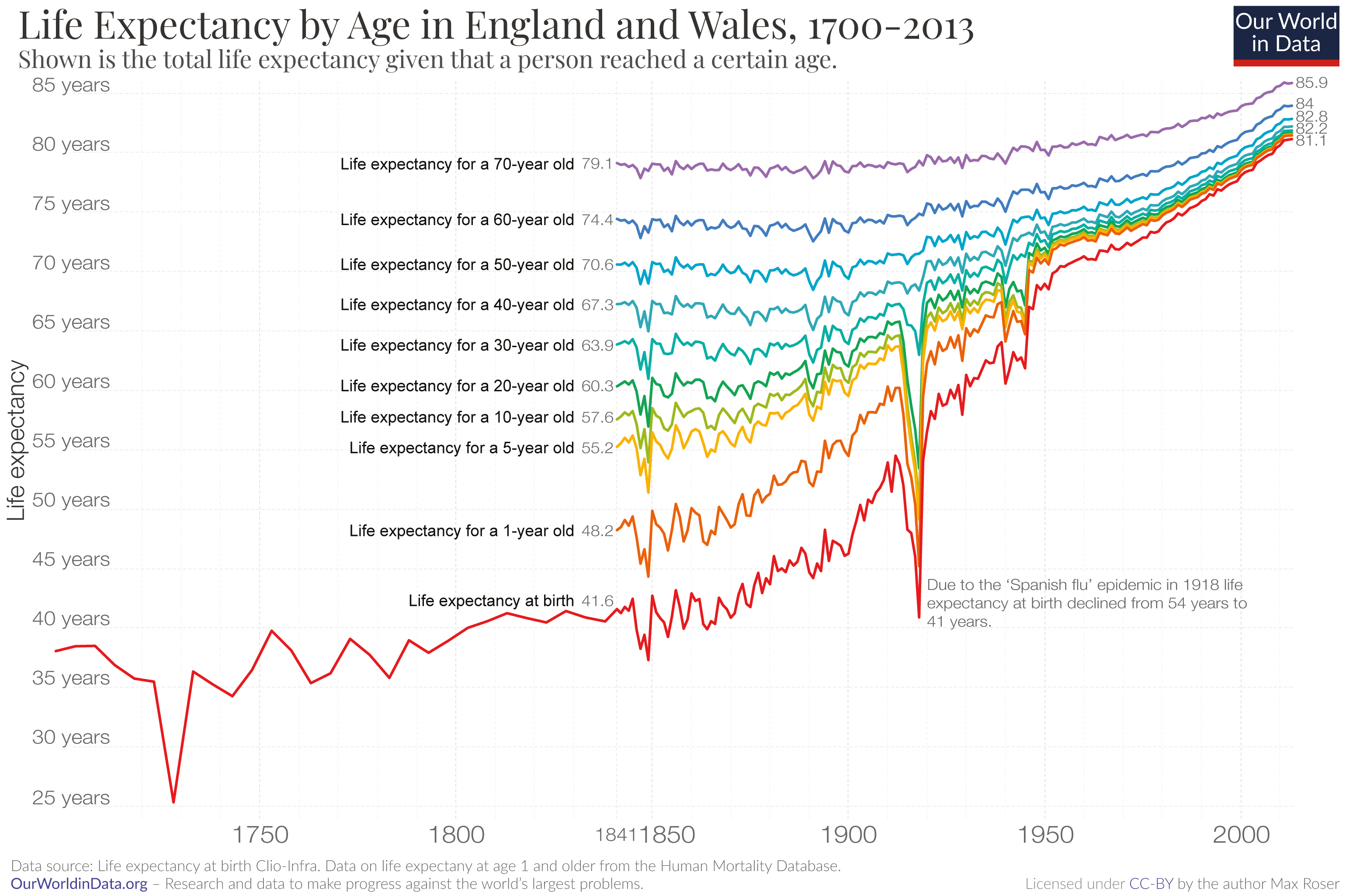

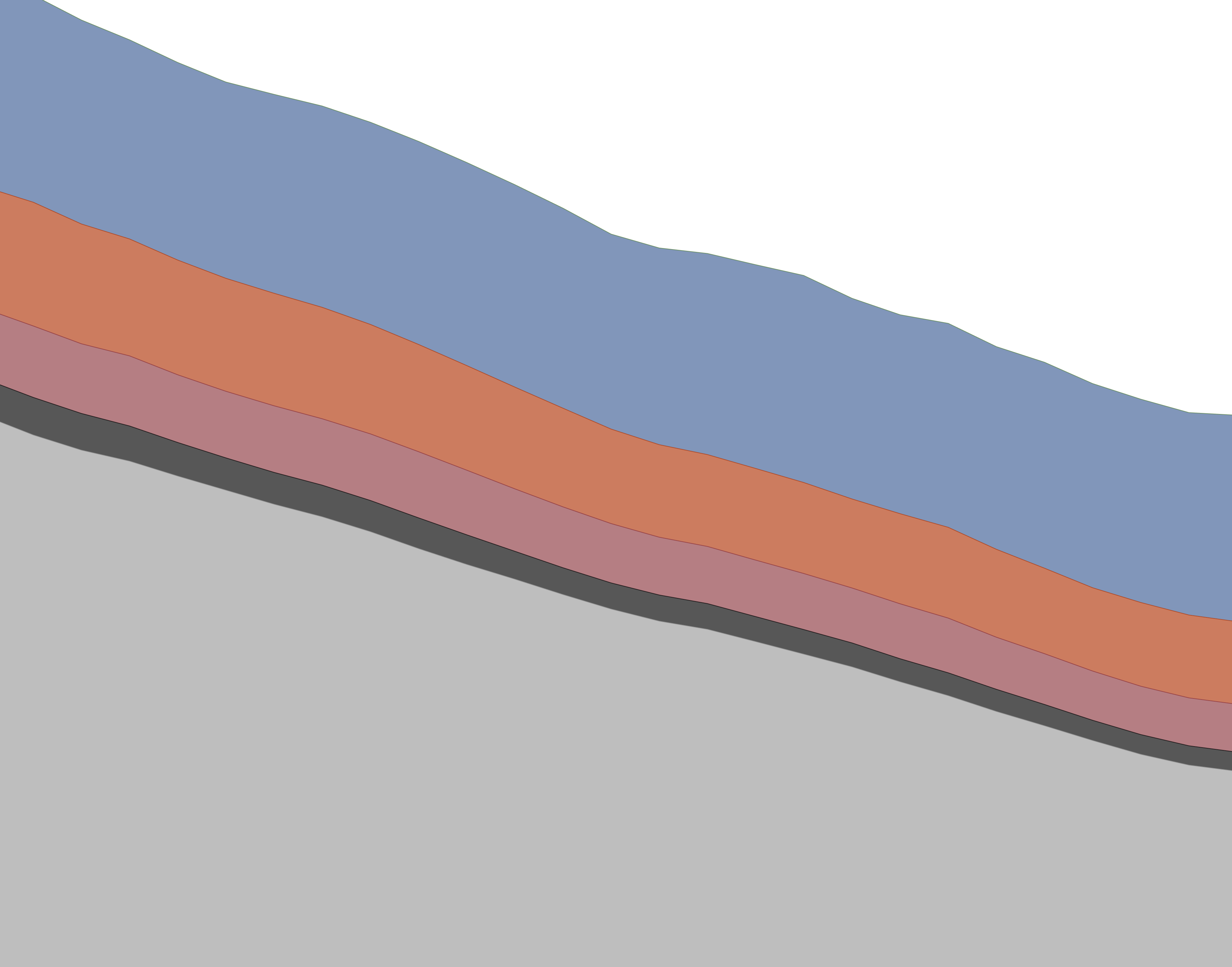

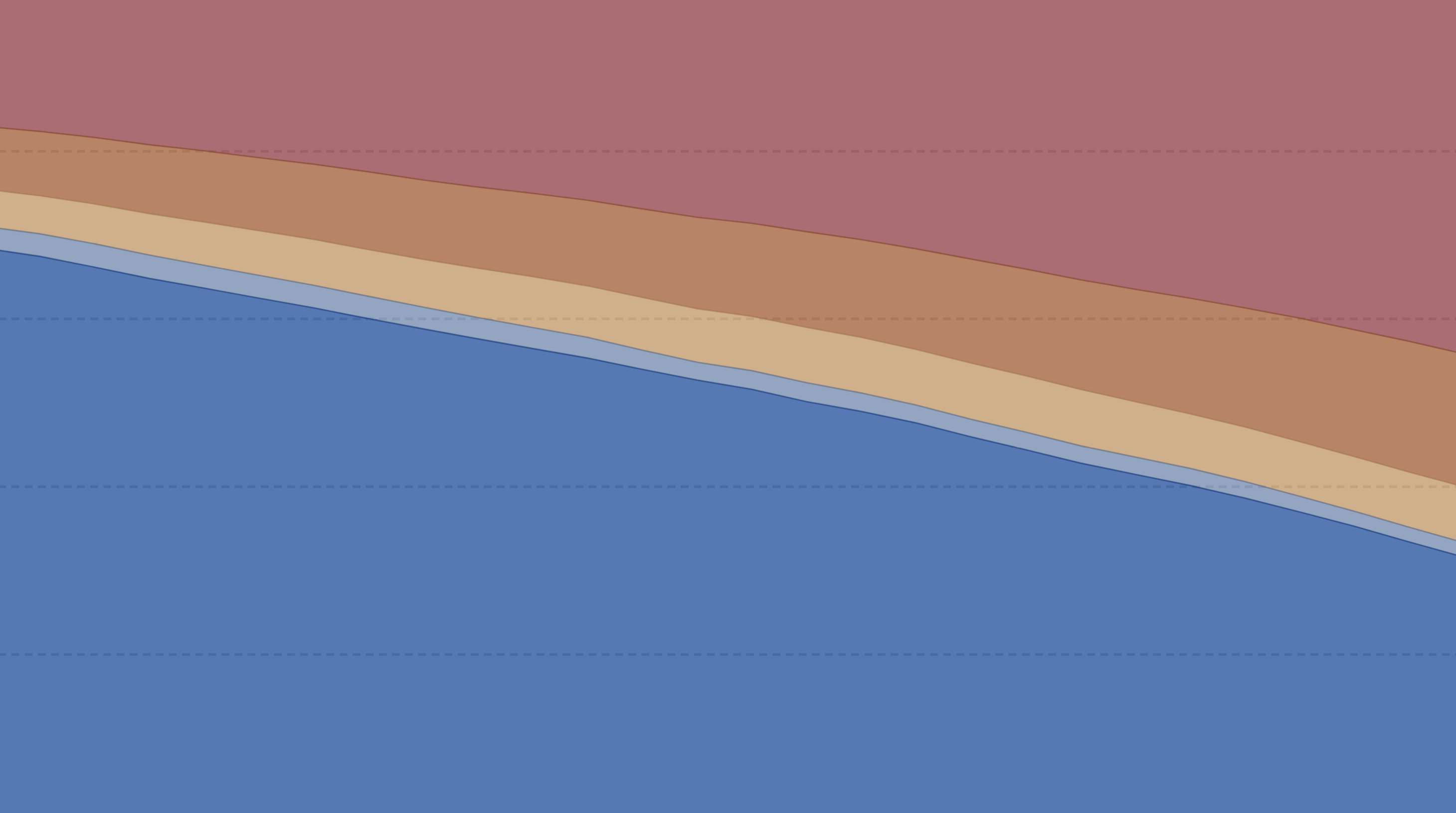

These have all declined substantially in many, but not all, parts of the world – child deaths were a grim constant in the past. For most of human history, around 1 in 2 newborns died before reaching the age of 15. By 1950, that figure had declined to around one-quarter globally. By 2020, it had fallen to 4%.

But while humanity has made much progress, there’s still a lot of work to do. To make more progress, it’s essential to have data on child mortality and its causes, and research on how to prevent it.

On this page, you will find data and research on child mortality across the world, how it has changed, its causes, and what we can do about it.

