What is economic growth? And why is it so important?

The goods and services that we all need are not just there; they need to be produced. Growth means that their quality and quantity increase.

Good health, a place to live, access to education, nutrition, social connections, respect, peace, human rights, a healthy environment, and happiness. These are just some of the many aspects we care about in our lives.

At the heart of many of these aspects that we care about are needs for which we require particular goods and services. Think of those that are needed for the goals on the list above — the health services from nurses and doctors, the home you live in, or the teachers who provide education.

Poverty, prosperity, and growth are often measured in monetary terms, most commonly as people’s income. However, while monetary measures have some important advantages, they have the big disadvantage of being abstract. In the worst case, monetary measures — like GDP per capita — are so abstract that we forget what they are actually about: people’s access to goods and services.

The point of this text is to show why economic growth is important and how the abstract monetary measures tell us about the reality of people’s material living conditions around the world and throughout history:

- In the first part, I want to explain what economic growth is and why it is so difficult to measure.

- In the second part, I will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of several measures of growth, and you will find the latest data on several of these measures so that we can see what they tell us about how people’s material living conditions have changed.

What are these goods and services that I’m talking about?

Have a look around yourself right now. Many of the things you see are products that were produced by someone so that you can use them: the trousers you are wearing, the device you are reading this on, the electricity that powers it, the furniture around you, the toilet that is nearby, the sewage system it is connected to, the bus or car or bicycle you took to get where you are, the food you had this morning, the medications you will receive when you get sick, every window in your home, every shirt in your wardrobe, and every book on your shelf.

At some point in the past, many of these products were not available. The majority did not have access to the most basic goods and services they needed. A recent study on the history of global poverty estimates that just two centuries ago, roughly three-quarters of the world "could not afford a tiny space to live, food that would not induce malnutrition, and some minimum heating capacity.”1

Let’s look at the history of the last item on that list above: books.

A few centuries ago, the only way to produce a book was for a scribe to copy it word-for-word by hand. Book production was a slow process; it took a scribe about eight months of daily work to produce a single copy of the Bible.2

It was so laborious that only very few books were produced. The chart shows the estimates of historians.3

But then, in the 15th century, the goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg combined the idea of movable letters with the mechanism that he knew from the wine presses in his hometown. He developed the printing press. Gutenberg developed a new production technology, and it changed things dramatically. Instead of spending months to produce one book, a worker was now able to produce several books a day.

As the printing press spread across Europe, book production soared. Books, which were previously only available to a tiny elite, became available to more and more people.

This is one example of how growth is possible and what economic growth is: an increase in the production of goods and services that people produce for each other.

A list of goods and services that people produce for each other

Before we get to a more detailed definition of economic growth, it’s helpful to remind ourselves of the astonishingly wide range of goods and services that people produce. I think this is helpful because measures of economic output can easily become abstract. This abstraction means we easily lose the mental connection to the goods and services such measures actually talk about.

This list of goods and services isn’t meant as a definitive list, but it helped me to think about the relevance of poverty and growth:4

At home: Light in your home at night; the sewage system; a shower; vacuum cleaner; fridge; heating; air conditioning; electricity; windows; a toilet — even a flush toilet; soap; a balcony or a garden; running water; warm water; cutlery and dishes; a hut — or even a warm apartment or house; an oven; sewing machine; a stove (that doesn’t poison you); carpet; toilet paper; trash bags; music recordings or even online streaming of the world’s music and film; garbage collection; radio; television; a washing machine;5 furniture; telephone; a comfortable bed, and a room for one’s own.

Food: The most fundamental need is to have enough food. For much of human history, a large share of people suffered from hunger, and millions still do.

But we also need to have a richer and more varied diet to get all of the nutrients we need. Unfortunately, billions still suffer from micronutrient deficiency.

Also, think of clean drinking water; reliable markets and stores with a wide range of available goods; food that rarely poisons you (pasteurized milk, for example); spices; tea and coffee; kitchen utensils and practical ingredients (from a bag of flour to canned soups or a yogurt); chocolate and sweets; fresh fruit and vegetables; bread; take-away food or the possibility to go to a restaurant; ways to protect your food from spoiling (from the cold chain that delivers the goods to the cellophane to wrap it with); wine or beer; fertilizer (very important); and tractors to work the fields.

Knowledge: Education from primary up to university level; books; data that allows us to understand the world around us; newspapers; vocational training; kindergartens; and scientific knowledge to understand ourselves and the world around us.

Infrastructure: Public transportation with buses, subways, and trains; roads; paved roads; airplanes; bridges; financial services (including bank accounts, ATMs, and credit cards); cities; a network of competent workers that can help you to fix problems; postal services (that delivers fast); national parks; street cleaning; public swimming pools (even private pools); firefighters; parks; online shopping; weather forecasts; and a waste management system.

Tools and technologies: Pencils, ballpoint pens, and paper; lawnmowers; cars; car mechanics; bicycles; power tools like drills (even battery-powered ones); a watch; computers and laptops; smartphones (with GPS and a good camera); being able to stay in touch with distant friends or family members (or even visiting them); GPS; batteries; telephones and mobiles; video calls; WiFi; and the internet right here.

