Eradication of Diseases

Which diseases could we eradicate in our lifetimes and how?

This article was first published in June 2014 and we updated the text in January 2024.

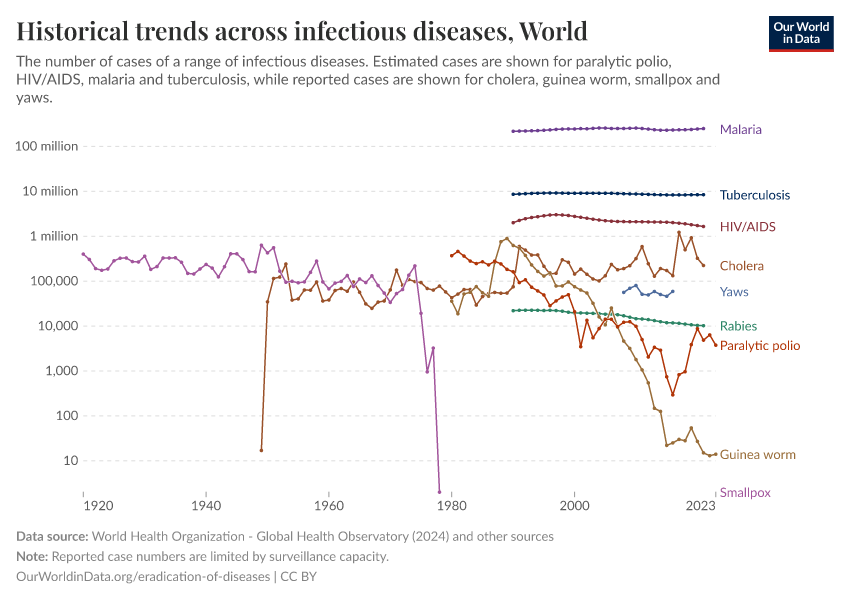

The ultimate goal in the fight against diseases is their eradication. In theory, many diseases could be eradicated. In practice, only a handful of diseases meet the criteria that make them eradicable with current knowledge, institutions, and technology.

In this topic page, we look at the progress the world has made in eradicating diseases, what makes a disease eradicable, and which diseases we can hope to eradicate in the future.

See all interactive charts on Eradication of Diseases ↓

Related topics:

Other research and writing on the eradication of diseases on Our World in Data:

- Smallpox is the only human disease to be eradicated — here's how the world achieved it

- How rinderpest was eradicated

- Guinea worm disease is close to being eradicated — how was this progress achieved?

- Malaria was common across half the world — since then it has been eliminated in many regions

- We need more testing to eradicate polio worldwide

“Eradication” versus “Elimination”

The eradication of a disease is a global and permanent achievement, while the elimination of a disease relates to a specific geographic area.1

Eradication means that intervention measures are no longer required, and the agent that previously caused the disease is no longer present.

In contrast, the elimination of a disease is when deliberate effort leads to local infections being reduced to zero within a defined geographic area. A disease can be eliminated from a specific region without being eradicated globally. Additionally, actions to prevent the disease from transmitting or re-emerging are still required once a disease is eliminated.1

Disease eradication is an ongoing process

So far, the world has eradicated two diseases — smallpox and rinderpest. How many other diseases could we eradicate?

On this topic page, we are primarily guided by the list of eradicable diseases provided by The International Task Force for Disease Eradication (ITFDE). ITFDE was formed in 1988 at The Carter Center; it is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and advises bodies such as the World Health Organisation on various aspects of disease eradication.2

The table here shows the two diseases that the world has eradicated and the seven diseases that ITFDE has listed as potentially eradicable.3 These diseases are polio, Guinea worm disease, lymphatic filariasis, cysticercosis, measles, mumps, and rubella. These diseases are considered eradicable diseases because they satisfy the criteria for disease eradication discussed below on this topic page.

Which diseases can be eradicated, and when they can be eradicated, is a topic of ongoing discussion. The following examples illustrate the point:

While ITFDE has placed seven diseases on its eradicable diseases list, the WHO currently suggests that polio and Guinea worm disease are eradicable, while lymphatic filariasis, cysticercosis, measles, mumps, and rubella could be eliminated from some parts of the world.