Research & Writing

More articles on child mortality

Articles on preventing child mortality

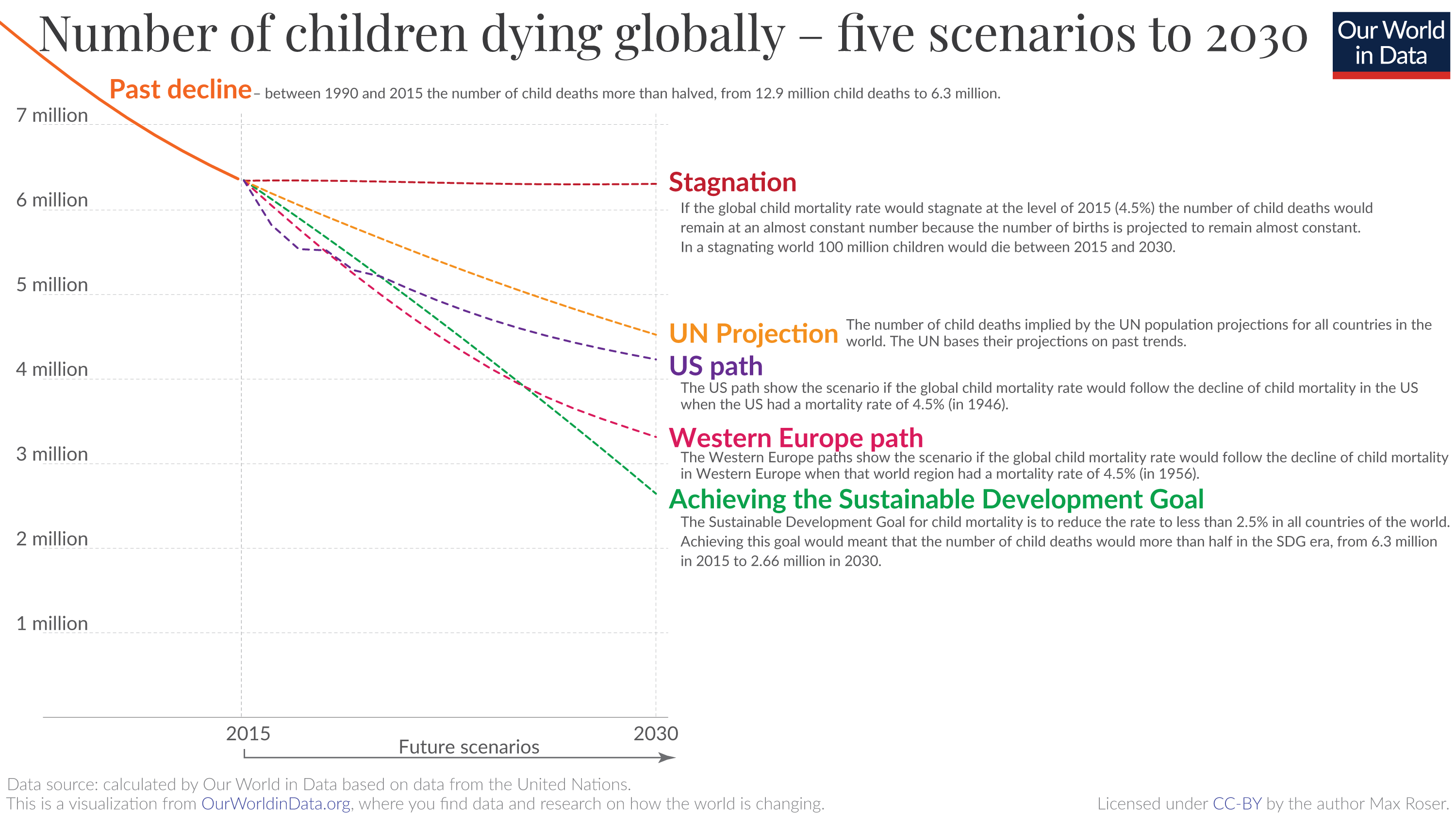

Child mortality: achieving the global goal for 2030 would be a huge achievement – but we are currently far away

Malaria: One of the leading causes of child deaths, but progress is possible and you can contribute to it

More than half a million children die from diarrhea each year. How do we prevent this?

Oral rehydration therapy: a low-tech solution that has saved millions of lives

Rotavirus vaccine – an effective tool that prevents children dying from diarrhea

Pneumonia — no child should die from a disease we can prevent

Definitions in child mortality

Endnotes

Volk, A. A., & Atkinson, J. A. (2013). Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(3), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.11.007

United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. (2022). Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2022. https://childmortality.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/UN-IGME-Child-Mortality-Report-2022.pdf

This is because HIV can be transmitted between mother and child. Bourne, D. E., Thompson, M., Brody, L. L., Cotton, M., Draper, B., Laubscher, R., Abdullah, M. F., & Myers, J. E. (2009). Emergence of a peak in early infant mortality due to HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS, 23(1), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c54bd

Ferrand, R. A., Corbett, E. L., Wood, R., Hargrove, J., Ndhlovu, C. E., Cowan, F. M., Gouws, E., & Williams, B. G. (2009). AIDS among older children and adolescents in Southern Africa: Projecting the time course and magnitude of the epidemic. AIDS, 23(15), 2039–2046. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833016ce

Hill, K., You, D., Inoue, M., Oestergaard, M. Z., & Technical Advisory Group of the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. (2012). Child Mortality Estimation: Accelerated Progress in Reducing Global Child Mortality, 1990–2010. PLoS Medicine, 9(8), e1001303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001303

See https://childmortality.org/ for more details. United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. (2022). Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2022. Available here.

In 2021, the estimated population of Ireland was 4.99 million, and Norway's was 5.41 million, according to the UN estimates. You can see more countries’ populations on our page on Population Growth.

Berrut, S., Pouillard, V., Richmond, P., & Roehner, B. M. (2016). Deciphering infant mortality. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 463, 400–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2016.07.031

Schöley, J. (2019). The age-trajectory of infant mortality in the United States: Parametric models and generative mechanisms. Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Austin, TX. Available here.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani, Fiona Spooner, Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2023) - “Child and Infant Mortality” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-child-mortality,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner and Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser},

title = {Child and Infant Mortality},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.