Social services: Caretakers for those who are disabled, sick, or elderly; protection from crime; non-profit organizations financed by the public, by donations or by philanthropies; insurance (against many different risks); and a legal system with judges and lawyers that implement the rule of law.

There is also a wide range of transfer payments, which in themselves are not services (they are transfers) but which become more affordable as a society becomes more prosperous: sick leave and disability benefits; unemployment benefits; and being able to help others with a regular donation of some of your income to an effective charity.6

Life and free time: tents; travel and holidays; surfboards; skis; board games; hotels; playgrounds; children’s toys; courses to learn hobbies (from painting to musical instruments or courses on the environment around us); a football; pets; the cinema, theater or a music concert; clothes (even comfortable and good-looking ones that keep you warm and protect you from the rain); shoes (even shoes for different purposes); shoe repair; the contraceptive pill and the ability to choose if and when to have children; sports classes from rock climbing to pilates and yoga; cigarettes (not all goods that people produce for each other are good for them);7 a musical instrument; a camera; and parties to celebrate life.

Health and staying well: Dentists; antibiotics; surgeries; anesthesia; mental health care from psychologists and psychiatrists; vaccines; public sewage; a haircut; a massage; midwives; ambulances; modern medicine; band-aids; pharmaceutical drugs; sanitary pads; toothbrushes; dental floss (some do floss); disinfectants; glasses; sunglasses; contact lenses; hearing aids; and hospitals — including very well-equipped, modern hospitals that offer CT scans, which include intensive care units and allow heart or brain surgery or organ transplants.

Specific needs and wishes: Most of the products listed above are generally helpful to people. But often, the goods and services that are most important to one individual are very specific.

As I’m writing this, I have a big cast on my left leg after I broke it. These days, I depend on products that I had no use for just three weeks ago. To move around, I need two long crutches, and to prevent thrombosis, I need to inject a blood thinner every day. After I broke my leg, I needed the service of nurses and doctors. They had to rely on a range of medical equipment, such as X-ray machines. To get back on my feet, I might need the service of physiotherapists.

We all have very specific needs or wishes for particular goods and services. Some needs arise from bad luck, like an injury. Others are due to a new phase in life — think of the specific goods and services you need when you have a baby or when you take care of an elderly person. And yet others are due to specific interests — think of the needs of a fisherman, or a pianist, or a painter.

All of these goods and services do not just magically appear. They need to be produced. At some point in the past, the production of most of them was zero, and even the most essential ones were extremely scarce. So, if you want to know what economic growth means for your life, look at the list above.

What is economic growth?

So, how can we define what economic growth is?

A definition that can be found in so many publications that I don’t know which one to quote is that economic growth is “an increase in the amount of goods and services produced per head of the population over a period of time.”

The definition in the Oxford Dictionary is almost identical: “Economic growth is the increase in the production of goods and services per head of population over a stated period of time”. And the definition in the Cambridge Dictionary is similar. It defines growth as “an increase in the economy of a country or an area, especially of the value of goods and services the country or area produces.”

In the following footnote, you find more definitions. Bringing these definitions together and taking into account the economic literature more broadly, I suggest the following definition: Economic growth is an increase in the quantity and quality of the economic goods and services that a society produces.

I prefer a definition that is slightly longer than most others. If you want a shorter definition, you can speak of ‘products’ rather than ‘goods and services’, and you can speak of ‘value’ rather than mentioning both the quantity and quality aspects separately.

The most important change in quantity is from zero to one when a new product becomes available. Many of the most important changes in history became possible when new goods and services were developed; think of antibiotics, vaccines, computers, or the telephone.

You find more thoughts on the definition of growth in the footnote.8

What are economic goods and services?

Many definitions of economic growth simply speak of the production of ‘goods and services’ collectively. This sidesteps a key difficulty in its definition and measurement. Economic growth is not concerned with all goods and services but with a subset of them: economic goods and services.

In everything we do — even in our most mundane activities — we continuously ‘produce’ goods and services in some form. Early in the morning, once we’ve brushed our teeth and made ourselves toast, we have already produced one service and one good. Should we count the tooth-brushing and the toast-making towards the economic production of the country we live in? The question of where to draw the line isn’t easy to answer. But we have to draw the line somewhere. If we don’t, we end up with a concept of production that is so broad that it becomes meaningless; we’d produce a service with every breath we take and every time we scratch our nose.

The line that we have to draw to define the economic goods and services is called the ‘production boundary’. The sketch illustrates the idea. The production boundary defines those goods and services that we consider when we speak about economic growth.

For a huge number of goods or services, there is no question that they are of the ‘economic’ type. But for some of them, it can be complicated to decide on which side of the production boundary they fall. One example is the question of whether the production of illegal goods should be included. Another is whether production within a household should be included — should we consider it as economic production if we grow tomatoes in our backyard and make soup from them? Different authors and different measurement frameworks have given different answers to these questions.9

There are some characteristics that are helpful in deciding on which side of the boundary a particular product falls.10 Economic goods and services are those that can be produced and that are scarce in relation to the demand for them. They stand in contrast to free goods, like sunlight, which are abundant, or those many important aspects in our lives that cannot be produced, like friendships.11 Our everyday language has this right: we don’t refer to the sun or our friendships as a good or service that we ‘produce’.

