Diarrheal Diseases

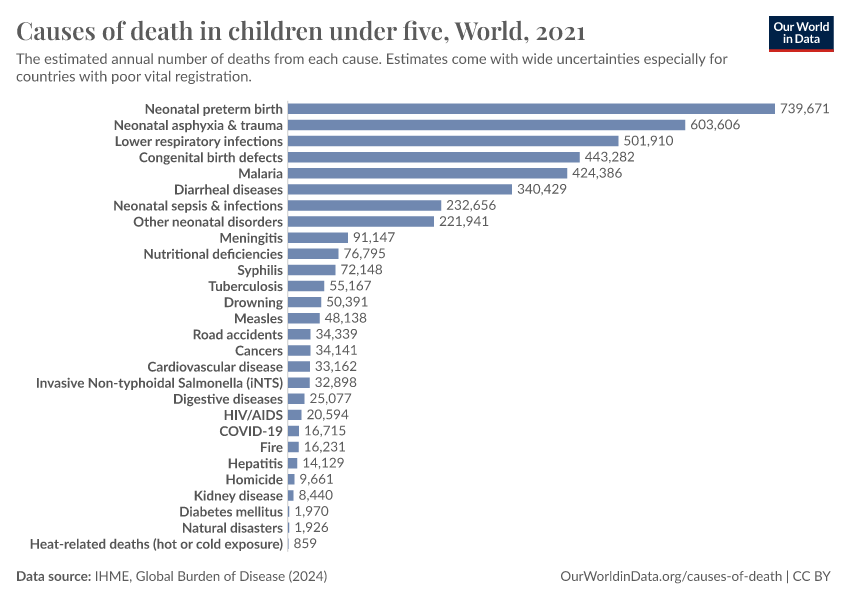

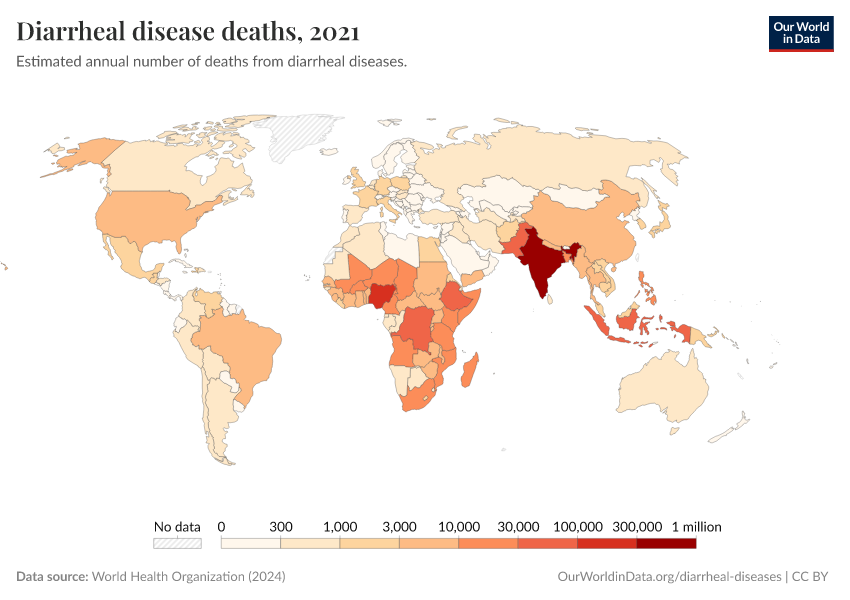

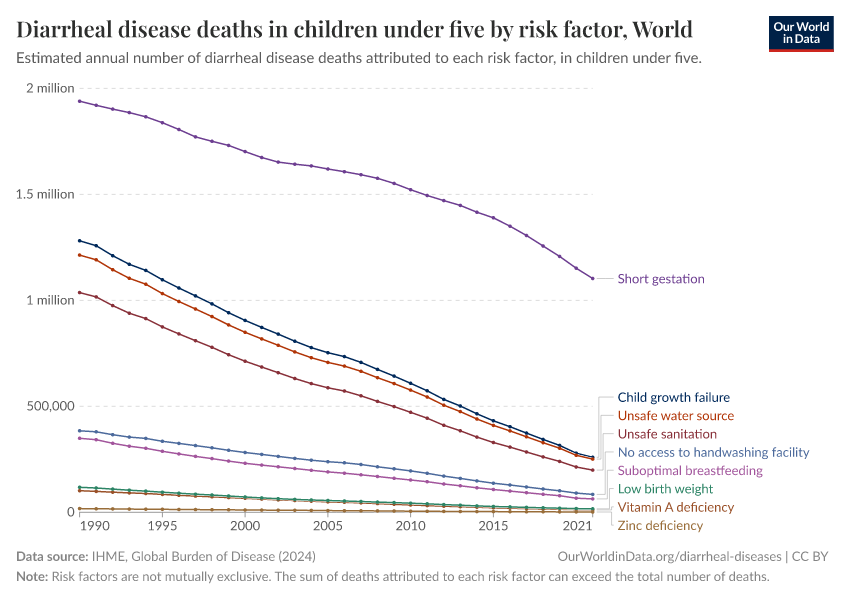

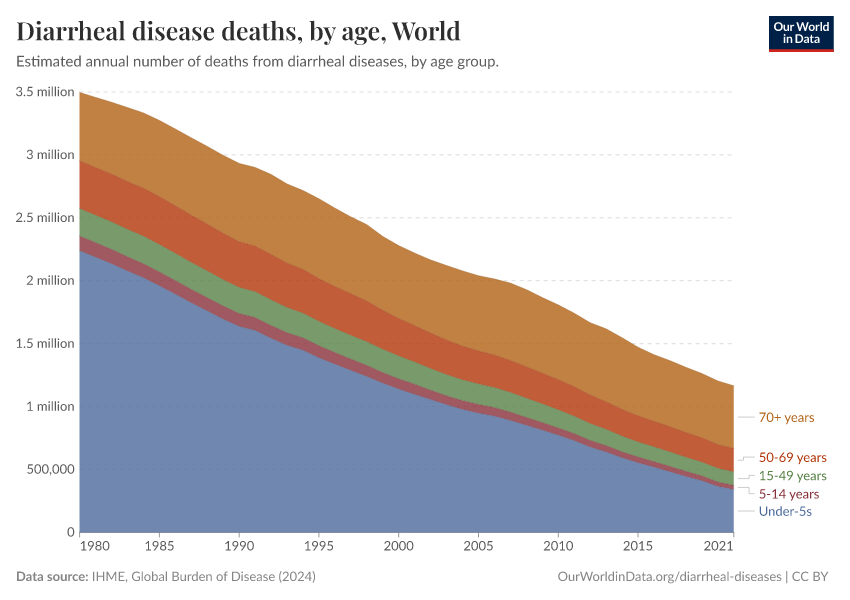

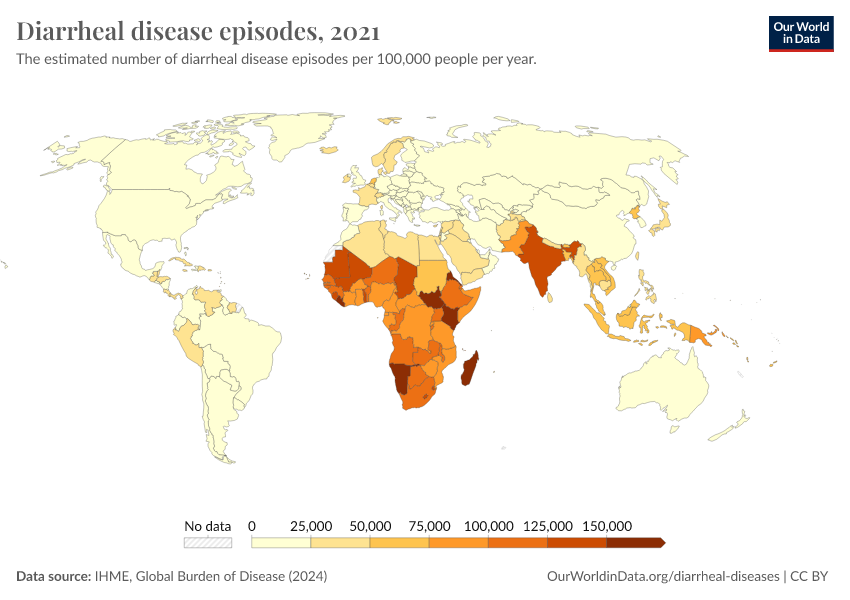

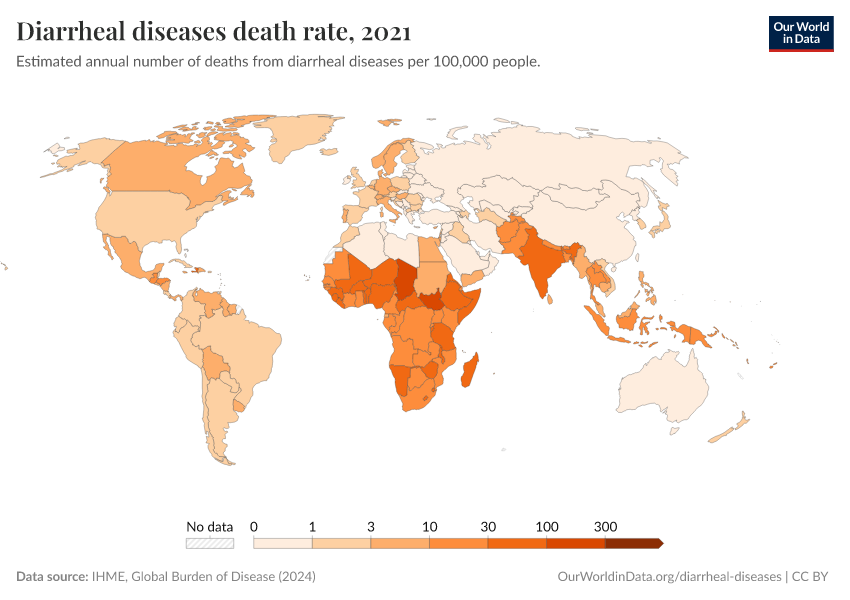

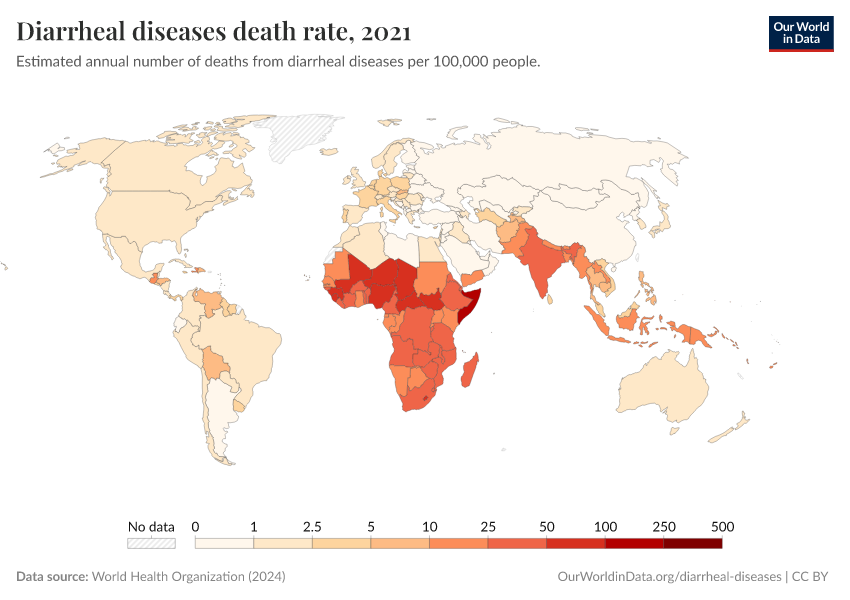

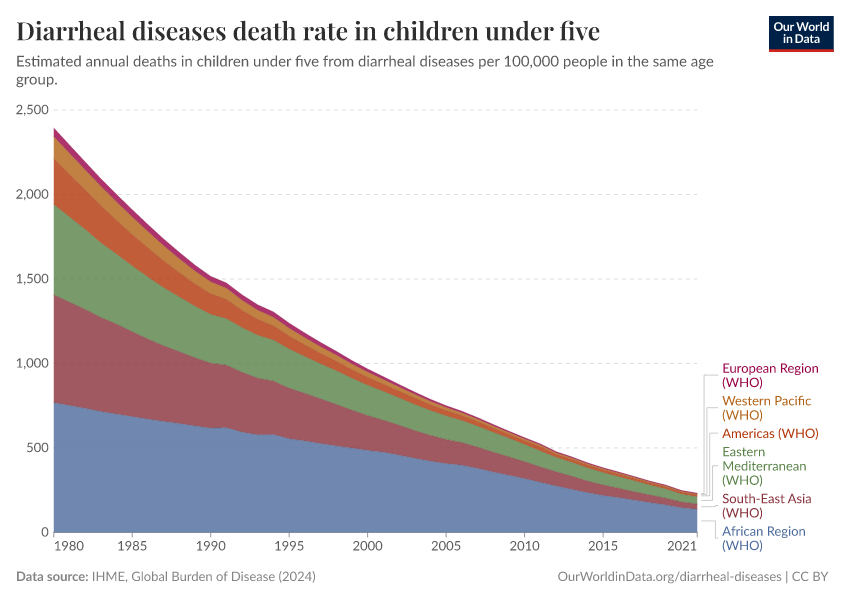

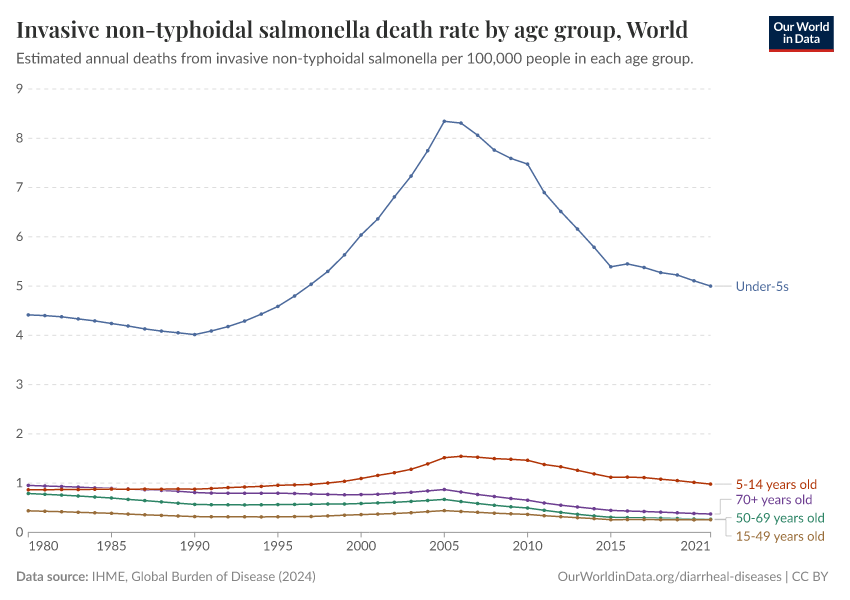

