Human Rights

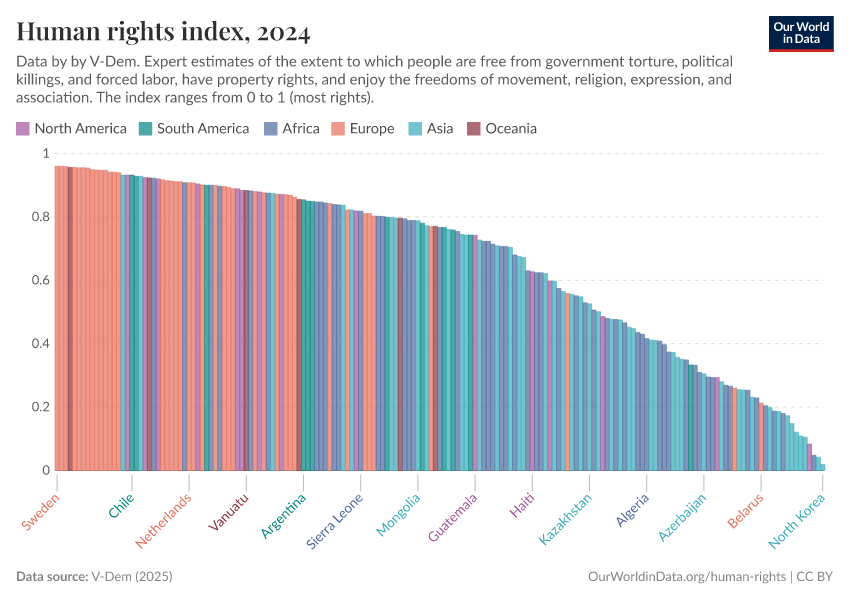

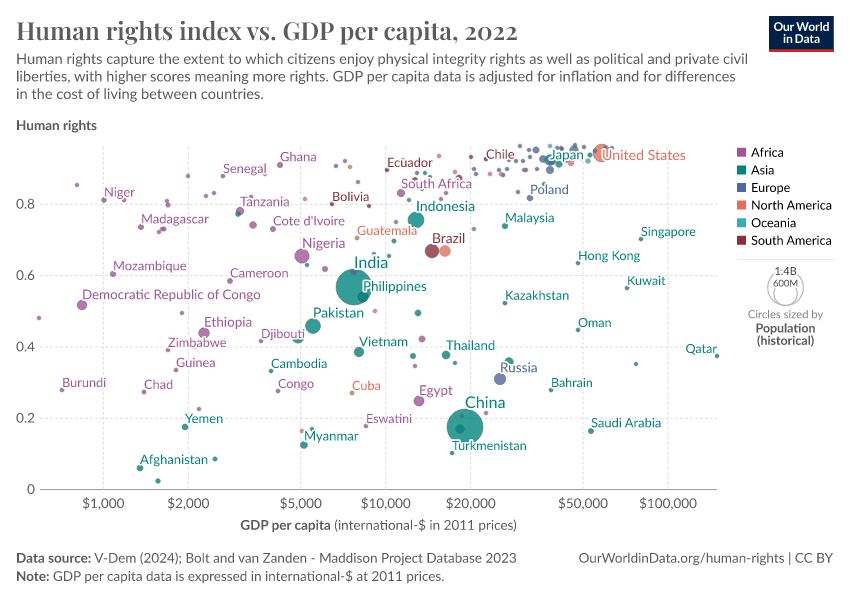

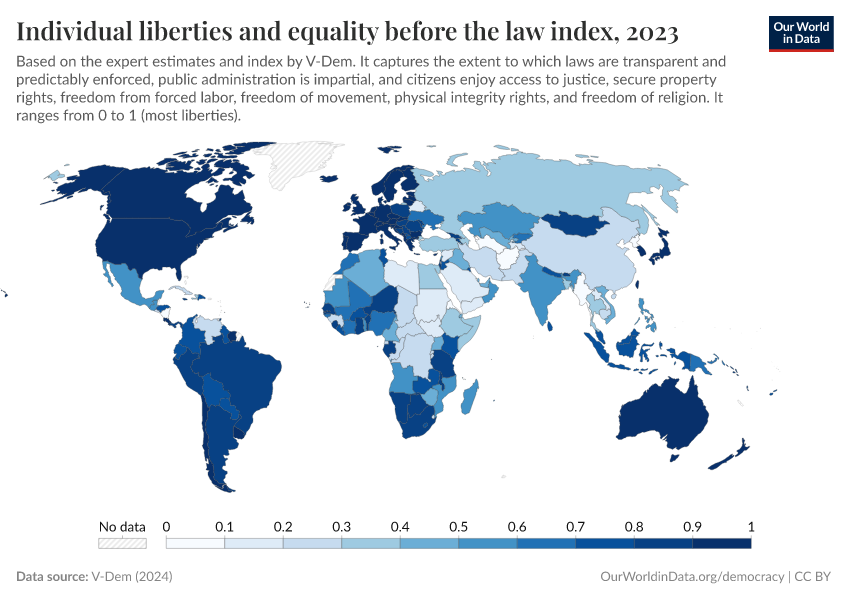

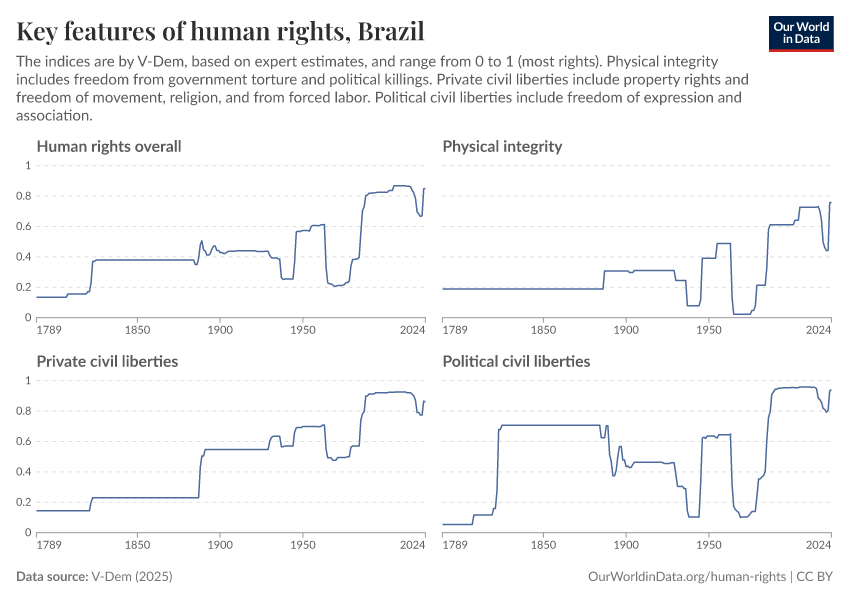

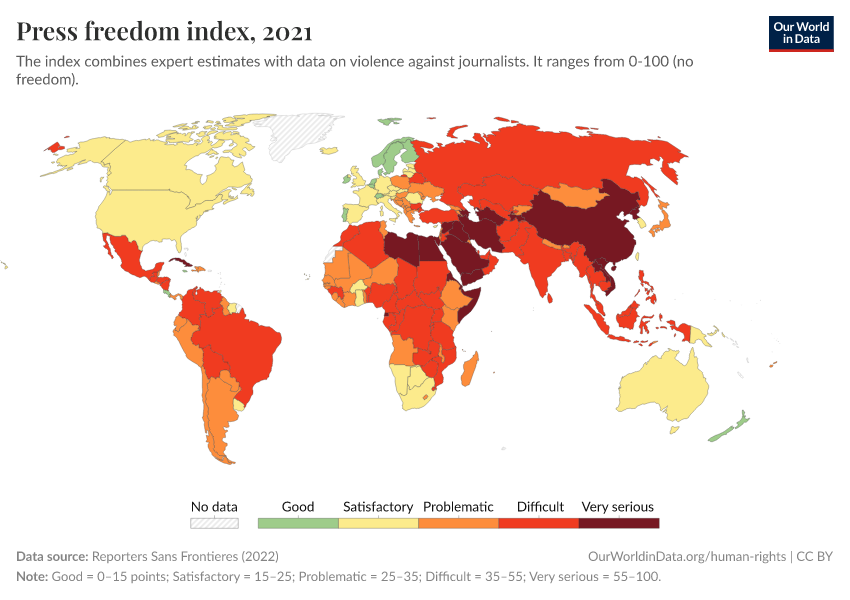

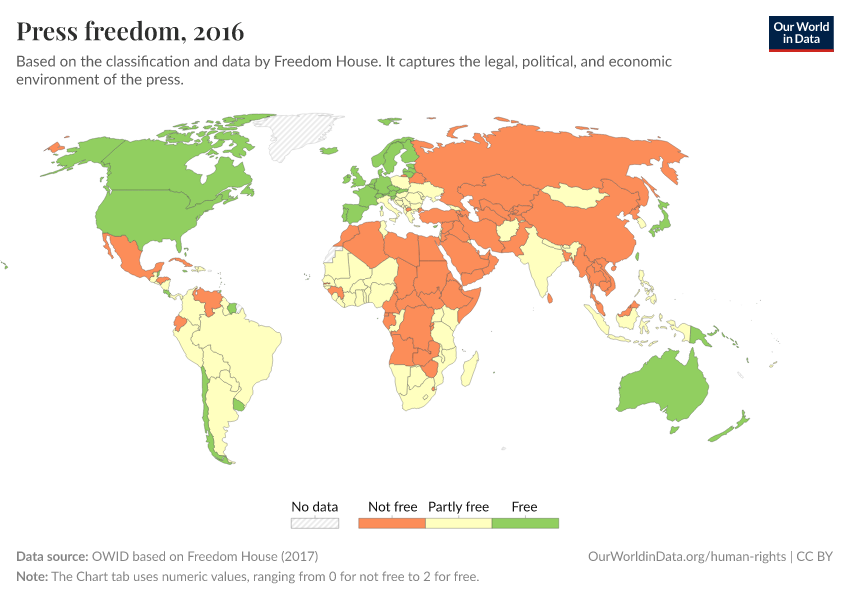