An economic good or service is provided by people to each other as a solution to a problem they are faced with, and this means that they are considered useful by the person who demands it.

A last characteristic that helps decide whether you are looking at an economic product is “delegability”. An activity is considered to be production in an economic sense if it can be delegated to someone else. This would include many of the goods and services on that long list we considered earlier but would exclude your breathing, for example.

Because economic goods are scarce in relation to the demand for them, human effort is required to produce them.12 A shorter way of defining growth is, therefore, to say that it is an increase in the production of those products that people produce for each other.

The majority of goods and services on that long list above are uncontroversially of the economic type — everything from the light bulbs and furniture in your home to the roads and bridges that connect your home with the rest of the world. They are scarce in relation to the demand for them and have to be produced by someone; their production is delegable, and they are considered useful by those who want them.

It’s worth recognizing that many of the difficulties in defining the production boundary arise from the effort to make measures of economic production as comparable as possible.

To give just one concrete example of the type of considerations that make the discussion about specific definitions so difficult, let’s look at how the production boundary is drawn in the housing sector.

Imagine two countries that are identical except for one aspect: home ownership. In Country A, everyone rents their homes, and the total sum of annual rent amounts to €2 billion per year. In Country B, everyone owns their own home, and no one pays rent. To provide housing is certainly an economic service, but if we only counted monetary transactions, then we would get the false impression that the value of goods and services in Country A is €2 billion higher than in Country B. To avoid such misjudgment, the production boundary includes the housing services that are provided without any monetary transactions. In National Accounts, statisticians take into account the “imputed rental value of owner-occupied housing” — those households who own their home get assigned an imputed rental value. In the imagined scenario, these imputed rents would amount to €2 billion in Country B so that the prosperity of people in these two countries would be judged to be identical.

It is the case more broadly that National Account figures (like GDP) do include important non-market goods and services that are not included in household survey measures of people’s income. GDP does not only include the housing services by owner-occupied housing but also the provision of most goods and services that are provided by the government or nonprofit institutions.

How can we measure economic growth?

Many discussions about economic growth are extraordinarily confusing. People often talk past one another.

I believe the key reason for this is that the discussion of what economic growth is gets muddled up with how it is measured.

While it is straightforward enough to define what growth is, measuring growth is very, very difficult.

In the worst cases, measures of growth are mixed up with a definition of growth. Growth is often measured as an increase in income or inflation-adjusted GDP per capita. But these measures are not the definition of it — just like life expectancy is a measure of population health but is certainly not the definition of population health.

To see how difficult it is to measure growth, take a moment to think about how you would measure it. How would you determine whether the quantity and quality of all economic goods and services produced by a society increased or decreased over time?

Finding a measure means that you have to find a way to express a huge amount of relevant information in a single metric. As the sketch shows, you have to first measure the quantity and quality of all the many, many goods and services that get produced and then find a way to aggregate all of these measurements into one summarizing metric. No matter what measure you propose for such a difficult task, there will always be problems and shortcomings in any proposal you might make.

In the following section, I will show four possible ways of measuring growth and present some data for each of them to see how they can inform us about the history of material living conditions.

Measuring economic growth by tracking access to particular goods and services

One possible way to measure growth is to make a list of some specific products that people want and to see what share of the population has access to them.

We do this very often at Our World in Data. The chart here shows the share of the world population that has access to four basic resources. All of these statistics measure some particular aspect of economic growth.

You can switch this chart to any country in the world via the “Change country” option. You will find that, judged by this metric, some countries achieved rapid growth — like Indonesia — while others only saw very little growth, like Chad.

The advantage of measuring growth in this way is that it is concrete. It makes clear what exactly is growing, and it’s clear which particular goods and services people gain access to.

The downside is that it only captures a small part of economic growth. There are many other goods and services that people want in addition to water, electricity, sanitation, and cooking technology.13

You could, of course, expand this approach of measuring growth to many more goods and services, but this is usually not done for both practical and ethical considerations:

One practical reason is that a list of all the products that people value would be extremely long. Keeping lists that track people’s access to all products would be a daunting task: hundreds of different toothbrushes, thousands of different dentists, hundreds of thousands of different dishes in different restaurants, and many millions of different books.14 If you wanted to measure growth across all goods and services in this way, you’d soon employ half the country in the statistical office.

In practice, any attempt to measure growth as access to particular products, therefore, means that you look only at a relatively small number of very particular goods and services that statisticians or economists are interested in. This is problematic for ethical reasons. It should not be up to the statisticians or economists to determine which few products should be considered valuable.

You might have realized this problem already when you read my list at the beginning of this text. You might have disagreed with the things that I put on that list and thought that some other goods and services were missing. This is why it is important to track incomes and not just access to particular goods: measuring people’s income is a way of measuring the options that they have rather than the choices that they make. It respects people’s judgment to decide for themselves what they find most important for their lives.

