Breaking out of the Malthusian trap: How pandemics allow us to understand why our ancestors were stuck in poverty

For much of human history, our ancestors were trapped in an economy in which incomes were determined by the size of the population. The Industrial Revolution ended this Malthusian economy and made it possible for a country to leave abject poverty behind.

Note: Since the publication of this article, the World Bank has updated its poverty data. See the note at the end for more information.

Poor material living conditions have been such a persistent and pervasive reality that, for much of human history, it was unimaginable that they could ever be different.

Poverty did not change and so it was easy to believe that poverty was unchangeable. The Reverend Thomas Malthus wrote about the living conditions in his native England “It has appeared that from the inevitable laws of our nature, some human beings must suffer from want. These are the unhappy persons who, in the great lottery of life, have drawn a blank.”1

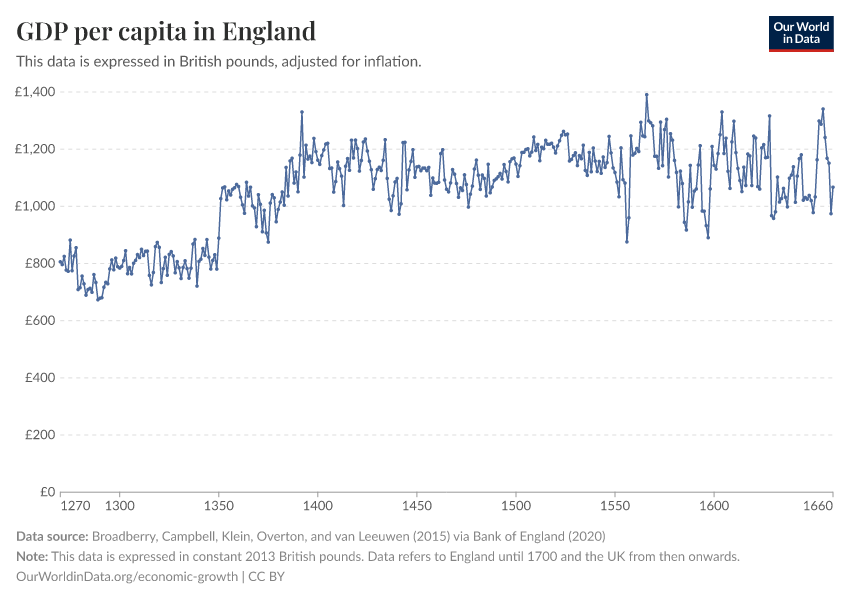

Reconstructions of living conditions over the long-run suggest that when Malthus wrote these words in 1789, he was right about the past. As the visualization here shows, GDP per capita — the average income of people — had remained extremely low.

But Malthus turned out to be very wrong about the world after his death: In the two centuries since then, many countries broke out of the stagnation of the past, achieved economic growth, and reduced poverty.

Why is this? Why were our ancestors stuck in poverty for so long?

Economic growth today is achieved when economies become more productive. Productivity can increase due to new technologies — a farmer with a tractor is more productive than a farmer with an ox; a cargo ship is more productive in delivering goods than a horse buggy; and a factory with power looms is more productive in making the clothes you are wearing than a weaver working by himself. And productivity can increase through social and economic changes — trade makes it possible to grow food where agricultural productivity is high and better education makes it possible for people to become more productive at their jobs.

Our ancestors also achieved productivity increases, but — as we will see — this didn’t lead to better living standards but to more people.

Understanding this mechanism – called the Malthusian Trap – allows us to understand why our ancestors remained in poverty and it explains why sustained economic growth, where the material living conditions of a population increase over several generations, was not achieved until just a few generations ago.2

Living standards and pandemics in Medieval England

England was the first country to achieve sustained growth and is also a country for which historians have produced very careful reconstructions. For both of these reasons, England is the country we will look at in detail.

The careful reconstructions of economic historians, including detailed accounts of what was produced and consumed through the centuries, allow us to understand the dynamics of poverty and prosperity in the past. For GDP per capita to capture people’s living conditions historians assign a monetary value to the goods and services that people consumed. This is crucial because it means that historians take into account that people lived off products and services that were not bought and sold in the market, which importantly often includes their own production.3

And it wasn't only GDP per capita, living standards remained poor by many metrics as the chart below on the history of living conditions in England shows. Life expectancy fluctuated up and down at around 40 years without a trend, access to education and literacy were poor, child deaths were very common, and food supply remained extremely poor during these centuries.

The chart here zooms into the economic history of medieval England from 1270 to 1660.4 Although these 400 years are only a fraction of humanity’s long history, they allow us to understand the mechanism that for so long trapped our ancestors in poor material living conditions.

The ups and downs in the medieval economy are small when compared with the rise in prosperity since then, but it is clear that, in the context of their time, these were significant changes.

Most prominently we see that very suddenly, in the middle of the 14th century, incomes jumped up to a substantially higher level. Until the mid-1340s the English lived on around £800 per year; but then, in a period of less than five years, incomes increased to over £1000. Prosperity kept on increasing so that by the end of the century they reached a new plateau at close to £1,200 per year. Within half a century the English saw their incomes increase by almost 50%.