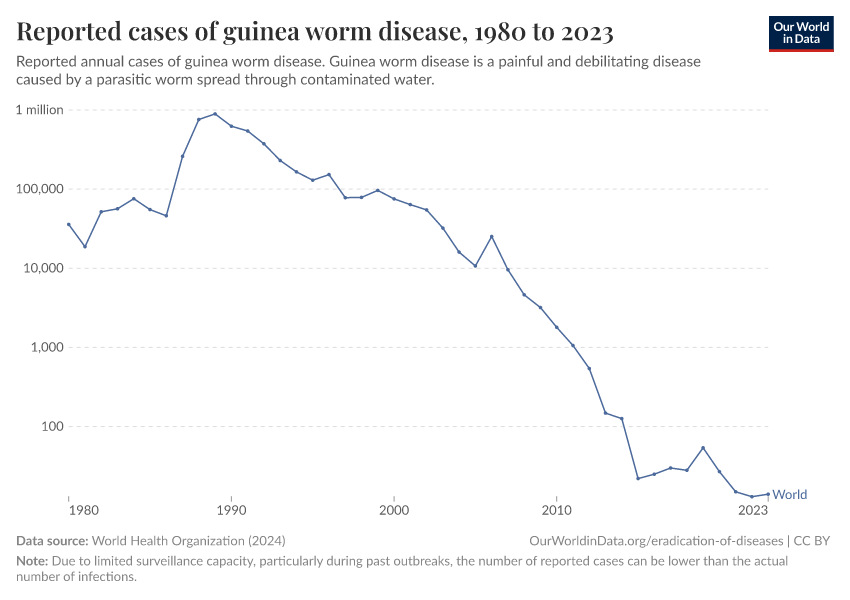

Even for diseases where the possibility of eradication has been agreed upon, the target date may evolve. The timeline for Guinea worm disease eradication was first set for 1991, then moved to 2009, then 2015, then 2020, and is currently set for 2030.4

The Global Malaria Eradication Program was established in 1955 to eradicate malaria, but it was abandoned in 1969. Since then, however, a renewed focus on malaria eradication has emerged, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has proposed a plan to end malaria by 2040.5

All these examples illustrate that disease eradication is an ongoing process. As science discovers new facts about diseases and researchers invent new ways to tackle them, the world may change its perspective on which goals are feasible now and which ones are not yet.

Infectious diseases that have been eradicated and could be eradicated in the future.

Disease | Cause | Ways to eradicate |

|---|---|---|

Smallpox | Variola virus | Declared eradicated in 1980, using vaccination |

Rinderpest | Rinderpest virus | Declared eradicated in 2011, using sanitary measures and vaccination |

Poliomyelitis | Poliovirus | Vaccination |

Guinea worm disease | Parasitic worm Dracunculus medinensis | Hygiene, water decontamination, and health education |

Measles | Measles morbillivirus | Vaccination |

Mumps | Mumps orthorubulavirus | Vaccination |

Rubella | Rubella virus | Vaccination |

Lymphatic filariasis | Roundworms: W. bancrofti, B. malayi, B. timori | Preventive chemotherapy |

Cysticercosis | Tapeworms: T. solium, T. saginata, T. asiatica | Sanitation and health education. Vaccination of pigs |

What makes a disease eradicable?

Louis Pasteur once said that “it is within the power of man to eradicate infection from the earth”.6 That power has so far eradicated two infectious diseases: smallpox and rinderpest.

We are also getting closer to eradicating polio and Guinea worm disease. But can we eradicate all infections from the world?

For a disease eradication to be feasible and an option worth considering it needs to meet certain criteria. Below we highlight some of these criteria.

Notably, these criteria are not set in stone. Eradication of diseases is an ongoing process, and as we learn more about diseases and find new ways to treat them, we may find that some of these criteria become obsolete or that diseases that were once considered not to fulfill any of these requirements begin to tick all the boxes.

Key requirements for disease eradication

There are several required aspects of a disease that need to be fulfilled for a disease to be considered eradicable:

- It needs to be an infectious disease

- We need to have ways to either prevent or treat the infection

For a disease to be eradicable, it’s considered necessary to have an infectious cause whose spread could be halted with interventions.7 These interventions could be preventative measures, such as vaccination or water filtration, or treatments that get rid of the pathogen within a host and reduce its ability to spread further.