On our site, you find many more such metrics of growth that capture whether people have access to particular goods and services:

- This chart shows the share of US households having access to specific technologies.

- This chart shows the share that has health insurance.

- This chart shows access to schools.

Measuring economic growth by tracking the ratio between people’s income and the prices of particular goods and services

To measure the options that a person’s income represents, we have to compare their income with the prices of the goods and services that they want. We have to look at the ratio between income and prices.

The chart here does this for one particular product — books — and brings us back to the history of growth in the publishing sector that we started with.15 Shown is the ratio between the average income that a worker receives and the price of a book. It shows how long the average worker had to work to buy one book. Note that this data is plotted on a logarithmic axis.

Before the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, the price was often as high as several months of work. The fact that books were unaffordable for almost everyone should not be surprising. It corresponds to what we’ve seen earlier that it took a scribe several months to produce a single book.

The chart also shows how this changed when the printing press increased the productivity of publishing. As the labor required to produce a book declined from many months of work to less than a day, the price fell from months of wages to mere hours.

This shows us how an innovation in technology raises productivity and how an increase in production makes it more affordable. How it increases the options that people have.

Global inequality: How do incomes compare in countries around the world?

In the previous section, we measured growth as the ratio between income and the price of one particular good. But of course, we could do the same for all the many goods and services that people want. This ratio — the ratio between the nominal income that people receive and the prices that people have to pay for goods and services — is called “real income”.16

Real income = Nominal income / price of goods and services

Real income grows when people’s nominal income increases or when the prices of goods and services decrease.

In contrast to many of the other metrics on Our World in Data, a person’s real income does not matter for its own sake but because it is a means to an end. A means to many ends, in fact.

Economic growth — measured as an increase in people’s real income — means that the ratio between people’s income and the prices of what they can buy is increasing: goods and services become more affordable, and people become less poor. It is because a person has more choices as their income grows that economists care so much about these monetary measures of prosperity.

The two most prominent measures of real income are GDP per capita and people’s incomes, as determined through household surveys.

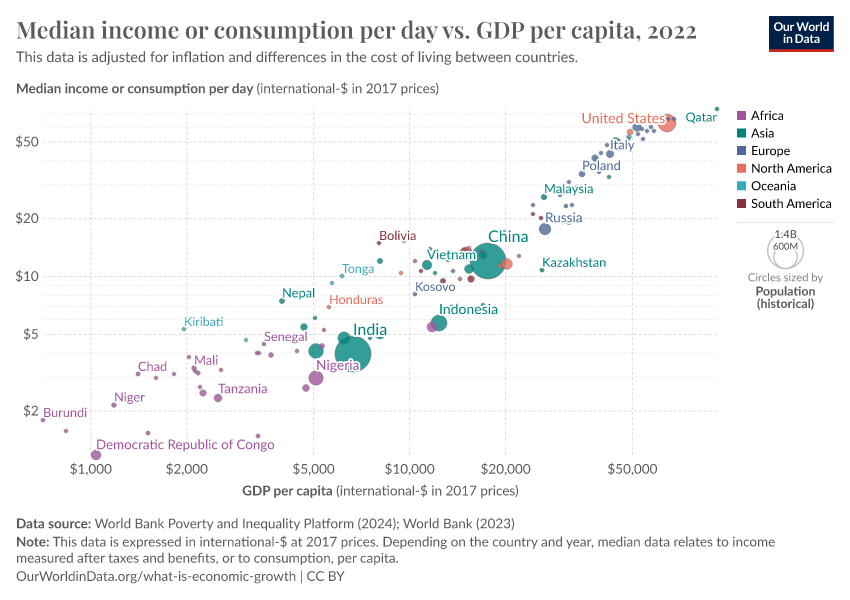

They are shown in this chart.

Before we get back to the question of economic growth, let’s see what these measures of real income tell us about the economic inequality in the world today.

Both measures show that global inequality is very large. In a rich country like Denmark, an average person can purchase goods and services for $61 a day, while the average Ethiopian can only afford goods and services that cost $3.50 per day.

Both measures of real incomes in this chart are measured in international dollars, which means that they take into account the level of prices in each country (using purchasing power parity conversion factors). This price adjustment is done in such a way that one international-$ is equivalent to the purchasing power of one US-$ in the US. An income of int.-$3.50 in Ethiopia, for example, means that it allows you to purchase goods and services in Ethiopia that would cost US-$3.50 in the US. All dollar values in this text are given in international dollars, even though I often shorten it to just the $-sign.

If you are living in a rich country and you want to have a sense of what it means to live in a poor country — where incomes are 20 times lower — you can imagine that the prices for everything around you suddenly increase 20-fold.17 If all the things you buy suddenly get 20-times more expensive your real income is 20-times lower. A loaf of bread doesn’t cost $2 but $40, a pair of jeans costs $400, and an old car costs $40,000. If you ask yourself how these price increases would change your daily consumption and your day-to-day life, you can get a sense of what it means to live in a poor country.

The two shown measures of real income differ:

- The data on the vertical axis is based on surveys in which researchers go from house to house and ask people about their economic situation. In some countries, people are asked about their income, while in other countries, people are asked about their expenditure — expenditure is income minus savings. In poor countries, these two measures are close to each other since poor people do not have the chance to save much.