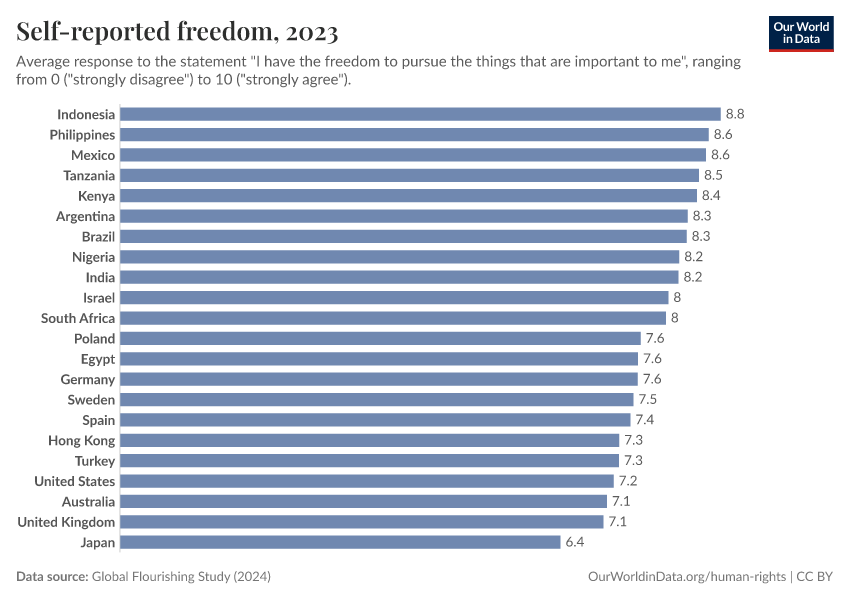

How has the protection of human rights changed over time? How does it differ across countries, and between social groups? Explore global data on human rights.

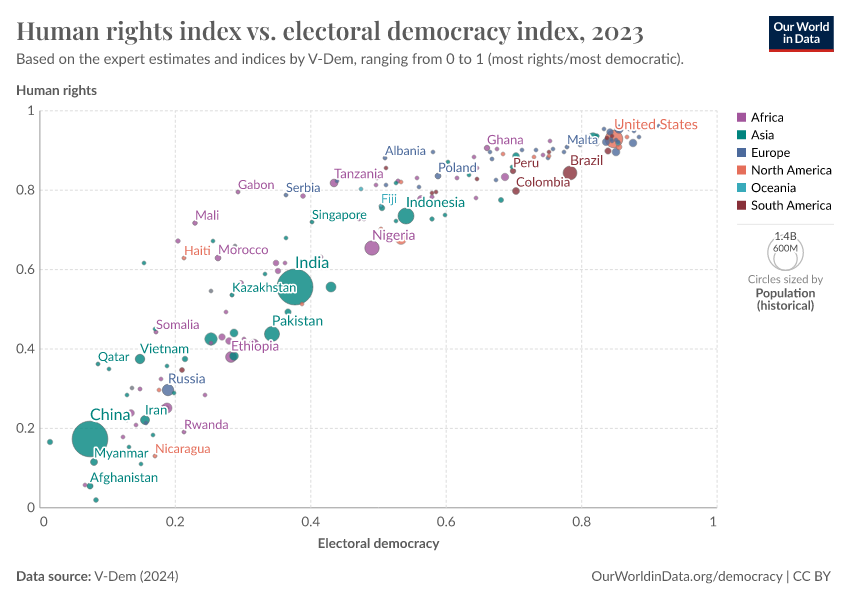