Disease aspects that make eradication more likely

In addition the the key requirements, many other aspects of the disease should be considered in the efforts to eradicate it:

- How many pathogens cause the disease?

- Does the disease-causing pathogen have one or more hosts?

- Are there any identifiable symptoms of the disease?

- Has regional disease elimination been proven possible?

- Is the perceived disease burden high and is financial and political support available?

How many pathogens cause the disease?

The more pathogens cause the disease, the more difficult it will be to eradicate. If a disease is caused by a small number of pathogens that are closely related, then often the same tools and approaches can be used in eradication efforts. For example, smallpox was caused by two types of variola virus, and the same vaccine was used to prevent both. Contrast this to a disease such as pneumonia, which is caused by multiple pathogens — bacteria and viruses – each of which requires a different treatment.

Does the disease-causing pathogen have one or more hosts?

Diseases with multiple hosts are difficult to target for eradication because they often require the disease to be eradicated in all of them.8

Pathogens that cause diseases such as poliomyelitis, measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, and whooping cough, all have a single host — humans.

But single-host pathogens are generally an exception rather than a rule. For example, the 2020 eradication target for Guinea worm disease had to be postponed because we learned about high rates of transmission of the Guinea worm between dog populations, which may be a source of new human infections.9

Are there any identifiable symptoms of the disease?

Some diseases are not easy to detect in the first place. Many worldwide live with latent tuberculosis infection today, which has no symptoms but can potentially reactivate and cause disease.10

For other diseases, even when symptoms may be visible or detectable, the stigma surrounding the disease may limit our ability to treat it. Hepatitis C is a disease that fits most eradication criteria — however, because the disease has a high prevalence among drug users, there is a stigma attached to being identified as an infected individual, making it difficult to identify all the cases.

Has regional disease elimination been achieved?

Disease eradication is usually achieved one step at a time. A proof-of-concept eradication in one region is a positive indicator that eradication at a larger scale is possible. Once the disease elimination has been achieved on a smaller scale, greater support for the feasibility of elimination elsewhere can be gathered.

Is the perceived disease burden high and is financial and political support available?

The perceived burden of a disease, the estimated cost of eradication, and the political stability of affected countries are further factors that determine the eradicability of diseases. Polio is a good example here. Polio eradication efforts illustrate the powerful impact of both a unified international effort and local political support.

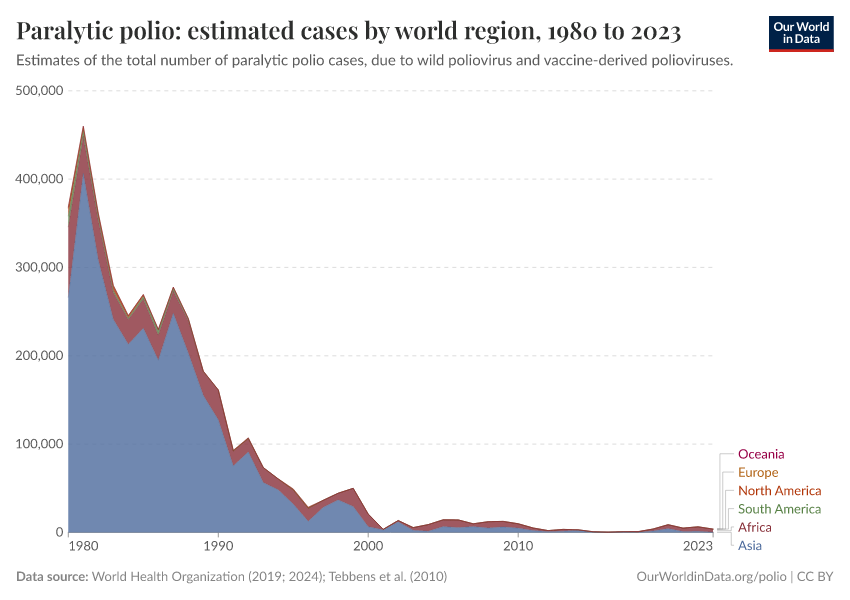

In 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was set up to provide large-scale continued support for the eradication of polio. Since then, the number of paralytic polio cases has been greatly reduced such that in recent years it is endemic in only a few countries.