- On the other hand, GDP per capita starts at the aggregate level and divides the income of the entire economy by the number of people in that country. GDP per capita is higher than per capita survey income because GDP is a more comprehensive measure of income. As we’ve discussed before, it includes an imputed rental value of owner-occupied housing and other differences, such as government expenditure.

Income as a measure of economic prosperity is much more abstract than the metrics we looked at previously. The comparison of incomes of people around the world in this scatterplot measures options, not choices. It shows us that the economic options for billions of people are very low. The majority of the world lives on very low incomes of less than $20, $10, or even $5 per day. In the next section, we’ll see how poverty has changed over time.

Global poverty and growth: How have incomes changed around the world?

Economic growth, as we said before, is an increase in the production of the quantity and quality of the economic goods and services that a society produces. The total income in a society corresponds to the total sum of goods and services the society produces — everyone’s spending is someone else’s income. This means that the average income corresponds to the level of average production, so the average income in a society increases when the production of goods and services increases.

Average production = average income

In this final section, let’s see how incomes have changed over time, first as documented in survey incomes and then via GDP per capita.

Measuring economic growth by tracking incomes as reported in household surveys

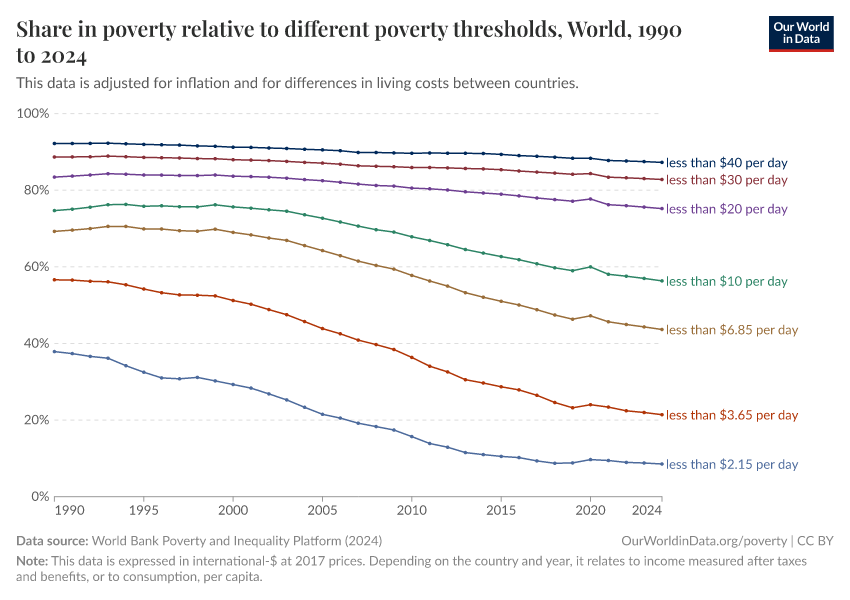

The chart shows the income of people around the world over time, as reported in household surveys. It shows the share of the world population that lives below different poverty lines: from extremely low poverty lines up to $30 per day, which corresponds to notions of poverty in high-income countries.

Many of the poorest people in the world rely on subsistence farming and do not have a monetary income. To take this into account and make a fair comparison of their living standards, the statisticians who produce these figures estimate the monetary value of their home production and add it to their income.

Again, the prices of goods and services are taken into account: these are measures of real incomes. As explained before, incomes are adjusted for price differences between countries, and they are also adjusted for inflation. As a consequence of these two adjustments, incomes are expressed in international dollars in 2021 prices, which means that these income measures express what you would have been able to buy with US dollars in the US in 2021.

Global economic growth can be seen in this chart as an increasing share of the population living on higher incomes. In 2000, around 70% of the world lived on less than $8.30 per day. In the following 25 years, this share fell by 25 percentage points.

In 2020 and 2021 — during the economic recession that followed the COVID-19 pandemic — the size of the world economy declined, and the share of people in poverty increased.

The data shows that global poverty has declined, no matter what poverty line you choose. It also shows that the majority of the world still lives on very low incomes. As we’ve seen, we can describe the same reality from the production side: the global production of the goods and services that people want has increased, but there is still not enough production of even very basic products. Most people in the world do not have access to them.

An advantage of household survey data over GDP per capita is that it captures the inequality of incomes within a country. You can explore this inequality with this chart by switching to see the data for an individual country via the ‘Change country’ button.

Measuring economic growth by tracking GDP per capita

GDP per capita is a broader measure of real income, and in contrast to survey income, it also takes government expenditures into account. A lot of thinking has gone into the construction of this very prominent metric so that it is comparable not only over time but also across countries. This makes it especially useful as a measure to understand the economic inequality in the world, as we’ve seen above.18

Another advantage of this measure is that historians have reconstructed estimates of GDP per capita that go back many centuries. This historical research is an extremely laborious task, and researchers have dedicated many years of work to these reconstructions. The “Maddison Project” brings together these long-run reconstructions from various researchers, and thanks to these efforts, we have a good understanding of how incomes have changed over time.

