How do global statistics on suicide differ between sources?

To better monitor and prevent suicides globally, it's crucial to understand how they are measured and estimated by different sources.

Every suicide is a tragedy. To improve suicide prevention across countries and over time, it’s crucial to have good data on suicides.

Unfortunately, this data can be limited and difficult to interpret. Each data source has limitations; understanding them is critical to making sense of the available data.

In this article, I will describe where global suicide data comes from, its limitations, and how and why it varies between sources.

Where does data on suicides come from?

Reported data on suicides comes from death certificates

National data on suicides comes from the vital registry in each country. This is based on information from death certificates, which are filled in after people die.

A death certificate is typically filled in by health professionals, such as doctors or nurses, who have cared for the deceased person. They document the injuries or diseases that ultimately led to death and list what they believe is the “underlying cause of death” on the death certificate.1

You can read more about this in my article:

But for sudden deaths, including suicides, the process can be different.

Suicides can be determined by different professionals: general medical doctors, forensic medical doctors or pathologists (who perform an autopsy), the police, or the coroner.

A coroner is a government official who determines the cause of death on the death certificate.2 The coroner oversees investigations by medical professionals, forensic specialists, and law enforcement. They determine whether the death was caused by the person’s intention to harm themselves (“intentional self-harm”) rather than an accident, violence, or even a disease.

Several countries use a “coronial system” involving a coroner, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada.

In addition, the process of determining the cause of a sudden death can include performing an autopsy. In some countries, this is a requirement for all sudden deaths, or only those within specific age groups.3

After the cause of death is written on the death certificate, it is translated into an “ICD death code”, according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). ICD codes help researchers compile deaths for statistical purposes and better study their causes.

Researchers often use the following codes in the 10th edition of the ICD to classify suicides:4

- X60 to X84 — these codes represent intentional self-harm that directly leads to death;

- Y87.0 — these codes represent the consequences of intentional self-harm, for example, if it leads to medical complications that eventually lead to death.

You can read the full list of death codes and descriptions on the ICD-10’s website.

It’s important to note that this official definition doesn’t require evidence that the person intended to die but only that they intended to self-harm, which eventually led to death.5

Countries aggregate this data nationally and report it to the World Health Organization (WHO). This data is usually published several months or a few years later because it can take a long time for coroners to investigate deaths and collect information from across the country.6

What are the limitations of reported data?

Reported data from death certificates is limited in many countries

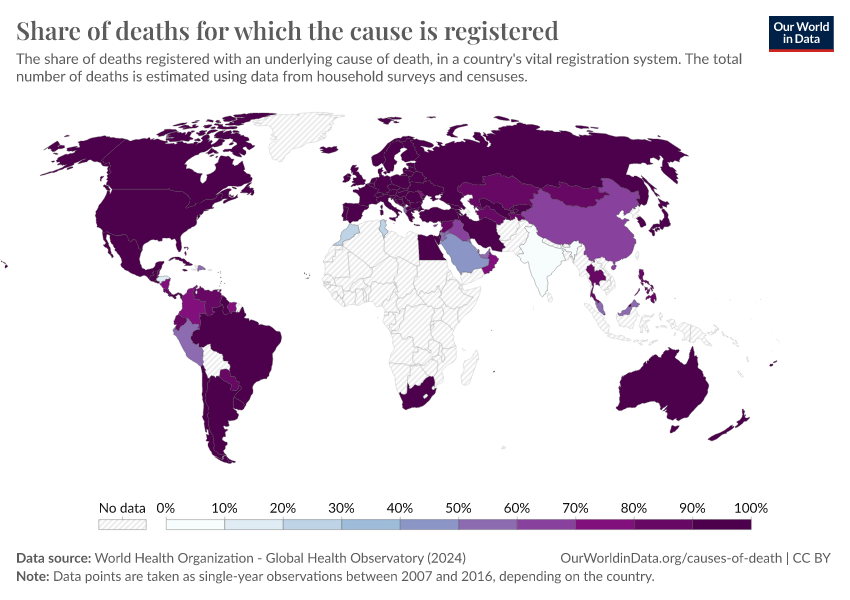

In many countries, data from death certificates is lacking, either partially or entirely. This is shown in the map below.

One reason is that some poorer countries lack functional vital registries to collect and store death certificates.