But polio also illustrates that positive developments might reverse. Nigeria’s case numbers surged in the early 2000s because of rumors that polio vaccination was used to cause infertility and spread HIV in the local communities, which led to an 11-month vaccination boycott.11 This example illustrates that eradication efforts have to span from international to national and community levels to be successful.

What are the benefits of eradicating diseases?

The immediate benefit of eradicating a disease is obvious — preventing suffering and saving people’s lives.

But eradicating a disease can also have significant economic benefits. Disease eradication takes years to achieve and can require a lot of financial investment.

But, as the chart below illustrates, while the initial costs of disease eradication efforts are high, in the long term these costs can pay off. Simply controlling a disease can be more expensive because the disease may pose a continuous burden on healthcare systems and reduce productivity from the sick population.

How much we should spend on eradicating a disease? There will always be other good causes we can spend money on. These include non-health causes, health causes with greater burden, eradication of different diseases, and even research into more cost-effective treatments instead of eradication. The scenario or intervention which brings the highest benefit needs to be assessed for each disease separately.

As a classical paper by Walter R. Dowdle’s classical paper on disease eradication states: “Elimination and eradication are the ultimate goals of public health. The only question is whether these goals are to be achieved in the present or [by] some future generation."12

Successfully eradicated diseases

The world has successfully eradicated two diseases:

- Smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980

- Rinderpest was declared eradicated in 2011

Smallpox: 200 years between a vaccine and disease eradication

The last recorded case of smallpox occurred in 1977 in Somalia. The disease was officially declared eradicated by the World Health Organization in 1980.

From the invention of a vaccine against smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1796, it took almost two centuries to eradicate the disease.

It was only with the establishment of the World Health Organization in the aftermath of World War II that international quality standards for the production of smallpox vaccines were introduced and the fight against smallpox moved from a national to an international agenda.

In 1966, the WHO launched the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Program. By then, smallpox had been eliminated in various countries in Europe, the Americas, and the Soviet Union, but large parts of Asia and Africa still struggled under smallpox’s disease burden.

The world map illustrates the decade when smallpox was no longer endemic in a country.13

Rinderpest: eradication began before a vaccine against the disease was available

Rinderpest is the only animal disease that has been eradicated so far.

Rinderpest outbreaks in cattle used to cause devastating losses for animal farmers. The eradication efforts began in the 1920s – before the vaccine against the rinderpest virus was even available. Measures such as animal quarantine and slaughter were used to contain the disease.

The map here shows the last year in which cases of rinderpest were reported in a country. In 1960 an English veterinary scientist Walter Plowright developed a vaccine against rinderpest, which finally led to its eradication.

Diseases we could eradicate

Polio

Polio, short for poliomyelitis, is a disease that is caused by the poliovirus. Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin invented two polio vaccines in 1953 and 1961, respectively, which eliminated polio from the United States and Canada in 1979 and rapidly led to a large reduction of the disease in Western Europe.

While Salk's vaccine required injection with a needle, Sabin's vaccine is oral and can be swallowed. The latter feature made its distribution throughout the developing world possible, as fewer trained healthcare staff were required for its administration.

There are three serotypes of wild poliovirus, and two have been eradicated. The last case of wild poliovirus serotype 2 was seen in 1999 in India, while the last case of wild poliovirus serotype 3 was seen in 2012 in Nigeria. They were declared globally eradicated by the WHO in 2015 and 2019 respectively.

The map below highlights the last decade in which cases of wild poliovirus were reported in a country — it does not include vaccine-derived poliovirus cases.

Guinea worm disease

Guinea worm disease, also known as dracunculiasis, is a disease caused by the Dracunculus medinensis worm.

There is no vaccine against the disease, however, it can be successfully eliminated by clean water treatment, public education, and the identification and treatment of people with the disease.

The map below shows the decade when each country was certified free of guinea worm disease, and which countries are still endemic for the disease.

Lymphatic filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis is a disease caused by roundworms. It is not fatal but is highly debilitating. It causes the swelling of lymph nodes, which in turn can cause painful swelling of the arms, legs, and other parts of the body.

The majority of cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, as you can see in the map below.