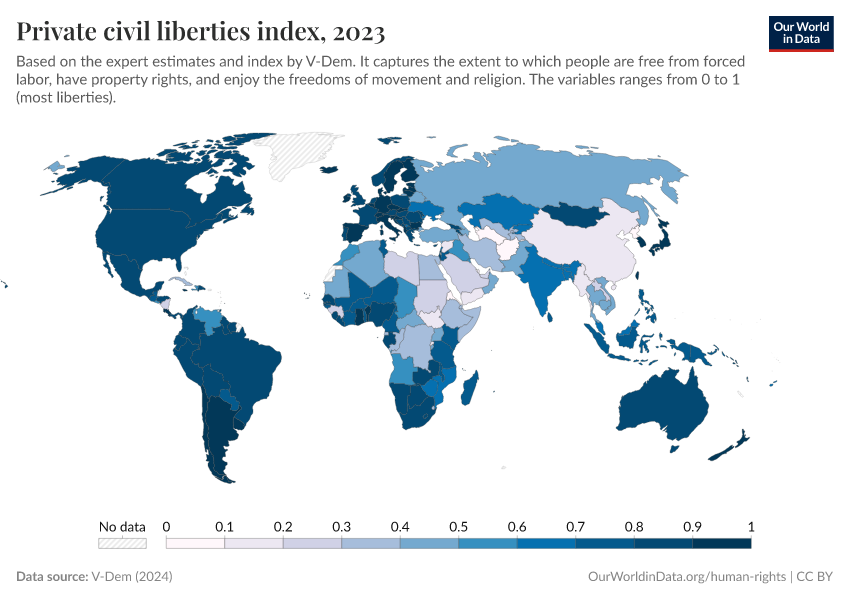

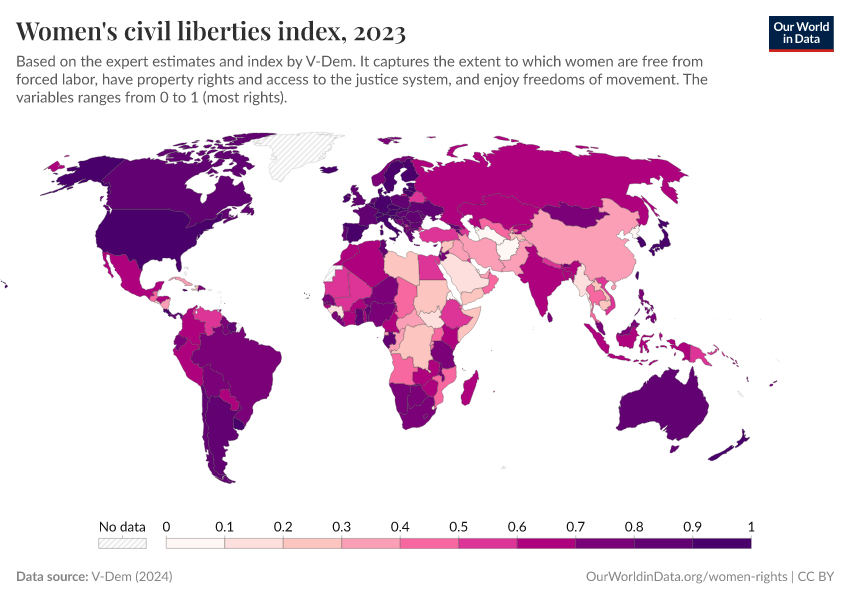

Human rights are rights that all people have, regardless of their country, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, or any other trait.