But even in countries with vital registries, many regions lack doctors, nurses, medical professionals, or coroners to investigate the cause of death. They may also lack medical records, resources, or legal enforcement to investigate each death.7

Because of this problem, many deaths in a country may go uncounted or be recorded without a cause of death. This directly reduces the ability to monitor and understand suicides.

Even when data is available, it can be complicated to make comparisons between countries because the process of determining a cause of death can vary. For example, there can be differences in the training of doctors, availability of medical records, and requirements for autopsies.

In addition, the particular legal or judicial system used to determine the cause of unexpected deaths can differ.

For example, in some countries, the police are responsible for determining the cause of death, while in others, a medical doctor, coroner, or judicial investigator determines the cause.8

Reported data in the WHO Mortality Database

The map below shows the reported suicide rate in each country in the WHO Mortality Database (WHO MDB). It republishes reported data from all countries that have registered at least 65% of all deaths with a cause of death.

As you can see, there is no data for many countries.

Reported data on suicides can be inaccurate

Within this general lack of data on causes of death, data on suicides can be especially limited.

One reason is that in some countries, it can be illegal to die by suicide, or “suicide” may not be an available option on a death certificate.9

Another reason is that there are often strong social taboos or legal consequences for suicides. Families and contacts may be unwilling to share information, and officials may be unwilling to declare them as suicides.10

Because of this, suicides tend to be underreported. They may be inaccurately classified under other causes — such as accidents, violence, or deaths of “undetermined intent”.11

Even well-recorded data on causes of death is not always comparable

We’ve seen several reasons why the quality of suicide data can greatly vary from country to country: a lack of vital registries, health professionals, medical records, coroner investigations, or other resources, and social consequences.

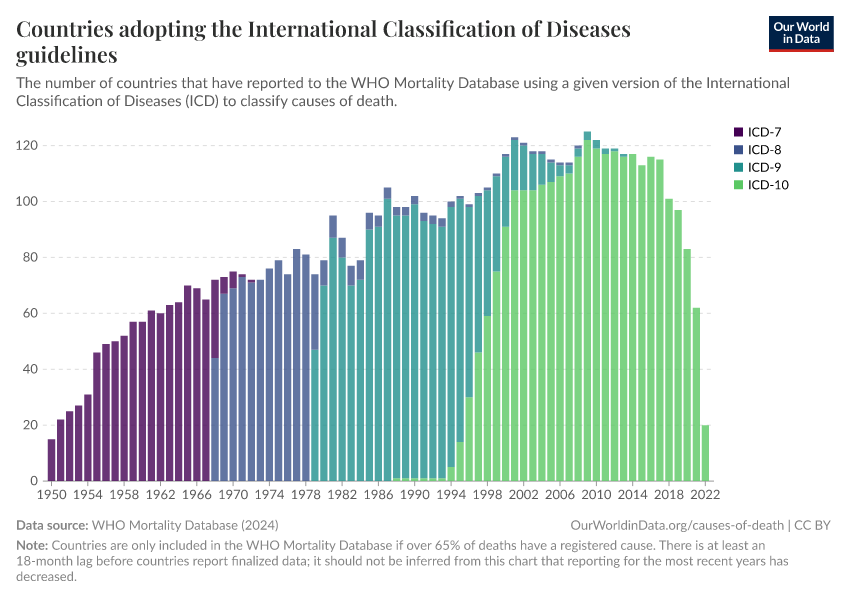

Yet another problem that makes comparisons difficult is that the ICD codes used to define causes of death have changed over time.

As the understanding of causes of death has evolved, new editions have been published. It can take years before each country adopts the newest version. This means countries may be using different versions of the ICD at any time.

The chart below shows, for each year, the number of countries that report deaths with a given version of ICD codes.

To address changes in classification over time, researchers try to harmonize data from different ICD versions. This aims to minimize changes in definitions and measurement, but it can be complex, and differences can remain.12

How are suicide rates estimated in places lacking reported data?

As we saw above, comprehensive data on suicides is often not available.

Researchers try to address these gaps by considering other data sources, such as hospital records or verbal autopsies, if they are available. They may also reclassify deaths from “other injuries” to “suicide”, based on assumptions about how many have been misclassified.

In the following section, we’ll compare how two global datasets develop estimates for suicide rates worldwide: the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s Global Burden of Disease (IHME’s GBD) study and the World Health Organization’s Global Health Estimates (WHO’s GHE).

These are summarized in the visualization below, along with the reported data collated in the WHO Mortality Database.