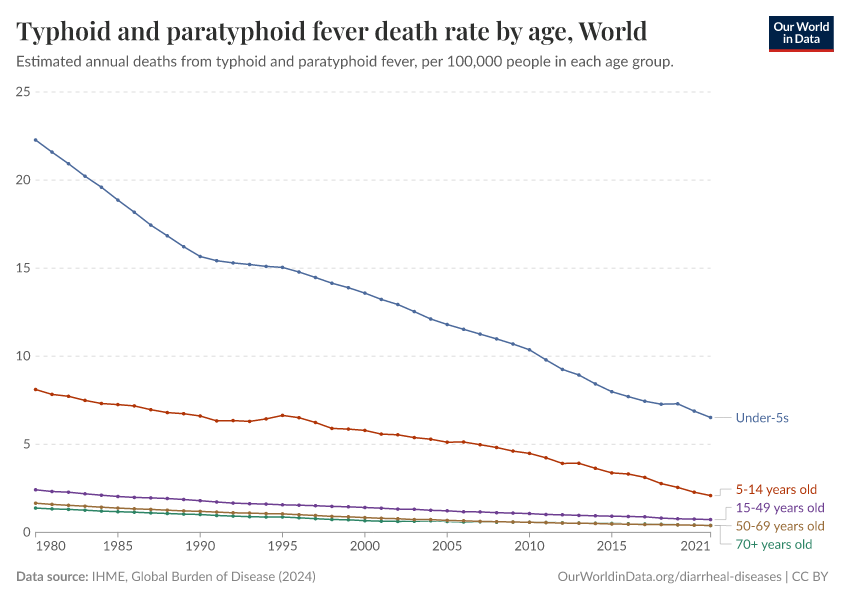

Diarrheal diseases are among the most common causes of death, especially in children.

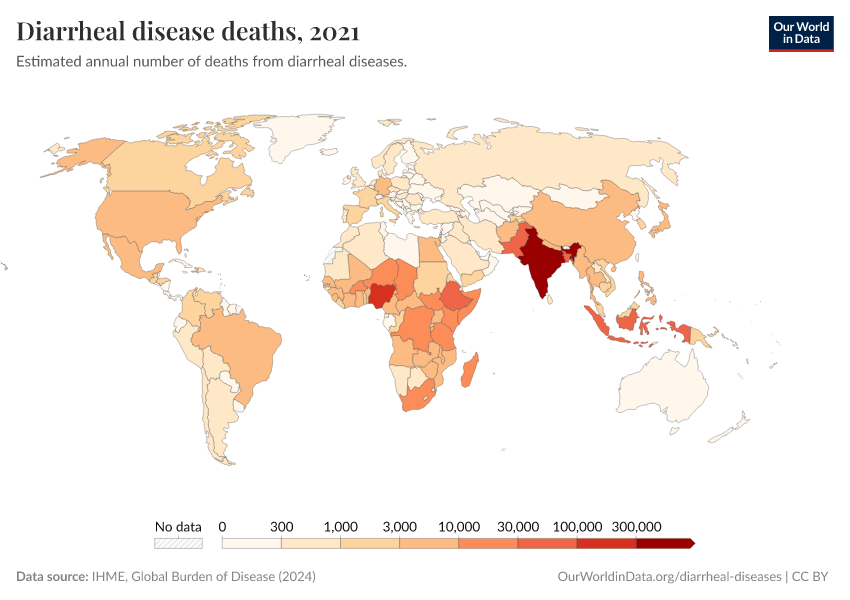

In 2021, around 1.2 million people died from diarrheal diseases. That was equivalent to all violent deaths combined.1

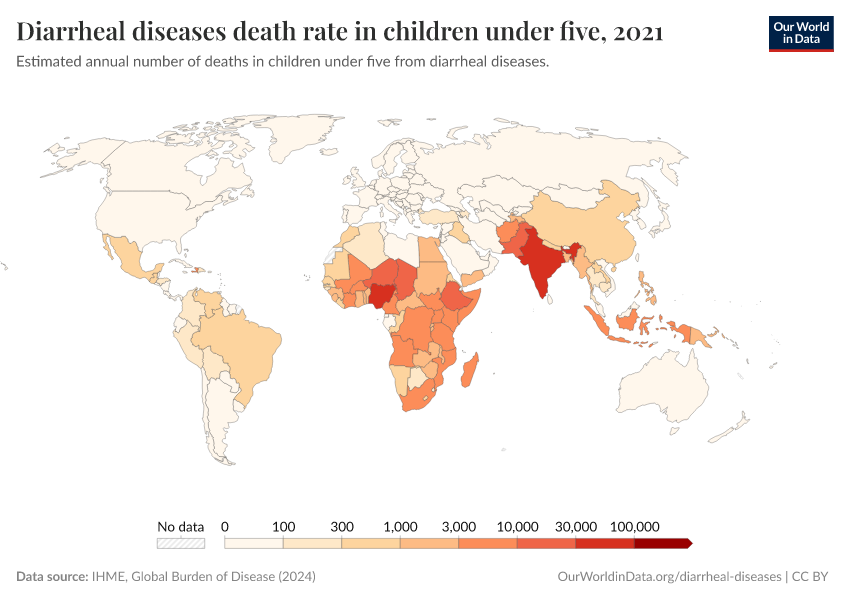

Around 390,000 of these deaths were among children and adolescents.