The chart shows how average incomes in different world regions have changed over the last two centuries. Looking at the latest data, you see again the very large inequality between different parts of the world today. You now also see the history of how we got here: small increases in production in some world regions and very large increases in those regions where people have the highest incomes today.

One of the very first countries to achieve sustained economic growth was the United Kingdom. In this chart, we see the reconstructions of GDP per capita in the UK over the last centuries.

It is no accident that the shape of this chart is very similar to the chart on book production at the beginning of this text — very low and almost flat for many generations and then quickly rising. Both of these developments are driven by changes in production.

Average income corresponds to average production, and societies around the world were able to produce very few goods and services in the past. There were no major exceptions to this reality. As we see in this chart, global inequality was much lower than today: the majority of people around the world were very poor.

To get a sense of what this means, you can again take the approach we’ve used to understand the inequality in the world today. When incomes in today’s rich countries were 20 times lower, it was as if all the prices around you today would suddenly increase 20-fold. But in addition to this, you have to consider that all the goods and services that were developed since then disappeared — no bicycle, no internet, no antibiotics. All that’s left for you are the goods and services of the 17th century, but all of them are 20 times more expensive than today. The majority of people around the world, including in today’s richest countries, live in deep poverty.

Just as we’ve seen in the history of book production, this changed once new production technologies were introduced. The printing press was an exceptionally early innovation in production technology; most innovations happened in the last 250 years. The starting point of this rise out of poverty is called the Industrial Revolution.

The printing press made it possible to produce more books. The many innovations that made up the Industrial Revolution made it possible to increase the production of many goods and services. Compare the effort that it takes for a farmer to reap corn with a scythe to the possibilities of a farmer with a tractor or a combined harvester, or think of the technologies that made overland travel faster — from walking on foot to traveling in a horse buggy to taking the train or car; or think of the effort it took to build those roads that the buggies once traveled on with the modern machinery that allows us to produce the corresponding public infrastructure today.

The production of a myriad of different goods and services followed trajectories very similar to the production of books — flat and low in the past and then steeply increasing. The rise in average income that we see in this chart is the result of the aggregation of all these production increases.

In the past, before societies achieved economic growth, the only way for anyone to become richer was for someone else to become poorer; the economy was a zero-sum game. In a society that achieves economic growth, this is no longer the case. When average incomes increase, it becomes possible for people to become richer without someone else becoming poorer.

This transition from a zero-sum to a positive-sum economy is the most important change in economic history (I wrote about it here) and made it possible for entire societies to leave the extreme poverty of the past behind.

Conclusion: The history of global poverty reduction has just begun

The chart shows the global history of extreme poverty and economic growth.

In the top left panel, you can see how global poverty has declined as incomes increased; in the other eight panels, you see the same for all world regions separately. The starting point of each trajectory shows the data for 1820 and tells us that two centuries ago, the majority of people lived in extreme poverty, no matter where in the world they were at home.

Back then, it was widely believed that widespread poverty was inevitable. But this turned out to be wrong. The trajectories show how incomes and poverty have changed in each world region. All regions achieved growth — the goods and services that people need saw their production and quality increase — and the share living in extreme poverty declined.19

This historical research was done by Michail Moatsos and is based on the “cost of basic needs” approach as suggested by Robert Allen (2017) and recommended by the late Tony Atkinson.20 The name “extreme poverty” is appropriate as this measure is based on an extremely low poverty threshold. It takes us back to what I mentioned at the very beginning; this historical research tells us — as the author puts it — that three-quarters of the world "could not afford a tiny space to live, food that would not induce malnutrition, and some minimum heating capacity.”

Since then, all world regions have made progress against extreme poverty — some much earlier than others — but in particular, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the share of people living in deep poverty is still very high.

The last two centuries were the first time in human history that societies have achieved sustained economic growth, and the decline of global poverty is one of the most important achievements in history. But it is still a very long way to go.

This is what we see in this final chart.21 The red line shows the share of people living in extreme poverty we discussed. Additionally, you now also see the share living on less than $3.65, $6.85, and $30 per day.

The world today is very unequal, and the majority of the world still lives in poverty: 46% live on less than $8.30 per day, and 81% live on less than $30. Even after two centuries of progress, we are still in the early stages. The history of global poverty reduction has only just begun.

That the world has made substantial progress but nevertheless still has a long way to go is the case for many of the world’s very large problems. I’ve written before that all three statements are true at the same time: The world is much better, the world is awful, and the world can be much better. This is very much the case for global poverty. The world is much less poor than in the past, but it is still very poor, and it remains one of the largest problems we face.

Some writers suggest we can end poverty by simply reducing global inequality. This is not the case. I’m very much in favor of reducing global inequality, and I hope I do what I can to contribute to this. But it is important to be clear that a reduction of inequality alone would still mean that billions around the world would live in very poor conditions. Those who don’t see the importance of growth are not aware of the extent of global poverty. The production of many crucial goods and services has to increase if we want to end it. How much economic growth is needed to achieve this? This is the question I answered in this recent text.