While the lymphatic filariasis-causing roundworms are transmitted by mosquitoes, the transmission can be effectively stopped by preventive chemotherapy. The WHO and its partners have been working on mass drug administration campaigns (MDAs) to stop the transmission of the diseases. Rather than targeting just the infected individuals, MDAs target groups of people living in endemic areas.14

Measles, mumps, and rubella

Measles, mumps and rubella are three viral diseases that can be prevented by child vaccination.

The only known hosts of these viruses are humans, which makes them good targets for eradication. One of the major obstacles to eradicating these diseases is the misperception of the seriousness of the disease in the public, which leads to insufficient vaccination rates. In addition, information on the disease prevalence in developing countries is also insufficient or lacking.

Measles is a highly contagious killer of young children globally, even though a safe and effective vaccine is available.

Mumps infection occurs via direct human contact or by airborne droplets. It causes painful swelling at the side of the face under the ears (the parotid glands), fever, headache, and muscle aches. It can cause sterility in teenagers and adults.

Rubella is usually mild in children, but infections during pregnancy carry a serious risk of long-term complications, such as deafness, cataracts, heart defects, or lead to fetal death.15

The chart here shows the number of infants vaccinated against measles and rubella, versus the total number of infants.

Cysticercosis

Cysticercosis is a parasitic tissue infection of tissues (including brain and muscle tissue) caused by larval cysts of the pork tapeworm (Taenia solium). In low-income countries, these infections are a major cause of adult-onset seizures. More information on the disease can be found on the website of the CDC here.

The International Task Force for Disease Eradication put cysticercosis on a list of eradicable diseases back in 1993. However, the disease still affects millions of people globally.

The disease is caused by tapeworms, which can affect the nervous system and cause severe epileptic seizures.

The map below shows the estimated rate of prevalence of cysticercosis. As is shown, the disease is most prevalent in Mexico, Central and South America, South Asia, and southern Africa.

Eradication of cysticercosis in humans relies on the ability to break the tapeworm transmission cycle between humans and pigs. This can be done effectively through sanitary measures and proper inspection and cooking of pork. Furthermore, vaccines against the tapeworm are available for use in pigs, and the drug oxfendazole can be used to remove the tapeworm from animals.16

Diseases that could be eliminated in some parts of the world

The process of disease eradication is ongoing. As new treatments become available and as we start to better understand the disease ecology, new avenues open for the eradication of diseases.

There is no one defined path for disease eradication. Eradication is usually the final goal, and control of disease spread or local disease elimination is a closer goal for most diseases.

On the list of diseases that could potentially be eliminated in parts of the world are yaws, malaria, and trachoma.

Yaws

Yaws is a disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. It is a chronic infectious disease that can be disfiguring and debilitating.

It primarily affects the skin, bones, and connective tissue: patients develop highly contagious skin lumps, ulcers, and bone deformities, and the disease spreads through direct contact with the wounds of an infected person.

The infection can be effectively treated with antibiotics, such as azithromycin or benzathine penicillin.

The prevalence of the disease is not known, due to limited testing and reporting worldwide. However, the map below visualizes which countries are endemic for the disease.

Trachoma

Trachoma is a disease caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. The disease affects the eyes and causes blindness.

The map shows the estimated global prevalence of trachoma. Limited information is available on the surveillance of the disease, and estimates come with significant uncertainty.17

Trachoma can be prevented by sanitary measures such as access to clean water and facial hygiene. Mass administration of antibiotics can successfully stop disease transmission and surgery can reverse blindness caused by the disease.

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis, also called river blindness, is an eye infection caused by a parasitic worm. The disease can lead to blindness, skin damage, and epilepsy.

The map below shows the estimated prevalence of onchocerciasis worldwide. Limited information is available on the surveillance of the disease, and estimates come with significant uncertainty.