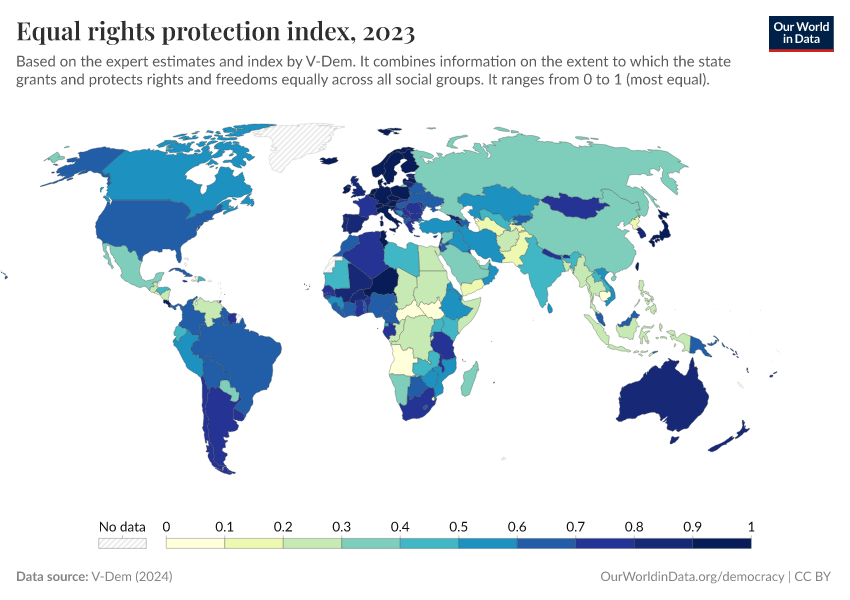

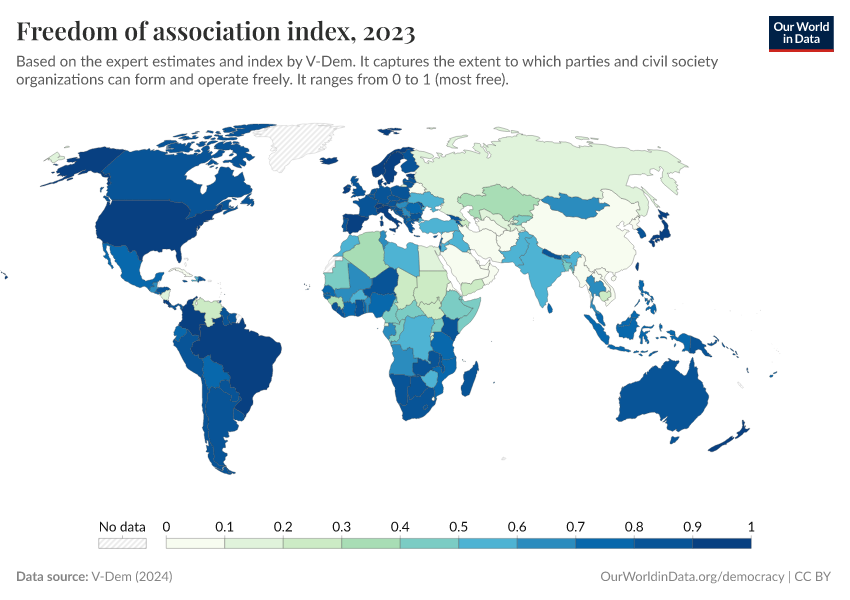

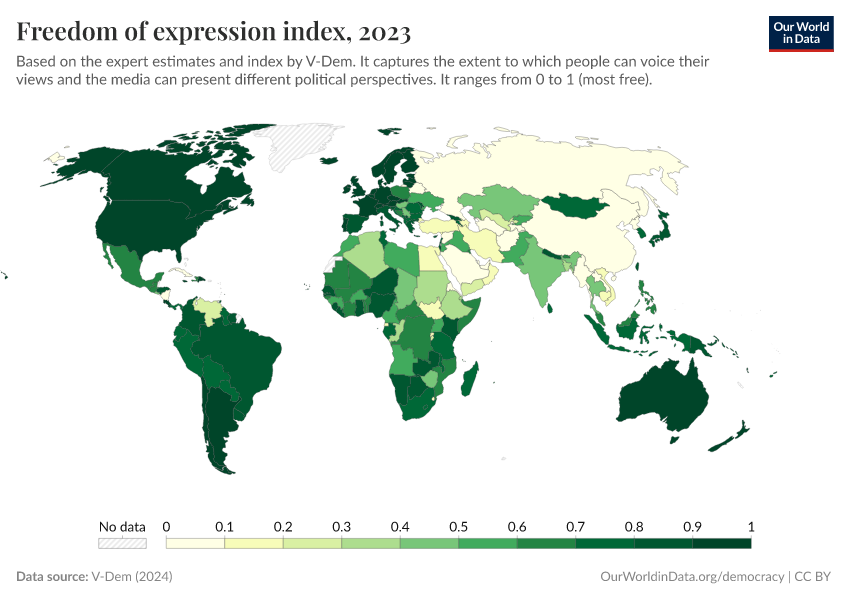

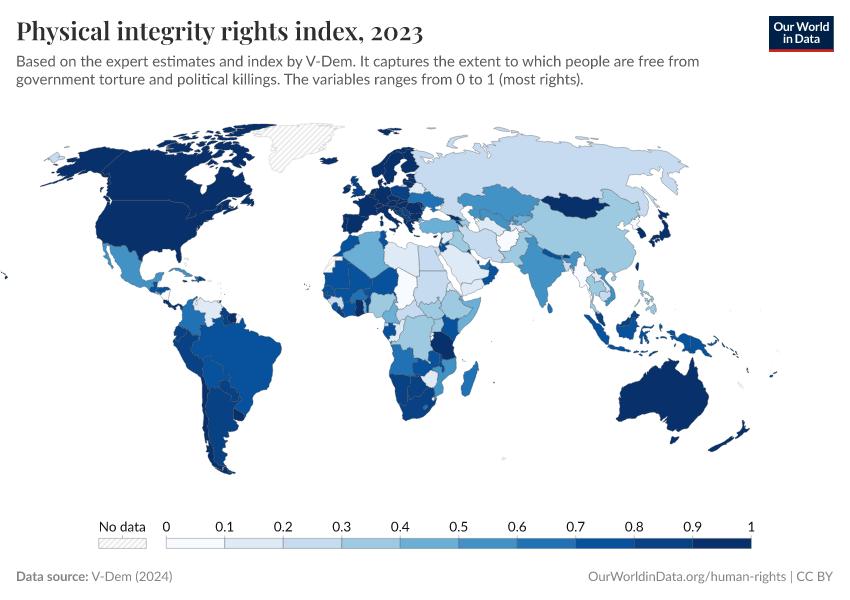

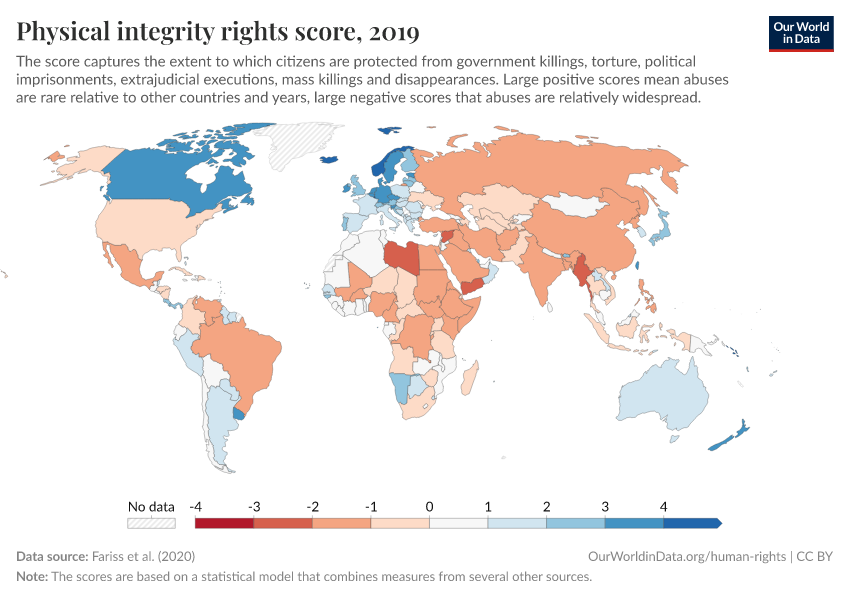

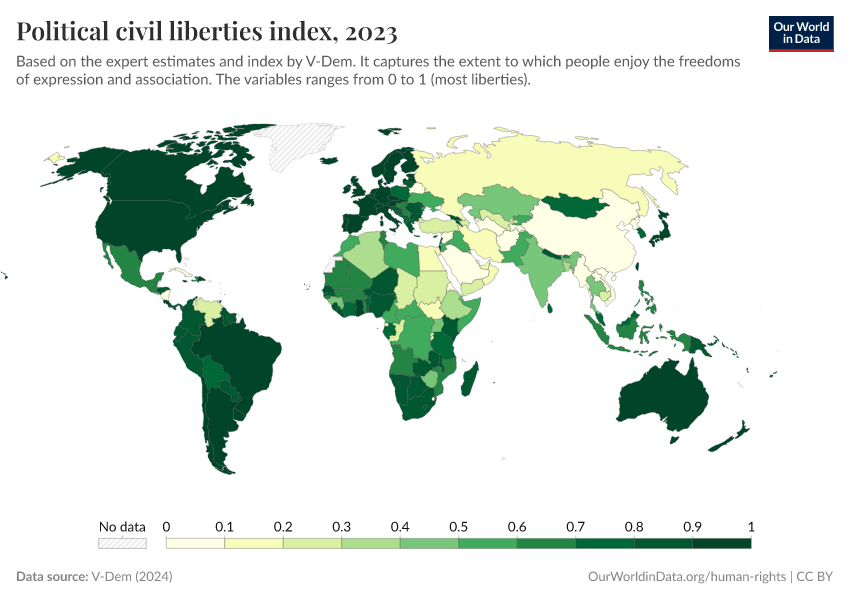

Among others, this includes: physical integrity rights, such as not being killed or tortured; civil rights, such as practicing their religion and moving freely in their country; and political rights, such as freedoms of speech and association.

The protection of these rights allows people to live the lives they want and to thrive in them.