This rise in prosperity happened during some of the most terrible decades in English history. In June 1348 the plague arrived in England and it quickly became a pandemic of enormous dimensions that ravaged the entire island: It is estimated that in the three years after 1348 the population of the country declined from 4.8 million to 2.6 million. Almost half of the English population died.5

The devastation caused by the Black Death was so large that it is clearly visible in our reconstructions of the long-run development of the world population.

Why did one of the very worst pandemics the world has ever seen coincide with a rise in living standards?

In the Malthusian economy living standards are determined by the size of the population

Today we are used to seeing the total output of the economy grow. Since 1960, the total output of the UK economy has grown 300% and the world economy has grown more than 600% (see here). Not only has the total size of the economy grown over the last century, but per capita incomes have increased too. This tells us that the growth in economic output has been faster than the growth of the population.

In humanity’s long history rapid economic growth is a very new phenomenon. Before the Industrial Revolution the total output of the economy did not change rapidly over time. The size of the pie remained largely unchanged from decade to decade. This difference with today’s economy is key to understanding the sudden increase of incomes that happened when the plague arrived in 1348.

The Malthusian trap: The zero-sum economy at work

The two panels in this chart here show the Malthusian economy at work and it will allow us to understand why the Black Death led to an increase of living standards for the survivors of the pandemic.6

The panel on top plots the size of the population on the horizontal axis against the total GDP of the English economy on the vertical axis; on the panel below you see the size of the population against GDP per capita. Since the total sum of production equals the total sum of income you can read this as per capita income or per capita production.

The red line in the bottom panel shows us what happened to per capita incomes when half of the population in England died during the Black Death: per capita incomes increased by almost 50%. The corresponding red line in the top panel shows us how this was possible. The size of the pie did not remain completely unchanged when the Black Death struck England, but the decline of total output was much smaller than the decline of the population. The result was a rapid increase of per capita incomes.

Before the Black Death, English farmers maximized agricultural output by eking out a living even on very unproductive lands, but as the pandemic killed half the population, the ratio between land and labor increased and the survivors were able to leave the least fertile lands behind and instead focussed on the more productive areas of the island. As a consequence of this, their productivity rose, and as a consequence their living standards increased.

Since the economy was largely agricultural we should expect that one of the plague’s economic benefits was a richer supply of food. Long-run reconstructions of the food supply in England confirm this expectation. Higher productivity also made it possible that working hours in the UK decreased and wages increased.7

With higher incomes, the population demanded more political power, and eventually revolted against oppression. The fight against high taxes and serfdom (unfree labour) culminated in the Great Rising of 1381.

The Black Death resulted in an increase in material living standards for the survivors, but precisely because the source of the gains was a one-off reduction in the population, the gains were a one-off step change towards better living standards.

That mechanism — the size of the population determining people’s living standards — is what trapped our ancestors in poverty. We see this in the following period.

In the two centuries after 1450 England’s economy more than doubled as the blue line in the top panel shows. But this increase of total production did not lead to an increase in income per person as the bottom panel shows. This is the other side of the Malthusian Trap: a growing size of the economy did not lead to higher living standards, but to more people. In the two-hundred years until 1650 the growing output of the English economy was shared by a population that grew at the same rate. As a consequence living standards did not increase. The average person remained as poor as they were.

These two periods — shown by a red and a blue line in the chart — show us how the pre-growth economy worked. Living standards were determined in a brutal zero-sum game:

- Any increase in productivity would only lead to a brief increase in living standards, because it ultimately led to an increasing size of the population that left everyone as poorly off as before. This is what we see in the period from 1450 to 1650.

- That the reverse logic also applied is what we can learn from the pandemics. When a large share of the population died it left the survivors better off. This is what the episode of the Black Death shows us.8

It was the Reverend Thomas Malthus who described this logic of the pre-growth economy most famously. His realization that any increase in productivity would not increase living standards but only the size of the population is what he had in mind as the “inevitable laws of our nature” that ensured that poverty would always remain the condition of the masses.

Until today the academic literature refers to this logic of the pre-growth economy as the Malthusian Economy. The key insight of the Malthusian model is that there was a tight link between the size of the population and the level of living standards. In the very long time in which humanity was trapped in the Malthusian economy it was births and deaths that determined incomes. More births, lower incomes. More deaths, higher incomes.

If the size of the total output is not changing much over time then anyone’s gain needs to be someone else’s loss and anyone’s loss will be someone else’s gain. This is why the pre-growth economy was a zero-sum game.

Because of this zero-sum logic, efforts to support the poor used to be regularly met with scorn in the pre-growth economy. The Malthusian argument against redistribution was that any well-meaning effort would inevitably make everyone worse off: improving the living conditions of the poor would lead to fewer deaths and the ensuing increase of the population would decrease everyone’s living standards.9

Breaking out of the trap

The chart above also shows when England broke out of the Malthusian trap — the first country in the world to do so. From around 1685 onwards we see what Malthus thought was impossible: the speed of innovation fueling productivity growth became so fast that both the size of the population and income per person started growing at the same time.

