Suicides

Every death from suicide is a tragedy. However, research shows that suicide rates can be reduced with greater understanding and support.

To do this, suicide should be recognized as a public health problem, and people should know that it can be prevented and its rates can be reduced.

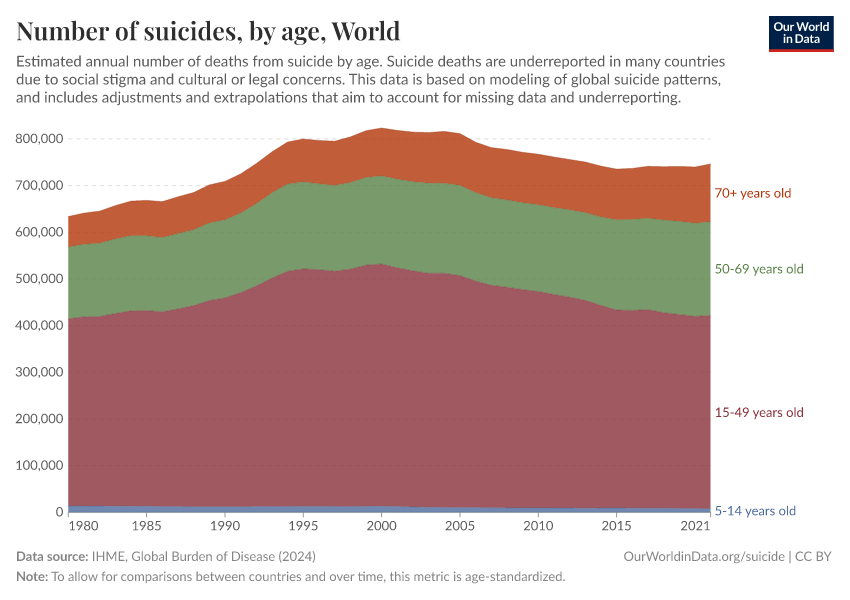

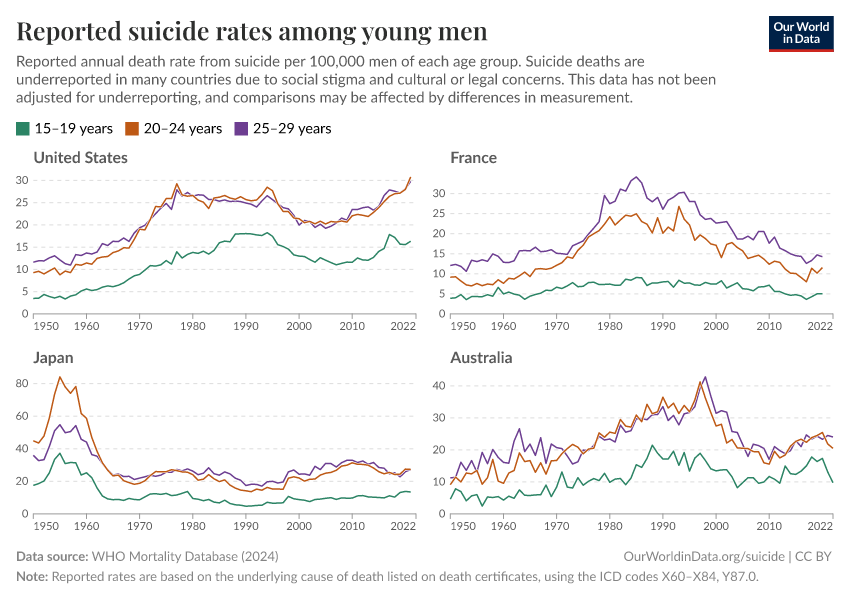

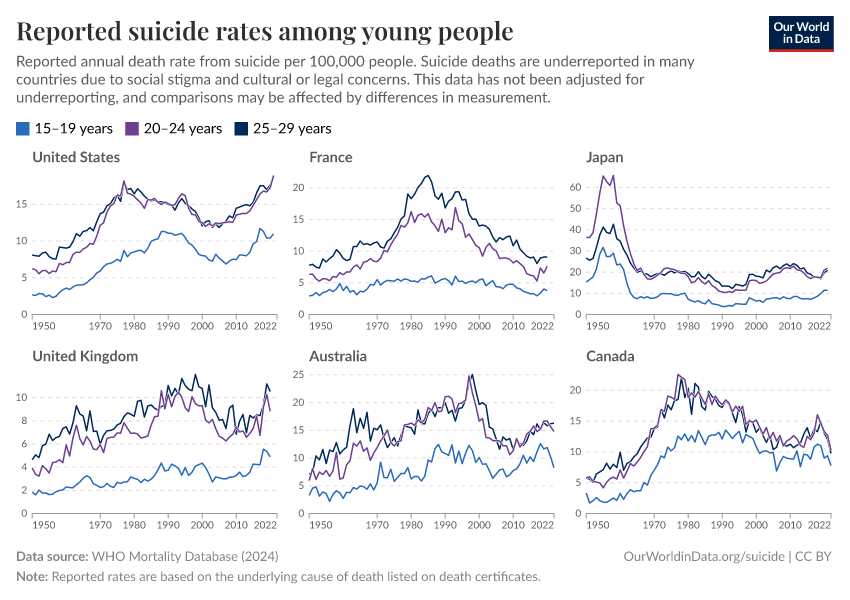

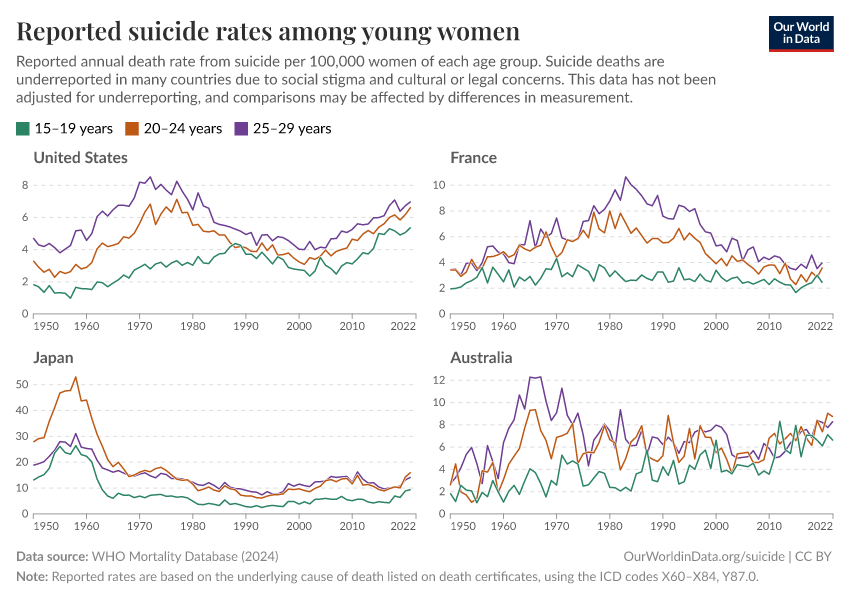

On this page, we show data on the prevalence of suicide across the world, its risk factors, and how these trends are changing over time.

If you are dealing with suicidal thoughts, you can receive immediate help by visiting resources such as findahelpline.com.

Key Charts on Suicides

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

Hawton, K. (2014). Suicide prevention: A complex global challenge. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70240-8

Naghavi, M. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ, l94. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94

Naghavi, M., Richards, N., Chowdhury, H., Eynstone-Hinkins, J., Franca, E., Hegnauer, M., Khosravi, A., Moran, L., Mikkelsen, L., & Lopez, A. D. (2020). Improving the quality of cause of death data for public health policy: Are all ‘garbage’ codes equally problematic? BMC Medicine, 18(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01525-w

Roth, G. A., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdela, J., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahpour, I., Abdulkader, R. S., Abebe, H. T., Abebe, M., Abebe, Z., Abejie, A. N., Abera, S. F., Abil, O. Z., Abraha, H. N., … Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392(10159), 1736–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7

Li, Z., Page, A., Martin, G., & Taylor, R. (2011). Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 72(4), 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008

Snowdon, J., & Choi, N. G. (2020). Undercounting of suicides: Where suicide data lie hidden. Global Public Health, 15(12), 1894–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1801789

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2019. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_cod_methods.pdf?sfvrsn=37bcfacc_5&ua=1

World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/341728/9789240026643-eng.pdf

Restrictions on the means of suicide are often used in preventative strategy. This may include regulation on pesticides, medication, and poisons, restrictions on gun access, and barriers at railways, buildings, bridges, and other hotspots.