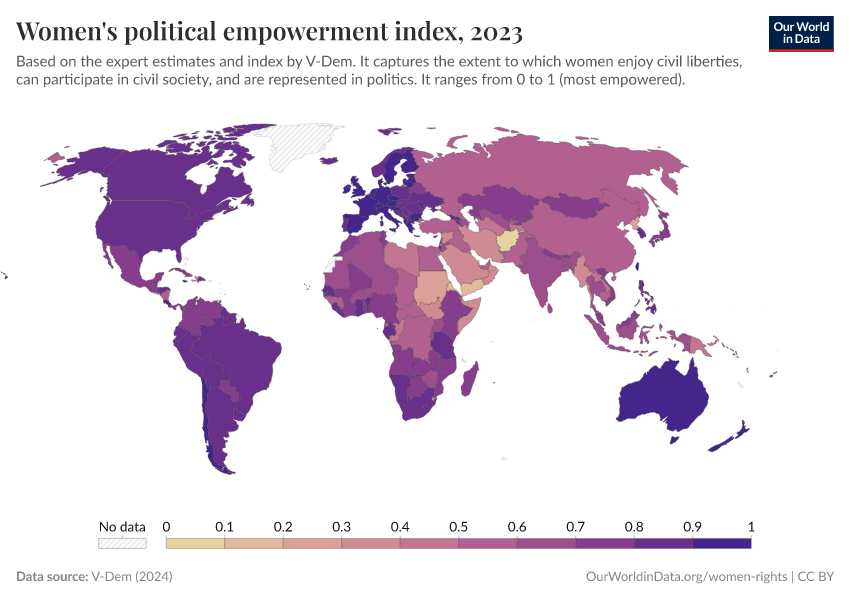

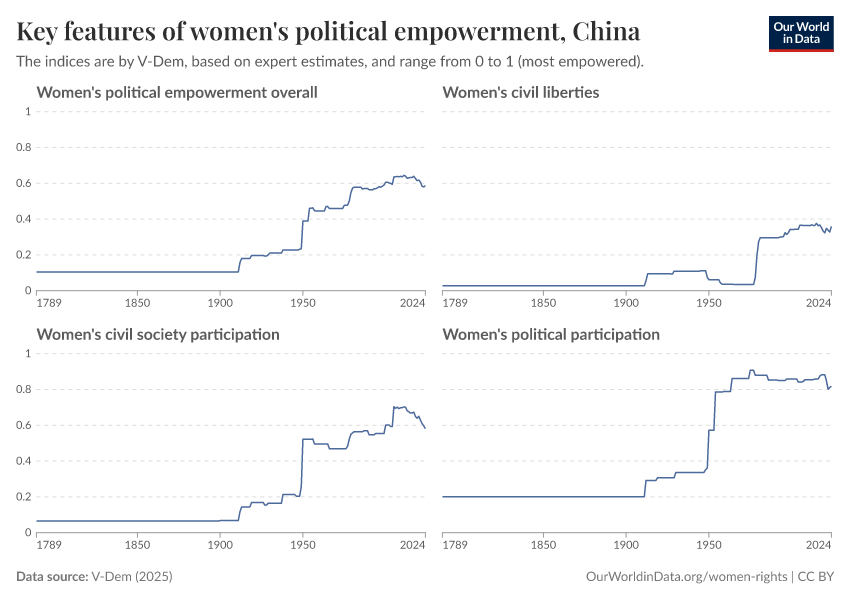

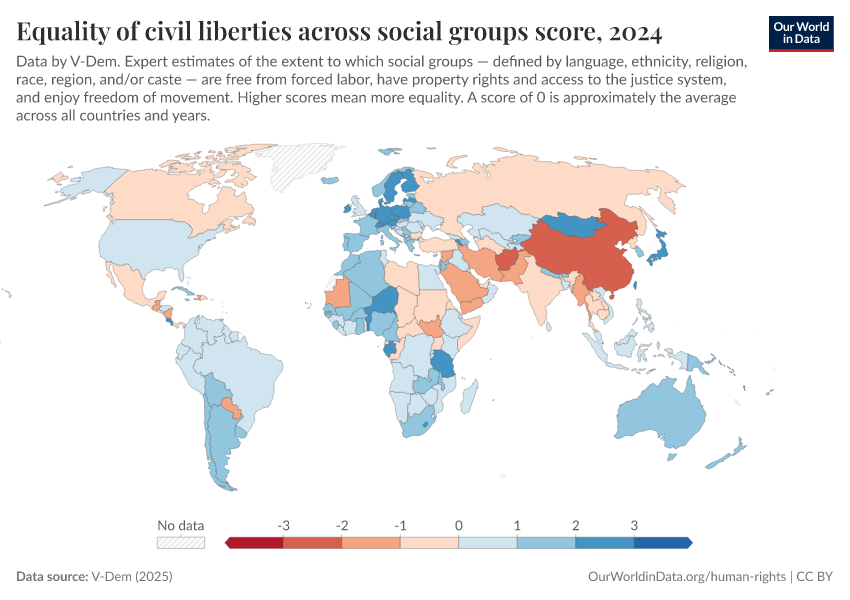

Human rights have become much more protected, but this varies a lot between countries. And not everyone enjoys the same protections: people are often marginalized because of their gender, sexuality, or ethnicity.

On this page, you can find data, visualizations, and writing on how the protection of human rights has changed over time, how it differs across countries, and how it varies between people of different genders, sexualities, and ethnicities.