Recent evidence suggests that mass drug administration significantly reduces disease transmission.18

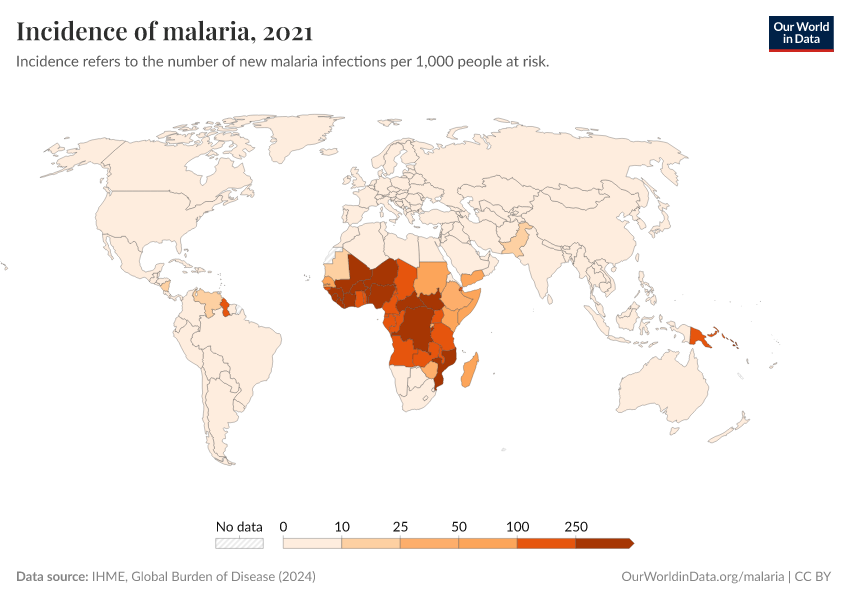

Malaria

Malaria has been eliminated in many countries in the world and was targeted for global eradication through the Global Malaria Eradication Programme, which began in 1955. However, the program was abandoned in 1969, due to feasibility and reduced funding.19

Since then, additional treatments and new vaccines have become available, and the prevalence of malaria has fallen.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation proposed a plan to end malaria by 2040.5 The eradication plan largely relies on developing new ways to prevent and treat the disease, such as effective vaccines, longer-lasting bed nets, and parasite resistance management programs.20