Mann, J. J., Michel, C. A., & Auerbach, R. P. (2021). Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(7), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864

Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., Carli, V., Höschl, C., Barzilay, R., Balazs, J., Purebl, G., Kahn, J. P., Sáiz, P. A., Lipsicas, C. B., Bobes, J., Cozman, D., Hegerl, U., & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X

Osafo, J., Asante, K. O., & Akotia, C. S. (2020). Suicide prevention in the African region. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 41(S1), S53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32208755/

Rezaeian, M., & Khan, M. M. (2020). Suicide prevention in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 41(S1), S72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32208764/

Värnik, P., Sisask, M., Värnik, A., Arensman, E., Van Audenhove, C., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., & Hegerl, U. (2012). Validity of suicide statistics in Europe in relation to undetermined deaths: Developing the 2-20 benchmark. Injury Prevention, 18(5), 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040070

Gatov, E., Kurdyak, P., Sinyor, M., Holder, L., & Schaffer, A. (2018). Comparison of vital statistics definitions of suicide against a coroner reference standard: A population-based linkage study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(3), 152–160. Puigdefàbregas Serra, A., Freitas Ramírez, A., Gispert Magarolas, R., Castellà Garcia, J., Vidal Gutiérrez, C., Medallo Muñiz, J., Subirana Domènech, M., & Martínez Alcazar, H. (2017). Deaths with medicolegal intervention and its impact on the cause-of-death statistics in Catalonia, Spain. Spanish Journal of Legal Medicine, 43(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2017.02.001 Tøllefsen, I. M., Helweg-Larsen, K., Thiblin, I., Hem, E., Kastrup, M. C., Nyberg, U., Rogde, S., Zahl, P.-H., Østevold, G., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2015). Are suicide deaths under-reported? Nationwide re-evaluations of 1800 deaths in Scandinavia. BMJ Open, 5(11), e009120. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009120

Snowdon, J., & Choi, N. G. (2020). Undercounting of suicides: Where suicide data lie hidden. Global Public Health, 15(12), 1894–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1801789

Värnik, P., Sisask, M., Värnik, A., Arensman, E., Van Audenhove, C., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., & Hegerl, U. (2012). Validity of suicide statistics in Europe in relation to undetermined deaths: Developing the 2-20 benchmark. Injury Prevention, 18(5), 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040070

Snowdon, J., & Choi, N. G. (2020). Undercounting of suicides: Where suicide data lie hidden. Global Public Health, 15(12), 1894–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1801789

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2019. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_cod_methods.pdf?sfvrsn=37bcfacc_5