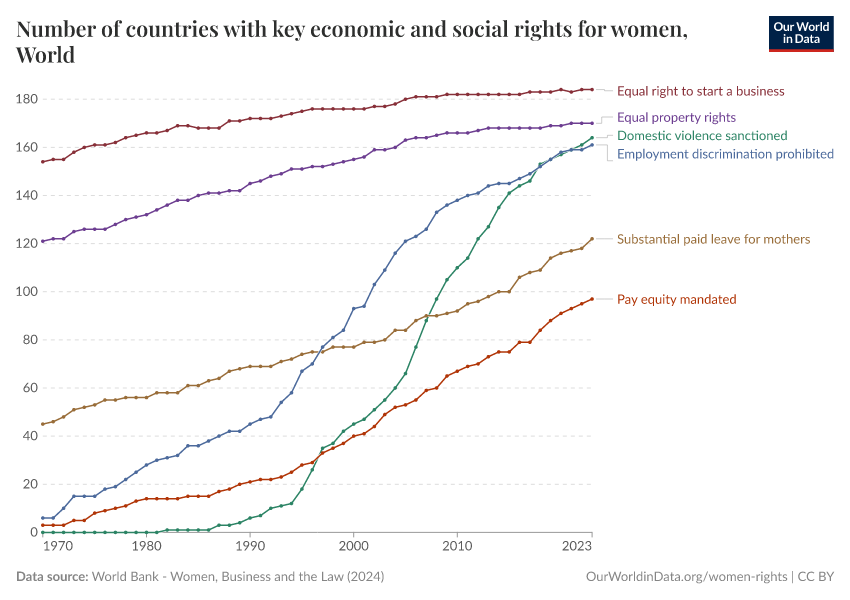

We have additional topic pages related to people’s economic and social rights, such as on food, health, and education, and dedicated topic pages for women’s rights and LGBT+ rights.

Research & Writing

March 08, 2024

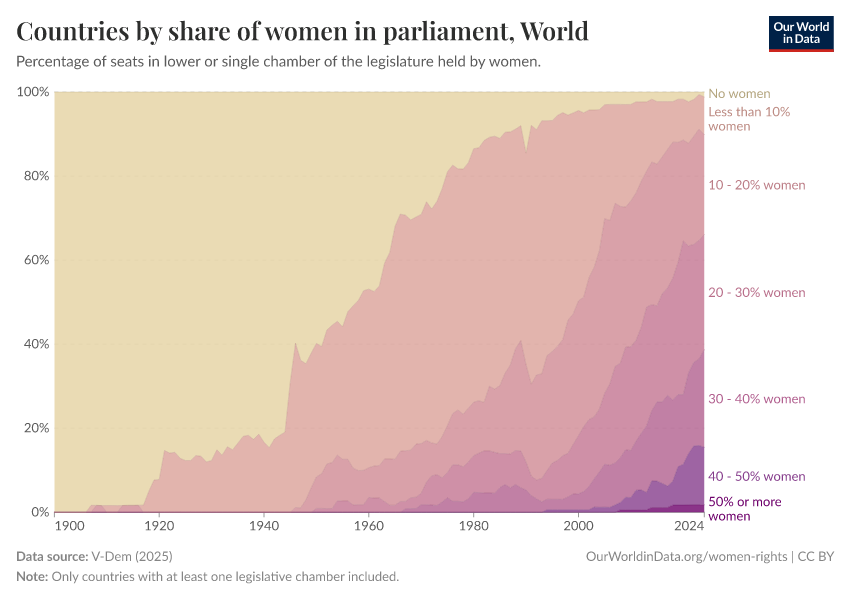

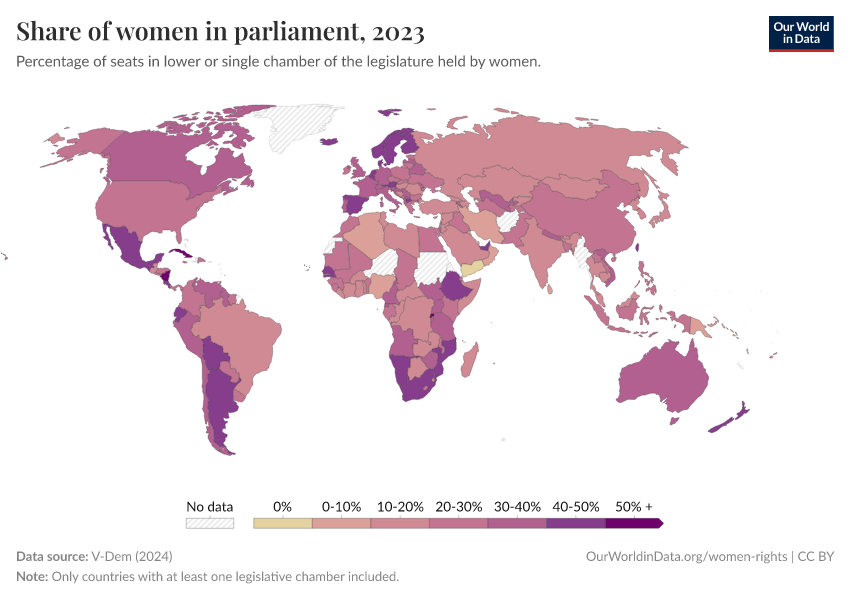

Women have made major advances in politics — but the world is still far from equal

Women have gained the right to vote and sit in parliament almost everywhere. But they remain underrepresented, especially in the highest offices.