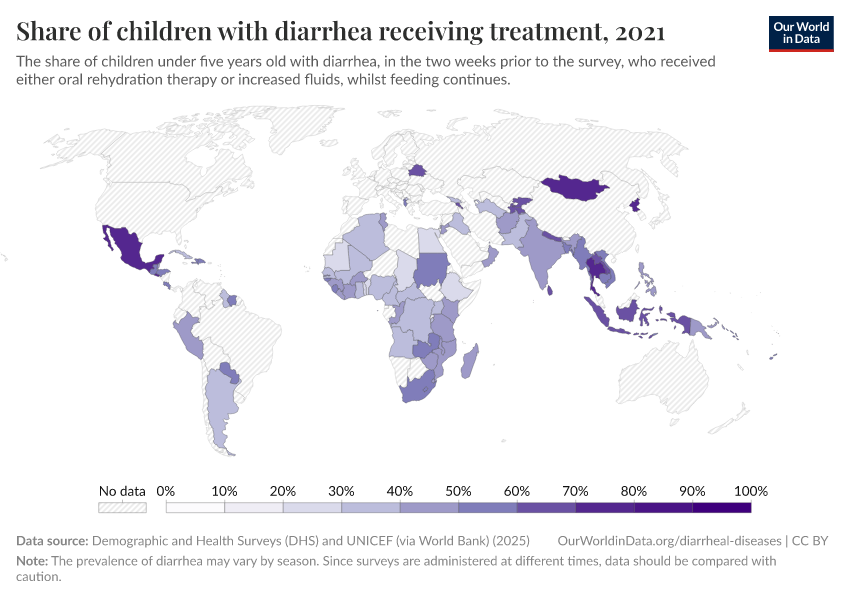

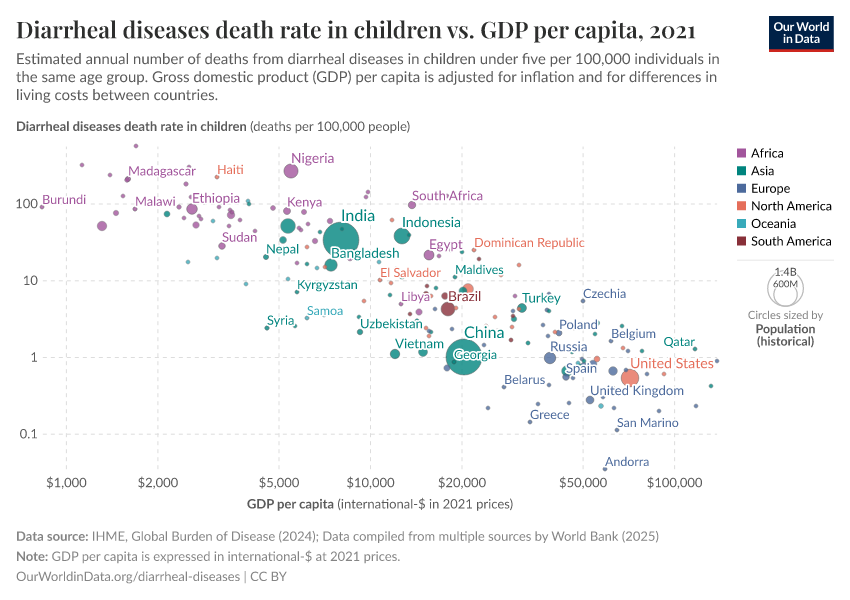

In recent decades, deaths from diarrheal diseases have fallen significantly across the world as a result of public health interventions. But more progress is possible.