To solve the problems we face, it is not enough to increase overall production. We also need to make good decisions about which goods and services we want to produce more of and which ones we want less of. Growth doesn’t just have a rate, it also has a direction, and the direction we choose matters — for our own happiness and for achieving a sustainable future.

I hope this text was helpful in making clear what economic growth is. It is necessary to remind ourselves of that because we mostly talk about poverty and growth in monetary terms. The monetary measures have the disadvantage that they are abstract, perhaps so abstract that we even forget what growth is actually about and why it is so important. The goods and services that we all need are not just there — they need to be produced — and economic growth means that the quality and quantity of these goods and services increase, from the food that we eat to the public infrastructure we rely on.

The history of economic growth is the history of how societies leave widespread poverty behind by finding ways to produce more of the goods and services that people need — all the very many goods and services that people produce for each other: look around you now.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Joe Hasell and Hannah Ritchie for very helpful comments on draft versions of this article.

Our World in Data presents the data and research to make progress against the world’s largest problems. This article draws on data and research discussed in our topic pages on Economic Inequality, Global Poverty, and Economic Growth.

Version history: In October 2023, I copy-edited this article; it was a minor update, and nothing substantial was changed.

Endnotes

Michail Moatsos (2021) — Global extreme poverty: Present and past since 1820. Published in OECD (2021), How Was Life? Volume II: New Perspectives on Well-being and Global Inequality since 1820, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d96efc5-en.

At the time when material prosperity was so poor, living conditions were extremely poor in general; close to half of all children died.

Historian Gregory Clark reports the estimate that scribes were able to copy about 3,000 words of plain text per day.

See Clark (2007) — A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Clark (2007). In it, Clark quotes his earlier working paper with Patricia Levin as the source of these estimates. Gregory Clark and Patricia Levin (2001) — “How Different Was the Industrial Revolution? The Revolution in Printing, 1350–1869.”

There are about 760,000 words in the bible (it differs between various translations and languages; here is an overview of some translations).

This implies that the production of one copy of the Bible meant 253.3 days (8.3 months) of daily work.

Copying the text was not the only step in the production process for which productivity was low. The ink had to be made, parchment had to be produced and cut, and many other steps involved laborious work.

Wikipedia’s article about scribes reports sources that estimate that the production time per bible was even longer than 8 months.

Clark himself states in the same publication that “Prior to that innovation, books had to be copied by hand, with copyists on works with just plain text still only able to copy 3,000 words per day. Producing one copy of the Bible at this rate would take 136 man-days.” Since the product of 136 and 3000 is only 408,000, it is unclear to me how Clark has arrived at this estimate — 408,000 words are fewer words than in the Tanakh and other versions of the bible.

The data is taken from Eltjo Buringh and Jan Luiten Van Zanden (2009) — Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, a Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries. In The Journal of Economic History Vol. 69, No. 2 (June 2009), pp. 409-445. Online here.

Western Europe in this study is the area of today’s Great Britain, Ireland, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Poland.

On the history and economics of book production, see also the historical work of Jeremiah Dittmar.

I’ve relied on several sources to produce this list. One source was the simple descriptions of the consumption bundles that are relied upon for CPI measurement — like this one from Germany’s statistical office. And I have also relied on the national accounts themselves.

This list is also inspired partly by this list of Gwern and I’m also grateful for the feedback that I got via Twitter to earlier versions of this list. [Here I shared the list on Twitter]

This is Hans Rosling’s talk on the magic of the washing machine — worth watching if you haven’t seen it.

Of course all of these transfer payments have a service component to them, someone is managing the payment of the disability benefits etc.

Because smoking causes a large amount of suffering and death I do not find cigarettes valuable, but my opinion is not what matters for a list of goods and services that people produce for each other. Whether some good is considered to be part of the domestic product depends on whether it is a good that some people want, not whether you or I want it. More on this below.

Very similar to the definitions given above is the definition that Kimberly Amadeo gives: “Economic growth is an increase in the production of goods and services over a specific period.”

“Economic growth is an increase in the production of economic goods and services, compared from one period of time to another” is the definition at Investopedia.

Alternatively, to my definition, I think it can be useful to think of economic growth as not directly concerned with the output as such but with the capacity to produce this output. The NASDAQ’s glossary defines growth in that way: “An increase in the nation's capacity to produce goods and services.”

Wikipedia defines economic growth as follows: “Economic growth can be defined as the increase in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy over time.” Definitions that are based on how growth is measured strike me as wrong — just like life expectancy is a measure of population health and hardly the definition of population health. I will get back to this mistake further below in this text.

An aspect that I emphasize more explicitly than others is the quality of the goods and services. People obviously do just care about the number of goods, and in the literature on growth, the measurement of changes in quality is a central question. Many definitions speak more broadly about the ‘value’ of the goods and services that are produced, but I think it is worth emphasizing that growth is also concerned with a rise in the quality of goods and services.

OECD — Measuring the Non-Observed Economy: A Handbook.

The relevant numbers are not small. For the US alone, “illegal drugs add $108 billion to measured nominal GDP in 2017, illegal prostitution adds $10 billion, illegal gambling adds $4 billion, and theft from businesses adds $109 billion” if they were to be included in the US National Accounts. This is according to the report by Rachel Soloveichik (2019) — Including Illegal Activity in the U.S. National Economic Accounts. Published by the BEA.