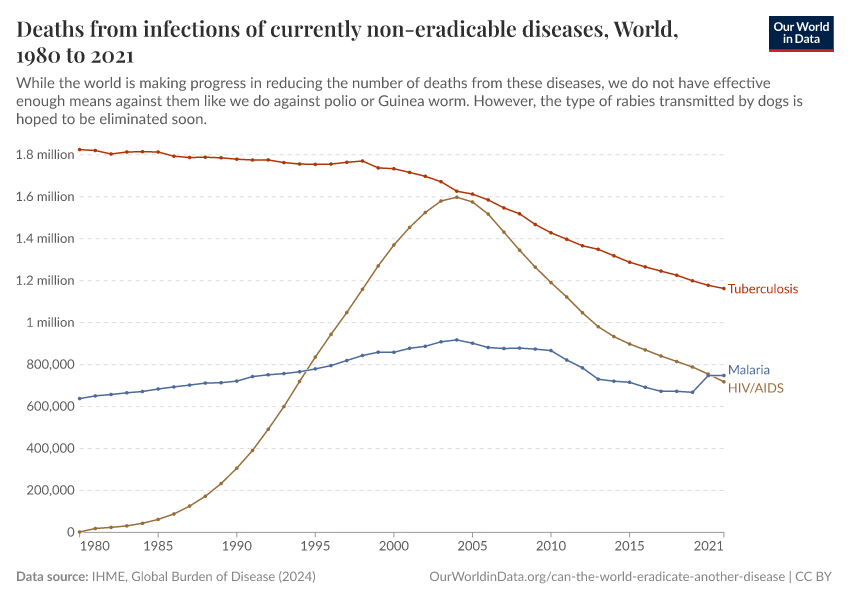

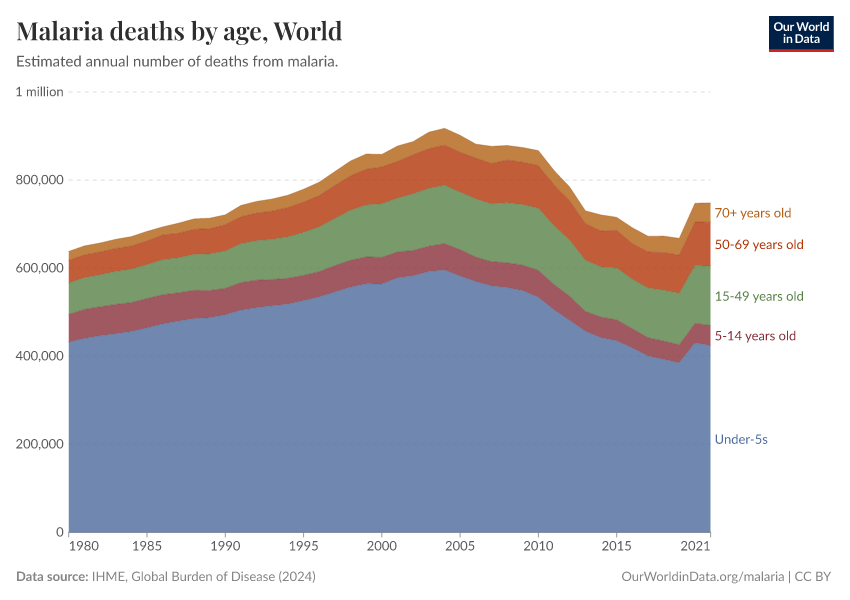

In the chart below, you can see the estimated number of annual deaths from malaria worldwide.

Key Charts on Eradication of Diseases

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

Dowdle, WR. (1999) The principles of disease elimination and eradication. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1998;76 (Suppl 2):22-25. Online here.

Recommendations of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication (2008).

The, Lancet. "Guinea worm disease eradication: a moving target."Lancet (London, England) 393.10178 (2019): 1261.

Dubos, René Jules, and Jean Dubos. The white plague: tuberculosis, man, and society. p228. Rutgers University Press, 1987.

There are also certain metabolic diseases that could be cured in all humans provided sufficient nutrition. These are mainly vitamin or essential element deficiencies such as scurvy (lack of vitamin C) or ion deficiency disorders. However, while it is theoretically possible that no human in the world would have one of these metabolic diseases at some point in time, these diseases will never be eradicated because they will return if a person's nutritional status changes.

However, rinderpest — one of the two eradicated diseases – had multiple animal hosts.

Eberhard, M. L., Ruiz-Tiben, E., Hopkins, D. R., Farrell, C., Toe, F., Weiss, A., … & Hance, Z. (2014). The peculiar epidemiology of dracunculiasis in Chad. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 90(1), 61-70.

World Health Organization (2019). "Global tuberculosis report 2019"

Larson, H., & Ghinai, I. (2011). Lessons from polio eradication. Nature, 473(7348), 446-447.

Dowdle, WR. (1999) The principles of disease elimination and eradication. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1998;76(Suppl 2):22-25.

A disease is no longer endemic when local circulation is no longer occurring, but there could still have been some cases imported from another country that were limited.

Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: progress report, 2017

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Pregnancy and Rubella. Available online.

Thompson, K. M., Simons, E. A., Badizadegan, K., Reef, S. E., & Cooper, L. Z. (2016). Characterization of the Risks of Adverse Outcomes Following Rubella Infection in Pregnancy. Risk Analysis, 36(7), 1315–1331. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12264

Maurice, J. (2014). Of pigs and people—WHO prepares to battle cysticercosis. The Lancet, 384(9943), 571-572.

See the WHO information on trachoma here: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trachoma

Hill, E., Hall, J., Letourneau, I. D., Donkers, K., Shirude, S., Pigott, D. M., ... & Cromwell, E. A. (2019). A database of geopositioned onchocerciasis prevalence data. data, 6(1), 67.

Cohen, J. M., Smith, D. L., Cotter, C., Ward, A., Yamey, G., Sabot, O. J., & Moonen, B. (2012). Malaria resurgence: A systematic review and assessment of its causes. Malaria Journal, 11(1), 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-122

Feachem, R. G., Chen, I., Akbari, O., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Bhatt, S., Binka, F., ... & Eapen, A. (2019). Malaria eradication within a generation: ambitious, achievable, and necessary. The Lancet, 394(10203), 1056-1112.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Max Roser, Sophie Ochmann, Hannah Behrens, Hannah Ritchie, and Bernadeta Dadonaite (2018) - “Eradication of Diseases” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/eradication-of-diseases' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-eradication-of-diseases,

author = {Max Roser and Sophie Ochmann and Hannah Behrens and Hannah Ritchie and Bernadeta Dadonaite},

title = {Eradication of Diseases},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2018},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/eradication-of-diseases}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.