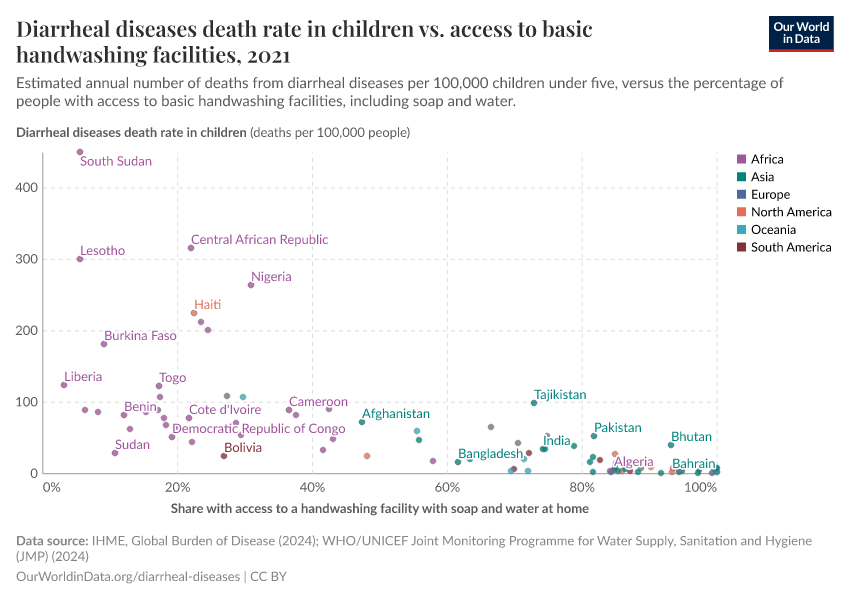

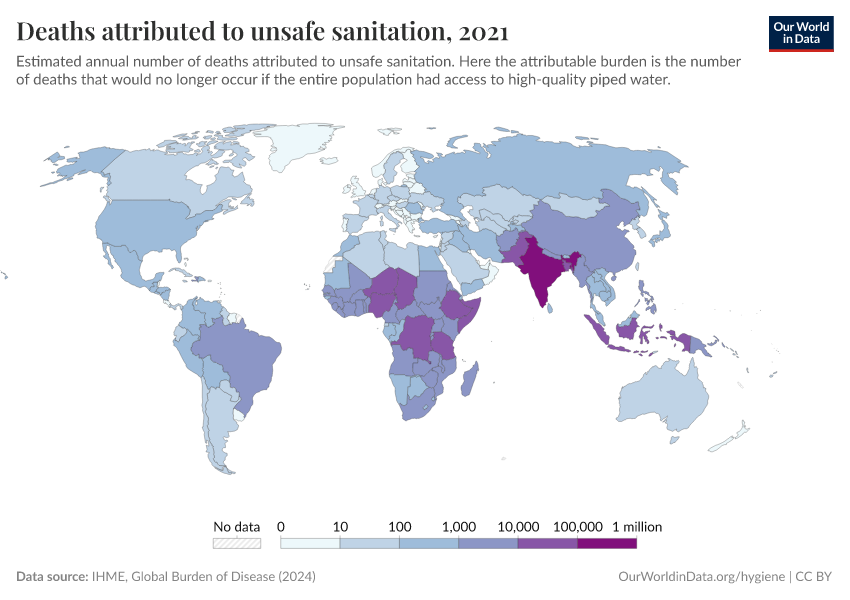

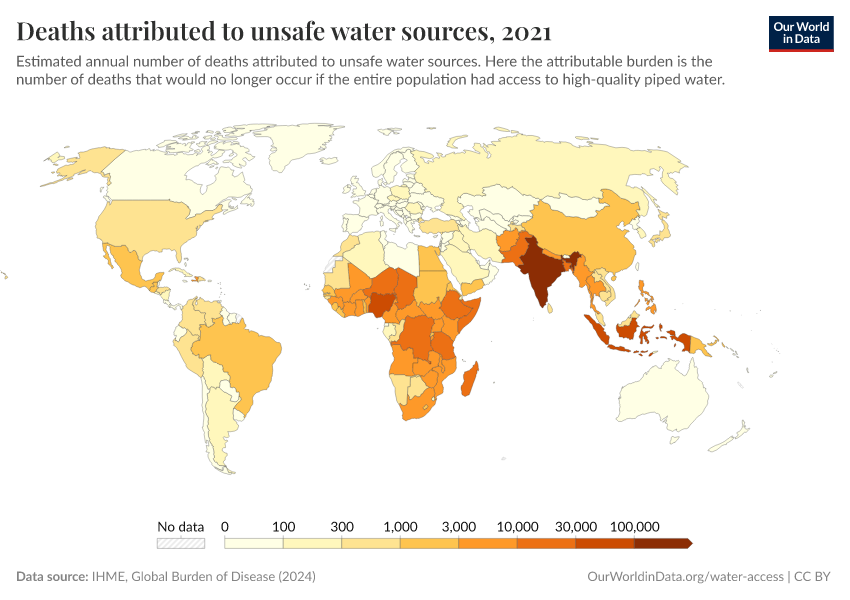

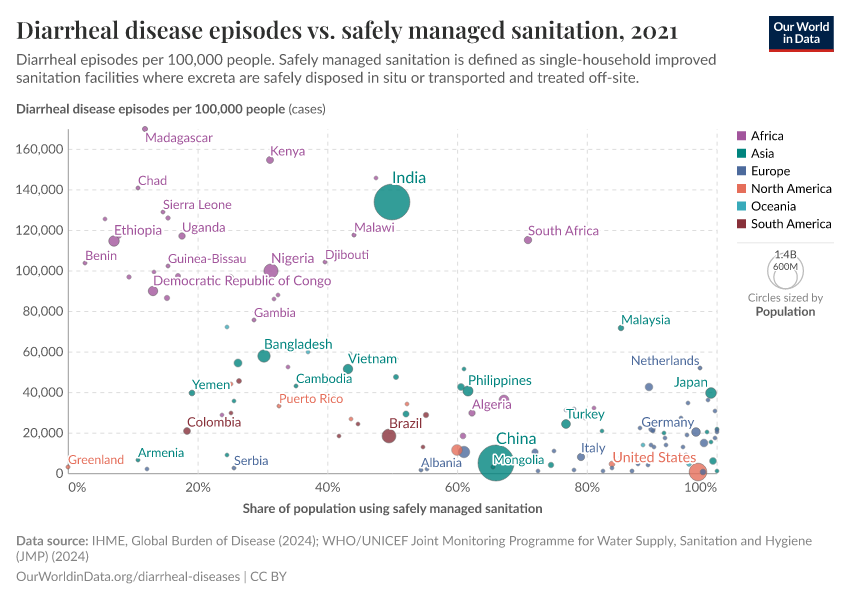

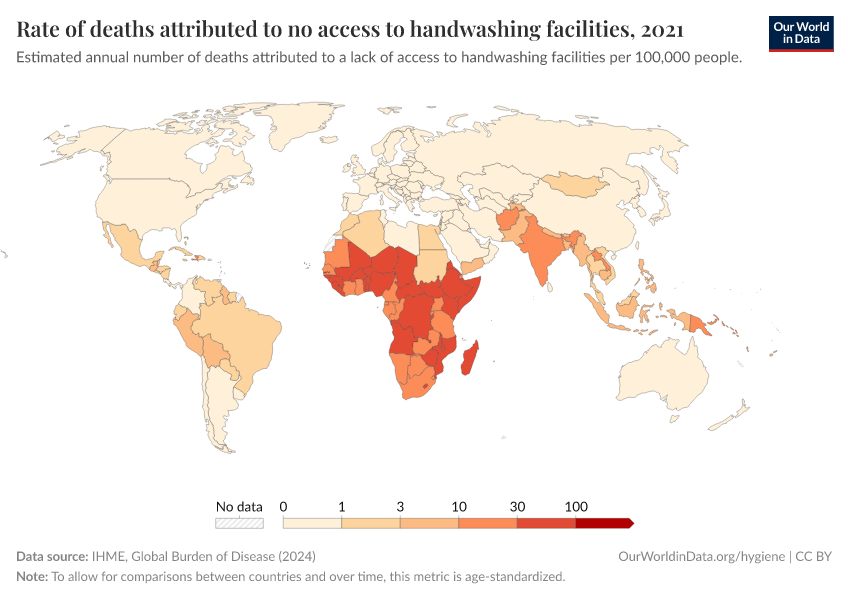

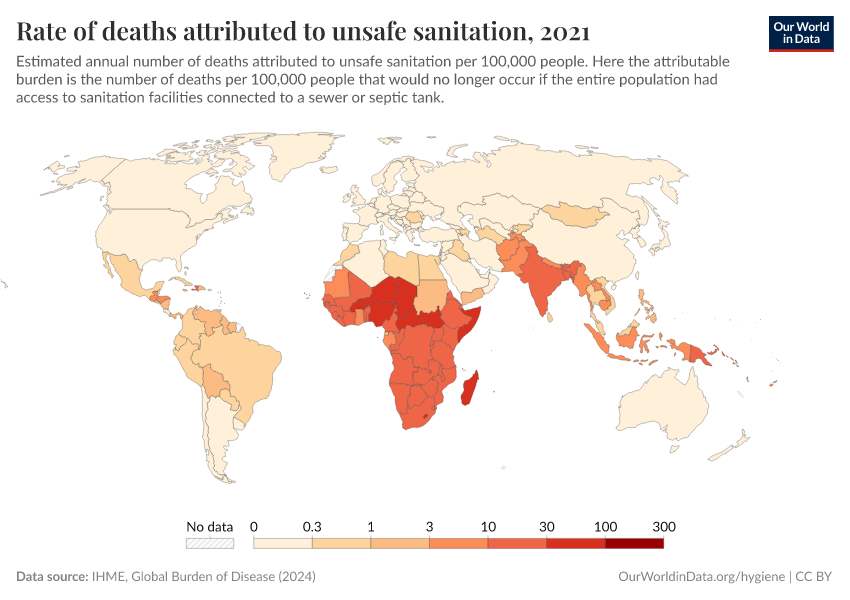

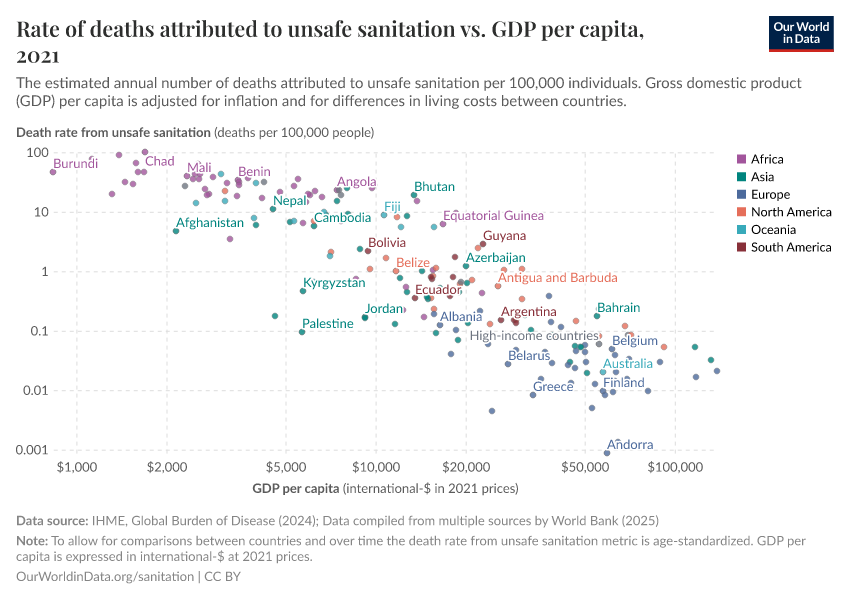

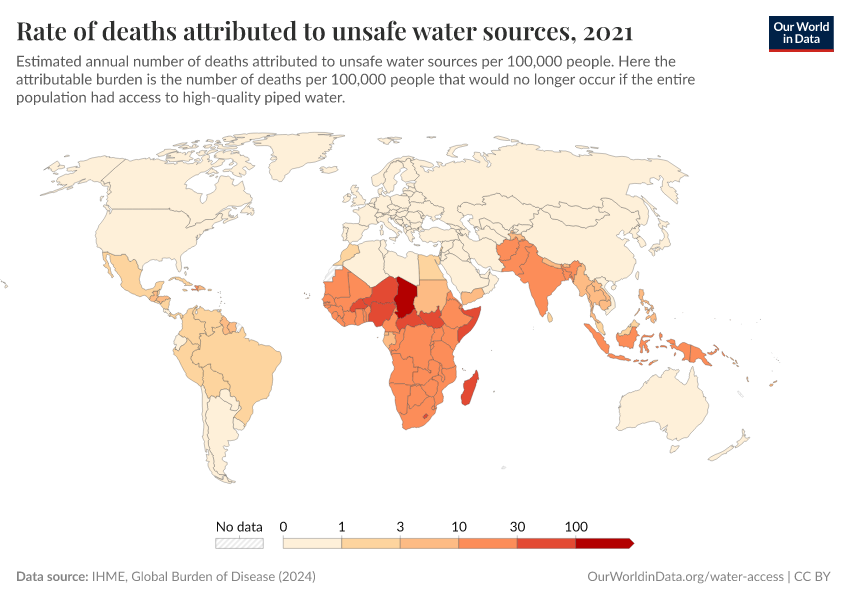

Diarrheal deaths are preventable because they are primarily caused by pathogens, whose spread can be easily controlled.

By increasing global access to clean water and sanitation, oral rehydration treatment, and vaccination, this major cause of death can be reduced substantially.

This page shows estimates of diarrheal death rates worldwide and the pathogens that cause them. We also offer data on access to public health measures and how they have changed.