Ironmonger (2001) — Household Production. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Pages 6934-6939. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/03964-4

Or for some longer run data on the US: Danit Kanal and Joseph Ted Kornegay (2019) — Accounting for Household Production in the National Accounts: An Update, 1965–2017. In the Survey of Current Business.

Helpful references that discuss how the production boundary is drawn (and how it changed over time) are: Lequiller and Blades — Understanding National Accounts (available in various editions) Diane Coyle (2016) — GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691169859/gdp

The definition of the production boundary by Statistics Finland

Itsuo Sakuma (2013) — The Production Boundary Reconsidered. In The Review of Income and Wealth. Volume 59, Issue 3; Pages 556-567.

Diane Coyle (2017) — Do-it-Yourself Digital: The Production Boundary and the Productivity Puzzle. ESCoE Discussion Paper 2017-01, Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2986725

A more general way of thinking about free goods and services is to consider them as those for which the supply is hugely greater than the demand.

Their production, therefore, has an opportunity cost, which means that if someone obtains an economic good, someone is giving up on something for it — this can either be the person themselves or society more broadly. Free goods, in contrast, are provided with zero opportunity cost to society.

It is also the case that the international statistics on these measures often have very low cutoffs for what it means ‘to have access’; this is, for example, the case for what it means to have access to energy.

10 years ago, Google counted there were 129,864,880 different books, and since then, the number has increased further by many thousands of new books every day.

This chart is from Jeremiah Dittmar and Skipper Seabold (2019) — New Media New Knowledge — How the printing press led to a transformation of European thought. I was unfortunately not able to find the raw data anywhere and could not redraw this chart; if someone knows where this (or comparable) data can be found, please let me know.

In the language of economists, the nominal value is measured in terms of money, whereas the real value is measured against goods or services. This means that the real income is the income adjusted for inflation (it is adjusted for the changes in prices of goods and services). Thereby, it allows comparisons that tell us the quantity and quality of the goods and services that people were able to purchase at different points in time.

I learned this way of thinking about it from Twitter user @Kirsten3531, who responded with this idea to a tweet of mine here https://twitter.com/Kirsten3531/status/1389553625308045317

We’ve discussed one such consideration that is crucial for comparability when we consider how to take into account the value of owner-occupied housing.

Whether economic growth translates into the reduction of poverty depends not only on the growth itself but also on how the distribution of income changes. The poverty metrics shown in this chart and previous charts take both aspects — the average level of production/income and its distribution — into account.

Michail Moatsos (2021) — Global extreme poverty: Present and past since 1820. Published in OECD (2021), How Was Life? Volume II: New Perspectives on Well-being and Global Inequality since 1820, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d96efc5-en.

Jutta Bolt and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2021) — The GDP data in the chart is taken from The Long View on Economic Growth: New Estimates of GDP, How Was Life? Volume II: New Perspectives on Well-being and Global Inequality since 1820, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d96efc5-en.

The latest data point for the poverty data refers to 2018, while the latest data point for GDP per capita refers to 2016. In the chart, I have chosen the middle year (2017) as the reference year.

The ‘cost of basic needs’ approach was recommended by the ‘World Bank Commission on Global Poverty’, headed by Tony Atkinson, as a complementary method in measuring poverty.

The report for the ‘World Bank Commission on Global Poverty’ can be found here.

Tony Atkinson — and, after his death, his colleagues — turned this report into a book published as Anthony B. Atkinson (2019) — Measuring Poverty Around the World. You can find more information on Atkinson’s website.

The CBN-approach Moatsos’ work is based on what was suggested by Allen in Robert Allen (2017) — Absolute poverty: When necessity displaces desire. In American Economic Review, Vol. 107/12, pp. 3690-3721, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20161080.

Moatsos describes the methodology: “In this approach, poverty lines are calculated for every year and country separately, rather than using a single global line. The second step is to gather the necessary data to operationalize this approach alongside imputation methods in cases where not all the necessary data are available. The third step is to devise a method for aggregating countries’ poverty estimates on a global scale to account for countries that lack some of the relevant data.” In his publication — linked above — you find much more detail on all of the shown poverty data. The speed at which extreme poverty declined increased over time, as the chart shows. Moatsos writes, “It took 136 years from 1820 for our global poverty rate to fall under 50%, then another 45 years to cut this rate in half again by 2001. In the early 21st century, global poverty reduction accelerated, and in 13 years, our global measure of extreme poverty was halved again by 2014.”

These are also global poverty estimates based on household surveys as we discussed above, but expressed in 2011 and 2017 international dollars. Since the publication of this article, the World Bank has updated its poverty data and now measures incomes in 2021 international-$. Explore the latest data in our Poverty Data Explorer.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2021) - “What is economic growth? And why is it so important?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/what-is-economic-growth.html' [Online Resource] (archived on March 4, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-what-is-economic-growth,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {What is economic growth? And why is it so important?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2021},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/what-is-economic-growth.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.