June 24, 2024

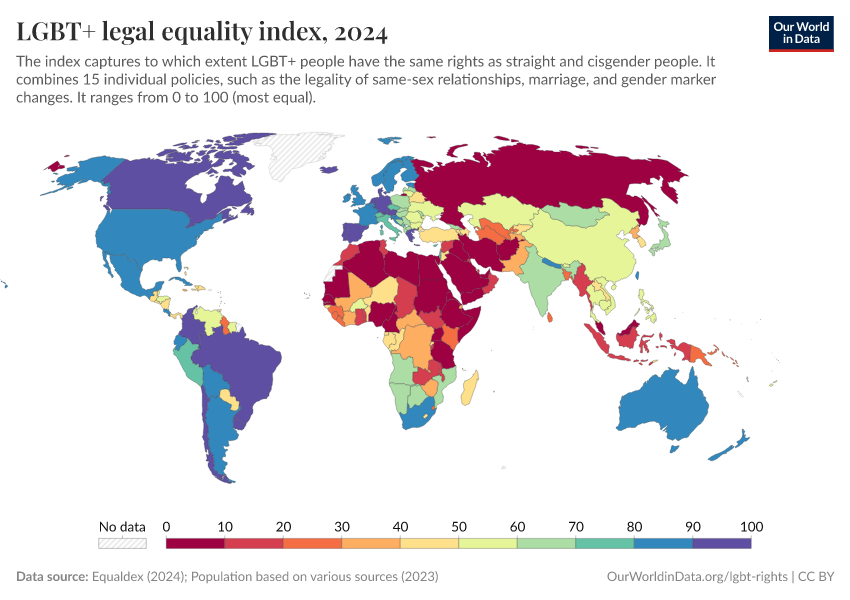

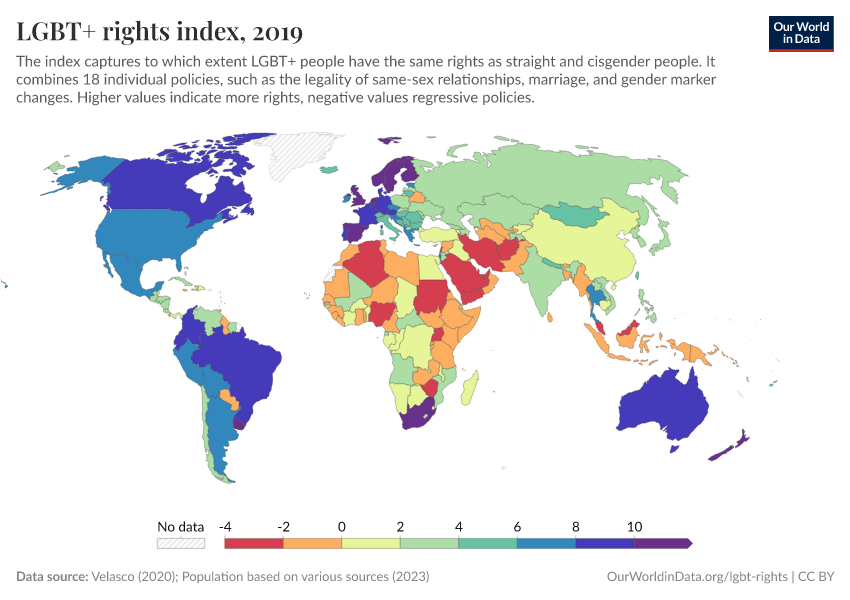

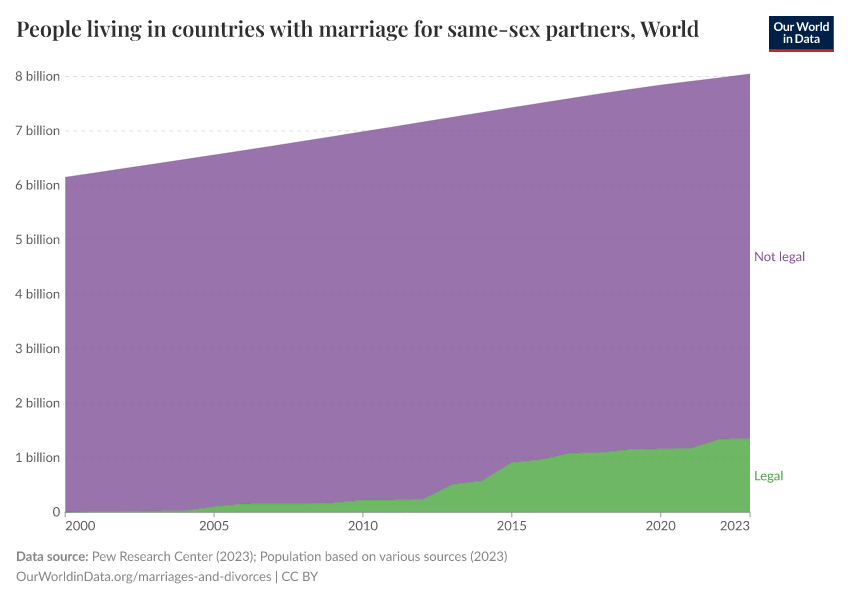

LGBT+ rights have become more protected in dozens of countries, but are not recognized across most of the world

Despite progress, same-sex marriage, adoption, gender marker changes, and third genders remain unrecognized in many countries. Some have even imposed more regressive policies.

Key Charts on Human Rights

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

This means that populous countries matter more when calculating the average than countries with small populations.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Ana Good God, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Joshua Krusell, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Natalia Natsika, Anja Neundorf, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Josefine Pernes, Oskar Rydén, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2023. V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

The score jumps in 1900 because V-Dem covers many more countries since then (which often were colonies at first).

Velasco, Kristopher. 2020. Transnational Backlash and the Deinstitutionalization of Liberal Norms: LGBT+ Rights in a Contested World.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Bastian Herre and Pablo Arriagada (2016) - “Human Rights” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/human-rights' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-human-rights,

author = {Bastian Herre and Pablo Arriagada},

title = {Human Rights},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2016},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/human-rights}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.