Research & Writing

More articles on Diarrheal Diseases

Key Charts on Diarrheal Diseases

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

It’s estimated that 1.17 million people died from diarrheal diseases in 2021. Meanwhile, it’s estimated that around 746,000 died from suicide, around 397,000 died from homicide, and around 96,500 died in conflict and terrorism that year; these add up to 1.24 million. These estimates come from the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study, and you can explore the data here.

Protists are single-celled organisms that don’t fit into other categories, such as fungi, animals, or plants.

Webb, C., & Cabada, M. M. (2018). A Review on Prevention Interventions to Decrease Diarrheal Diseases’ Burden in Children. Current Tropical Medicine Reports, 5(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-018-0134-x

Cohen, A. L., Platts-Mills, J. A., Nakamura, T., Operario, D. J., Antoni, S., Mwenda, J. M., Weldegebriel, G., Rey-Benito, G., De Oliveira, L. H., Ortiz, C., Daniels, D. S., Videbaek, D., Singh, S., Njambe, E., Sharifuzzaman, M., Grabovac, V., Nyambat, B., Logronio, J., Armah, G., … Serhan, F. (2022). Aetiology and incidence of diarrhoea requiring hospitalisation in children under 5 years of age in 28 low-income and middle-income countries: Findings from the Global Pediatric Diarrhea Surveillance network. BMJ Global Health, 7(9), e009548. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009548 Deaths from cholera were primarily found in South Asia in this study.

Kremer, M., Luby, S. P., Maertens, R., Tan, B., & Więcek, W. (2023). Water Treatment And Child Mortality: A Meta-Analysis And Cost-effectiveness Analysis (No. w30835). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available here.

Santosham, M., Duggan, C. P., & Glass, R. (2019). Elimination of diarrheal mortality in children – the last half million. Journal of Global Health, 9(2), 020102. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.020102

Alsan, M., & Goldin, C. (2019). Watersheds in child mortality: The role of effective water and sewerage infrastructure, 1880–1920. Journal of Political Economy, 127(2), 586-638

Guerrant, R. L., Carneiro-Filho, B. A., & Dillingham, R. A. (2003). Cholera, Diarrhea, and Oral Rehydration Therapy: Triumph and Indictment. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 37(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1086/376619

Cutler, D., & Miller, G. (2005). The role of public health improvements in health advances: The twentieth-century United States. Demography, 42(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2005.0002

Van Poppel, F., & Van der Heijden, C. (1997). The effects of water supply on infant and childhood mortality: A review of historical evidence. Health Transition Review, 113–148. https://ocw.tudelft.nl/wp-content/uploads/Childhood-Mortality.pdf

Shulman, S. T. (2004). The History of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Pediatric Research, 55(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1203/01.PDR.0000101756.93542.09

These figures are the death rates among children under 2 years old.

Burström, B., Macassa, G., Öberg, L., Bernhardt, E., & Smedman, L. (2005). Equitable child health interventions: The impact of improved water and sanitation on inequalities in child mortality in Stockholm, 1878 to 1925. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 208–216. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1449154/

Macassa, G., Ponce de Leon, A., & Burström, B. (2006). The impact of water supply and sanitation on area differentials in the decline of diarrhoeal disease mortality among infants in Stockholm 1878—1925. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 34(5), 526–533. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2003.034900

Helgertz, J., & Önnerfors, M. (2019). Public water and sewerage investments and the urban mortality decline in Sweden 1875–1930. The History of the Family, 24(2), 307–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2018.1558411

Harris, J. B., LaRocque, R. C., Qadri, F., Ryan, E. T., & Calderwood, S. B. (2012). Cholera. The Lancet, 379(9835), 2466–2476. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X

Chan, C. H., Tuite, A. R., & Fisman, D. N. (2013). Historical Epidemiology of the Second Cholera Pandemic: Relevance to Present Day Disease Dynamics. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e72498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072498

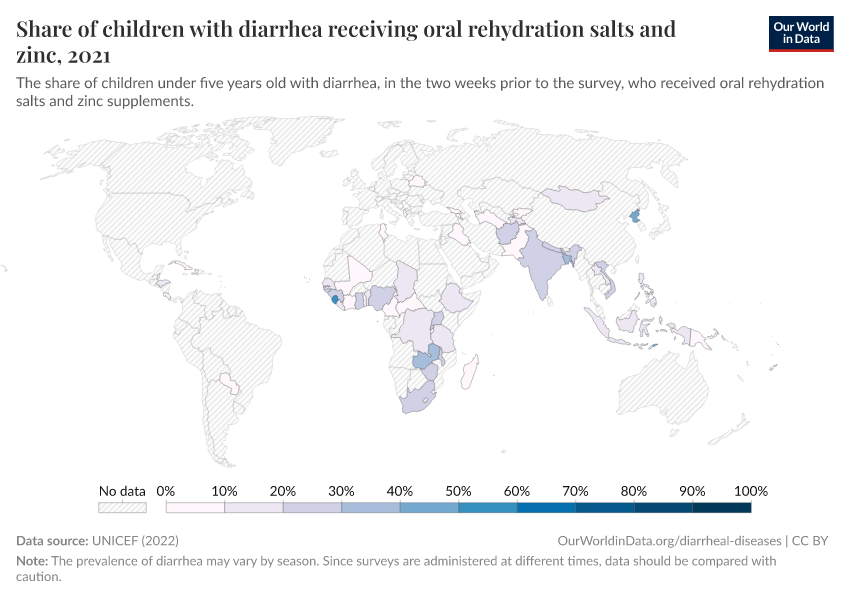

Oral rehydration solution effectively replaces fluid loss in many diarrheal diseases, not just cholera.

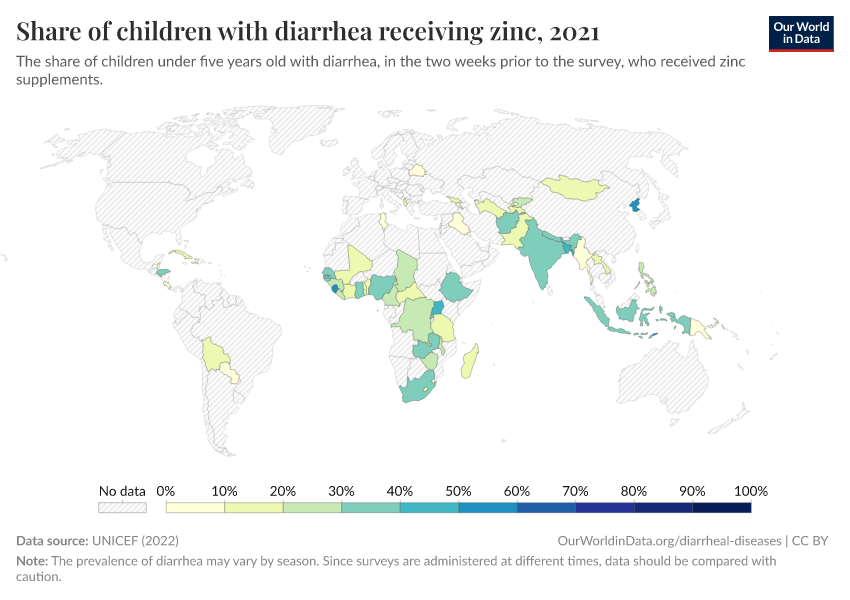

Zinc supplementation also reduces diarrheal diseases and can be provided with oral rehydration solution.

Additional medications, such as antibiotics and antiparasitic treatments, may also be needed to treat some diarrheal diseases.