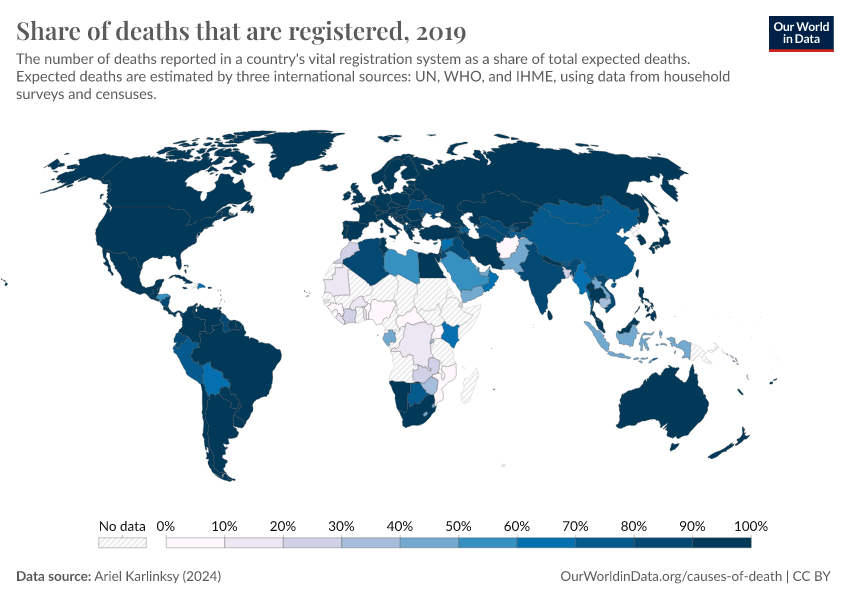

Karlinsky, A. (2021). International Completeness of Death Registration 2015-2019 [Preprint]. Public and Global Health. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.12.21261978https://github.com/akarlinsky/death_registration

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2019. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_cod_methods.pdf?sfvrsn=37bcfacc_5&ua=1

Hawton, K. (2014). Suicide prevention: A complex global challenge. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70240-8

Mann, J. J., Michel, C. A., & Auerbach, R. P. (2021). Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(7), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864

Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., Carli, V., Höschl, C., Barzilay, R., Balazs, J., Purebl, G., Kahn, J. P., Sáiz, P. A., Lipsicas, C. B., Bobes, J., Cozman, D., Hegerl, U., & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X

Nordentoft, M. (2011). Absolute Risk of Suicide After First Hospital Contact in Mental Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(10), 1058. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.113

The shape of this age–mortality curve is often described by the Gompertz function. Olshansky, S. J., & Carnes, B. A. (1997). Ever since Gompertz. Demography, 34(1), 1-15. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.2307/2061656.pdf

Lleras-Muney, A., & Moreau, F. (2022). A Unified Model of Cohort Mortality. Demography, 59(6), 2109–2134. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-10286336

Chen, Y.-Y., Yang, C.-T., Pinkney, E., & Yip, P. S. F. (2021). The Age-Period-Cohort trends of suicide in Hong Kong and Taiwan, 1979-2018. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 587–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.084

Kino, S., Jang, S., Gero, K., Kato, S., & Kawachi, I. (2019). Age, period, cohort trends of suicide in Japan and Korea (1986–2015): A tale of two countries. Social Science & Medicine, 235, 112385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112385

Martínez-Alés, G., Pamplin, J. R., Rutherford, C., Gimbrone, C., Kandula, S., Olfson, M., Gould, M. S., Shaman, J., & Keyes, K. M. (2021). Age, period, and cohort effects on suicide death in the United States from 1999 to 2018: Moderation by sex, race, and firearm involvement. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(7), 3374–3382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01078-1

Odagiri, Y., Uchida, H., & Nakano, M. (2011). Gender Differences in Age, Period, and Birth-Cohort Effects on the Suicide Mortality Rate in Japan, 1985-2006. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 23(4), 581–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539509348242

Wang, Z., Yu, C., Wang, J., Bao, J., Gao, X., & Xiang, H. (2016). Age-period-cohort analysis of suicide mortality by gender among white and black Americans, 1983–2012. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0400-2

Hawton, K. (2014). Suicide prevention: A complex global challenge. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70240-8

Naghavi, M. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ, l94. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94

Naghavi, M., Richards, N., Chowdhury, H., Eynstone-Hinkins, J., Franca, E., Hegnauer, M., Khosravi, A., Moran, L., Mikkelsen, L., & Lopez, A. D. (2020). Improving the quality of cause of death data for public health policy: Are all ‘garbage’ codes equally problematic? BMC Medicine, 18(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01525-w

Roth, G. A., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdela, J., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahpour, I., Abdulkader, R. S., Abebe, H. T., Abebe, M., Abebe, Z., Abejie, A. N., Abera, S. F., Abil, O. Z., Abraha, H. N., … Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392(10159), 1736–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7

Li, Z., Page, A., Martin, G., & Taylor, R. (2011). Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 72(4), 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina (2023) - “Suicides” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/suicide' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-suicide,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Lucas Rodés-Guirao and Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina},

title = {Suicides},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/suicide}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.