The economy changed from a zero-sum game to a positive-sum game in which the living standards of people increased over time and the share of English people in extreme poverty declined rapidly.

The chart above shows the early period of this escape until the 1750s. What happened after?

The trends after the 1750s are so different that it is best to explore them in an interactive visualization: by default the interactive chart shows the same period as the chart above (1270 to 1750), but once you pull the time-slider below the chart to the right you see the change up to the present.

After England escaped the trap, per capita incomes grew very rapidly and today’s living standards are far higher than in the past: economic growth increased average incomes from around £1,200 in the centuries after the Black Death to £29,000 today: a 24-fold increase.

From the zero-sum to the positive-sum economy

As we now know, Malthus wrote at an unfortunate time: he described the past well, but he was wrong about the future. He happened to understand the pre-growth economy at just that moment in history when his home country was breaking out of it.

Malthus was wrong to believe he had found an ‘inevitable law’ that would keep humanity in poverty forever. After Malthus’ death productivity grew far faster than the size of the population and persistent economic growth became a reality. To understand this is important because a large share of the world still lives on low incomes and the world has a very long way to go to end poverty everywhere. When England broke out of the trap we made the first step in that direction and since then the majority of countries around the world have followed and achieved some economic growth.

What we have seen here is the mechanism that kept our ancestors in poverty in the past. Malthus' insight was that in the pre-growth economy improvements in living standards were only possible when large fractions of the populations died. Any productivity gains on the other hand only led to a growing population.

COVID-19 shows us that in today’s economies the logic of Malthus no longer applies: the people in countries that suffered the highest death tolls can obviously not expect to see any economic benefits from the death of their compatriots. We do not live in a zero-sum economy anymore.

In a positive-sum economy your living standards are not determined by the productivity of your piece of land, but by the productivity of the economy that you are part of — the goods and services that you rely on are produced in a large-scale collaboration of millions of workers. Your economic well-being depends on them.

The fact that the pandemics in history lead to economic booms for the survivors allowed us to understand the pre-growth economy of the past. The fact that the COVID-19 pandemic is creating an economic downturn allows us to see the collaborative, positive-sum economy of our own time.

The episode of the Black Death showed us that in a zero-sum economy it is in people’s economic self-interest that others are worse off; more deaths means higher living standards for the survivors. The COVID pandemic in 2020 shows us how much the world has changed. In today’s positive-sum economy your own economic well-being depends on the well-being of others and it is in your own self-interest that others are healthy and well.

Continue reading on Our World in Data

More on the Malthusian Trap:

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Breck Yunits, and Tom Chivers for helpful feedback on this text and the visualizations.

Endnotes

Thomas Malthus (1798) – An Essay on the Principle of Population. Chapter X, paragraph 29, lines 12-15. Online here.

For very long-run estimates of total economic production see for example Michael Kremer (1993) – Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990. In The Quarterly Journal of Economics The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 108, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), pp. 681-716.For a global perspective see Robert Allen (2011) – Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. Online information.

Clark, Gregory (2007) – A Farewell to Alms. Princeton University Press. Information here.

Or in much more depth the literature recommended by Pseudorasmus here and here.

Or explore the historical data on living standards here.

For more detail on the measurement for historical GDP data, see our article and also Broadberry et al. (2015).

Broadberry, Stephen, Bruce Campbell, Alexander Klein, Mark Overton and Bas van Leeuwen (2015) – British Economic Growth 1270-1870 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107707603

The data shown here is taken from Broadberry, Stephen, Bruce Campbell, Alexander Klein, Mark Overton and Bas van Leeuwen (2015) – British Economic Growth 1270-1870 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107707603

To be consistent with the economic reconstructions I am relying on the same source here (Broadberry et al via Bank of England 2020). Other historians suggest similarly high mortality figures, some even higher than this. Benedictow suggests that 60% of the population of Europe died and also argues that a similarly high rate is true for England.

See Ole J. Benedictow (2004) – The Black Death 1346–1353: The Complete History. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

You also find interactive versions of these two panels on Our World in Data:

See Bank of England – A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data. Online here.

The graph is a striking illustration of a simple economic mechanism in action. Because the Black Death illustrates so well how the pre-growth economy worked it has been called “the mother of all natural experiments.”

See chapter X in Malthus 1789 quoted above. And for a broader recent discussion of this see Martin Ravallion (2013) — The Idea of Antipoverty Policy. NBER Working Paper No. 19210.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2020) - “Breaking out of the Malthusian trap: How pandemics allow us to understand why our ancestors were stuck in poverty” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260305-101825/breaking-the-malthusian-trap.html' [Online Resource] (archived on March 5, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-breaking-the-malthusian-trap,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {Breaking out of the Malthusian trap: How pandemics allow us to understand why our ancestors were stuck in poverty},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2020},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260305-101825/breaking-the-malthusian-trap.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.