Zinc Supplementation in Acute Diarrhea is Acceptable, Does Not Interfere with Oral Rehydration, and Reduces the Use of Other Medications: A Randomized Trial in Five Countries. (2006). Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, 42(3), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mpg.0000189340.00516.30

Santosham, M., Chandran, A., Fitzwater, S., Fischer-Walker, C., Baqui, A. H., & Black, R. (2010). Progress and barriers for the control of diarrhoeal disease. The Lancet, 376(9734), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60356-X

Black, R. E. (2019). Progress in the use of ORS and zinc for the treatment of childhood diarrhea. Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 010101. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.010101

Patel, A., Mamtani, M., Dibley, M. J., Badhoniya, N., & Kulkarni, H. (2010). Therapeutic Value of Zinc Supplementation in Acute and Persistent Diarrhea: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE, 5(4), e10386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010386

Kanungo, S., Azman, A. S., Ramamurthy, T., Deen, J., & Dutta, S. (2022). Cholera. The Lancet, 399(10333), 1429–1440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00330-0

Deen, J., Mengel, M. A., & Clemens, J. D. (2020). Epidemiology of cholera. Vaccine, 38, A31–A40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.078

Santosham, M., Duggan, C. P., & Glass, R. (2019). Elimination of diarrheal mortality in children – the last half million. Journal of Global Health, 9(2), 020102. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.020102

Bhattacharya, S. K. (1994). History of development of oral rehydration therapy. Indian Journal of Public Health, 38(2), 39–43. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7530695/

Binder, H. J., Brown, I., Ramakrishna, B. S., & Young, G. P. (2014). Oral Rehydration Therapy in the Second Decade of the Twenty-first Century. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 16(3), 376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-014-0376-2

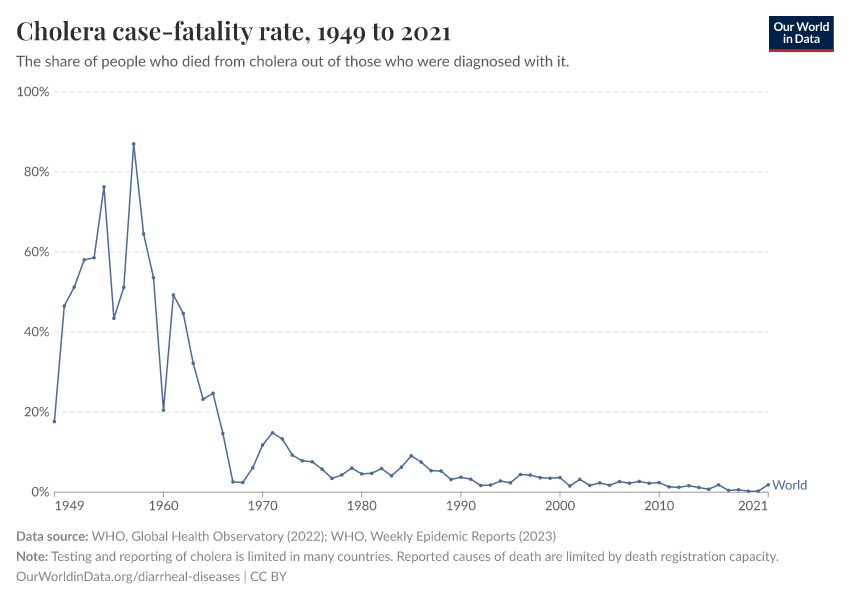

The case-fatality rate of cholera now ranges between 0 to 10% globally. However, this figure has limitations: many countries lack surveillance and reporting of cholera cases. Furthermore, some countries use different definitions of cases due to a lack of testing capacity. For example, some countries describe all cases of watery diarrhea as cholera cases during outbreaks due to limited laboratory capacity.

The case-fatality rate has also risen during large outbreaks from conflict and natural disasters, when people may lack access to clean water, sanitation, and treatments.

Ganesan, D., Gupta, S. S., & Legros, D. (2020). Cholera surveillance and estimation of burden of cholera. Vaccine, 38, A13–A17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.036

Wiens, K. E., Xu, H., Zou, K., Mwaba, J., Lessler, J., Malembaka, E. B., Demby, M. N., Bwire, G., Qadri, F., Lee, E. C., & Azman, A. S. (2022). Towards estimating true cholera burden: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Vibrio cholerae positivity [Preprint]. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.05.22280736

Ezezika, O., Ragunathan, A., El-Bakri, Y., & Barrett, K. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to implementation of oral rehydration therapy in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0249638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249638

Santosham, M., Chandran, A., Fitzwater, S., Fischer-Walker, C., Baqui, A. H., & Black, R. (2010). Progress and barriers for the control of diarrhoeal disease. The Lancet, 376(9734), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60356-X

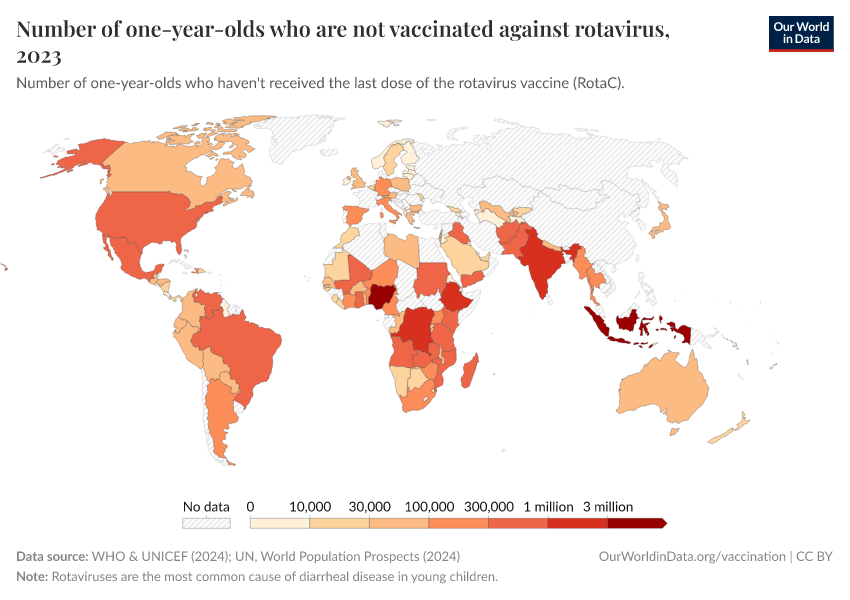

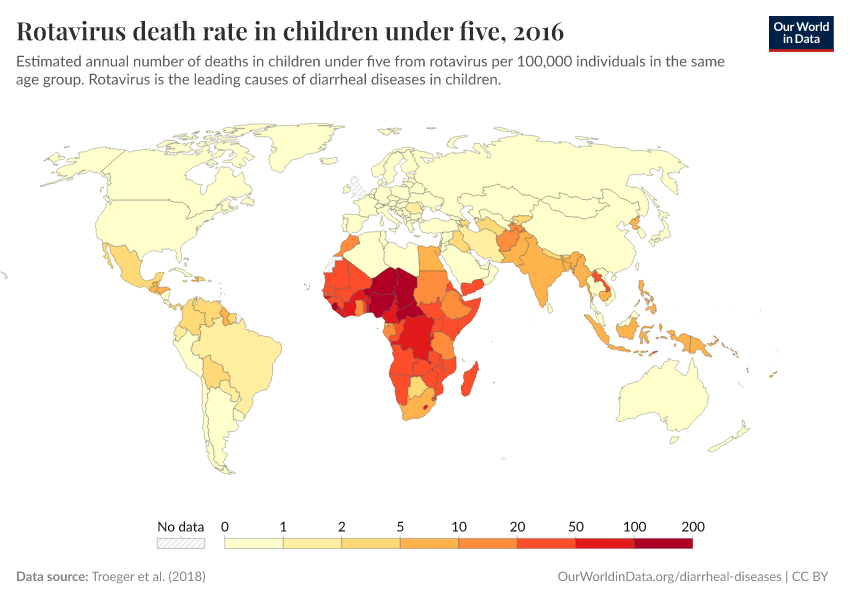

The effectiveness of rotavirus vaccines has been around 86% among children under 12 months in countries with low rotavirus mortality, and 63 or 66% in countries with high rotavirus mortality.

Burnett, E., Parashar, U. D., & Tate, J. E. (2020). Real-world effectiveness of rotavirus vaccines, 2006–19: A literature review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 8(9), e1195–e1202. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30262-X/fulltext

The reasons for a lower efficacy in poorer countries are unknown but may result from many factors. For example, other oral vaccines, including vaccines against polio and cholera, have also shown lower efficacies in poorer countries. This may be because children have co-infections with other enteric viruses, which reduce their gut immune response to the vaccines. Other potential factors include higher exposure to the virus and variations in gut microbiomes, blood groups, and immune antigens.

Burke, R. M., Tate, J. E., Kirkwood, C. D., Steele, A. D., & Parashar, U. D. (2019). Current and new rotavirus vaccines: Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 32(5), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0000000000000572

Burnett, E., Parashar, U., & Tate, J. (2018). Rotavirus Vaccines: Effectiveness, Safety, and Future Directions. Pediatric Drugs, 20(3), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-018-0283-3

Kirkwood, C. D., Ma, L.-F., Carey, M. E., & Steele, A. D. (2019). The rotavirus vaccine development pipeline. Vaccine, 37(50), 7328–7335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.076

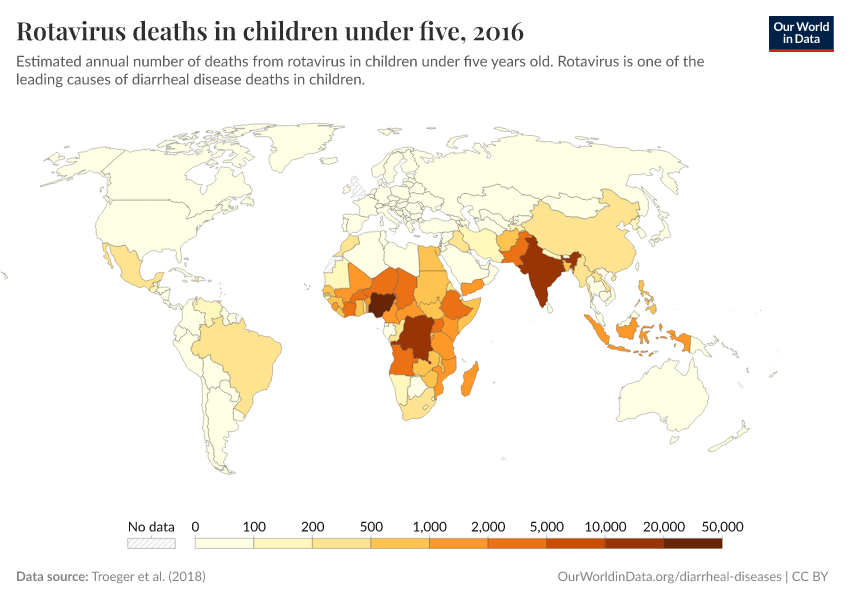

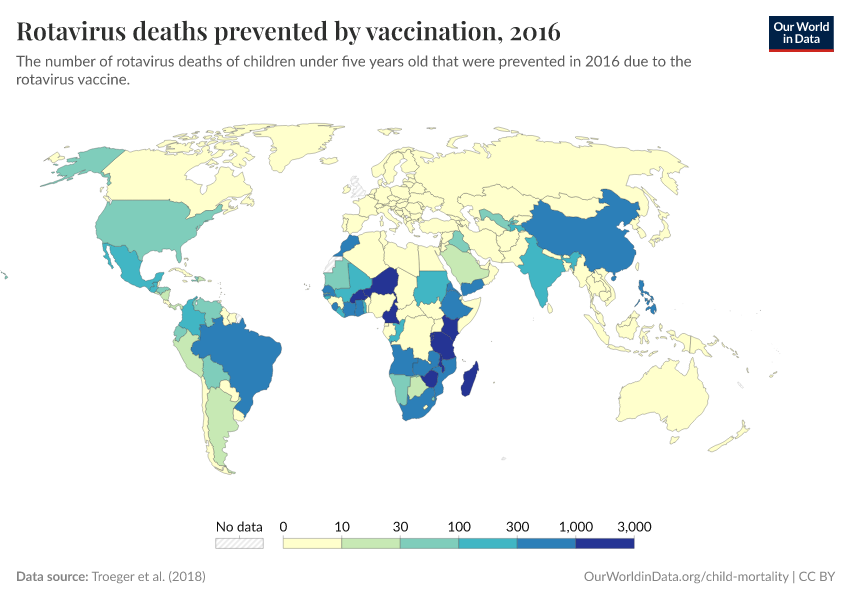

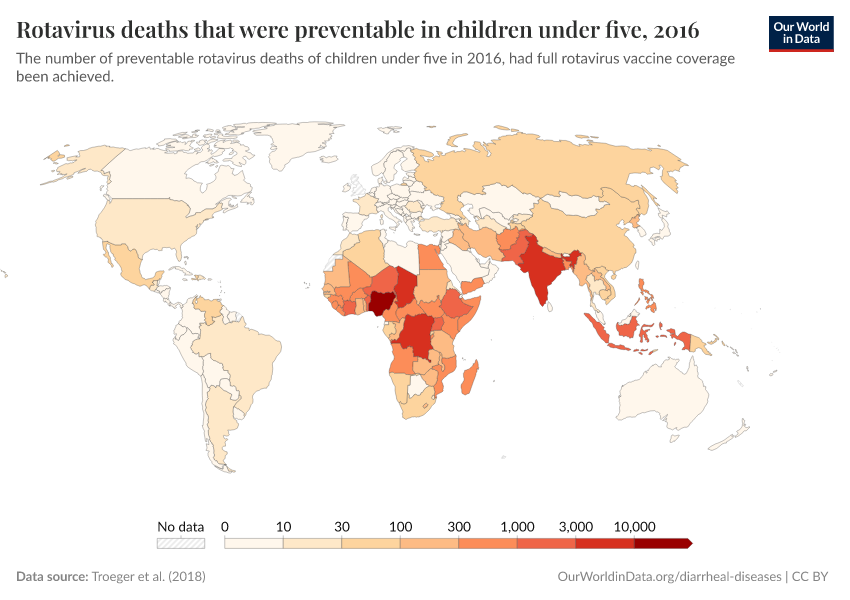

Troeger, C., Khalil, I. A., Rao, P. C., Cao, S., Blacker, B. F., Ahmed, T., Armah, G., Bines, J. E., Brewer, T. G., Colombara, D. V., Kang, G., Kirkpatrick, B. D., Kirkwood, C. D., Mwenda, J. M., Parashar, U. D., Petri, W. A., Riddle, M. S., Steele, A. D., Thompson, R. L., … Reiner, R. C. (2018). Rotavirus Vaccination and the Global Burden of Rotavirus Diarrhea Among Children Younger Than 5 Years. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(10), 958. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1960

The authors estimate that the rotavirus averted around 28,000 deaths in children under five in 2016. They also estimate that an additional 83,200 deaths in this age group could have been averted if full vaccine coverage had been achieved that year.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani, Fiona Spooner, Hannah Ritchie, and Max Roser (2023) - “Diarrheal Diseases” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/diarrheal-diseases' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-diarrheal-diseases,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner and Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser},

title = {Diarrheal Diseases},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/diarrheal-diseases}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.