Suicide data in the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study

How does the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study make estimates of global suicide rates?

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, conducted by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), is a widely-used data source for global estimates of suicide.13

It uses a model to estimate how many people die from various causes, including suicide.

The process begins with collecting a wide range of data, such as death certificates, hospital records, and surveys. In addition, they look at available data on metrics related to suicide — such as sexual violence, depression, alcohol consumption, and healthcare access — which are used as covariates in the model.14

This data is then used to build several statistical models that predict death rates. The best-performing models are combined into a more accurate “ensemble model”.

The model relies on data from different places and times to extrapolate to the countries and periods where data is missing.

This method means that this data comes with significant uncertainties. The model also smooths out unusual spikes in the data, which could have occurred due to reporting errors.

Because some suicides can be initially misclassified or given garbage codes, the IHME’s model also reclassifies some deaths from “injuries of undetermined intent” to other causes, including suicide.15

The map below shows the GBD’s latest estimates of suicide rates worldwide.

What are the limitations of the estimates in the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study?

The IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study’s estimates of suicide rates provide insights into patterns and trends over time, but their estimates come with limitations.

First, the data used by the model can vary in quality, especially in countries lacking death certificate data and hospital records. Since the model estimates suicide rates for areas lacking in data by using information from other regions or historical trends, they may only be an approximation of actual death rates.

Second, since suicide deaths can be poorly investigated and recorded in many countries, the authors try to estimate the fraction of deaths listed with other causes that should be reclassified as suicides. This relies on assumptions of how many deaths from these causes are actually suicides. These assumptions rely on limited research from certain countries and periods and can be very uncertain.

Suicide data in the World Health Organization’s Global Health Estimates

How does the WHO’s Global Health Estimates study make estimates of global suicide rates?

The Global Health Estimates (GHE), provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), are an alternative source of global data on causes of death.

It uses a blend of official data from death certificates adjusted for potential underreporting and modeled estimates from the GBD.16

The estimates are developed by starting with data from countries where at least 80% of death certificates are considered “usable”.17

Data from these countries is then adjusted. Deaths originally classified under categories like “depression” or “injuries of undetermined intent” are reclassified to suicide, according to assumptions of how many deaths from these causes are actually suicides, based on a 2006 study.18

For countries that report a large share of their deaths with death certificate data, the WHO applies several adjustments to the data:

Data points are filled for the years or countries lacking sufficient data:

- For intermediate missing years, data is interpolated.

- Since data coverage from death certificates typically comes with a delay, projections of suicide rates are made beyond the last available data point. In the 2019 publication of the GHE, for example, data for the most recent years was based on projections from previous trends.19

For countries without the necessary death certificate data, the WHO GHE relies primarily on the estimates from the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.

However, for some causes of death, such as malaria, the WHO GHE uses its own estimation methods and applies a final adjustment to all causes to ensure that the deaths from each cause add up to the total number of deaths. This can lead to differences between IHME GBD and WHO GHE estimates.16

The map below shows the WHO GHE’s estimates of suicide rates worldwide.

What are the limitations of the WHO’s Global Health Estimates estimates?

The WHO’s Global Health Estimates come with several limitations.

One challenge is the way the WHO fills data gaps. For years or regions lacking data, the WHO interpolates and extrapolates data based on historical trends, which means recent estimates may not be accurate.

Another challenge is that the GHE reclassifies deaths from causes like “depression” or “injuries of undetermined intent” to “suicide” based on past research, which may not accurately represent current trends or regional differences.

In countries that lack sufficient data, the GHE incorporates data from the Global Burden of Disease study. While this helps complete the global picture, it means the estimates inherit the limitations of the GBD’s methodology.

How do the different sources of global data on suicides compare?

So far, we have looked at several different sources of data on suicides: reported suicide rates (in the WHO Mortality Database) and estimated suicide rates (from the IHME’s GBD study and the WHO’s GHE study).

The chart below shows a comparison of estimates from each data source.

You can see that different datasets contain different amounts of data over time.

Data from the WHO Mortality Database may start as early as the 1950s, depending on each country’s vital registration systems. New data and revisions to this dataset are published annually but come with a delay.

In contrast, IHME GBD estimates begin in the 1990s, and WHO GHE estimates begin in the 2000s.

You can see that some countries, such as India, lack reported suicide rates in the WHO Mortality Database because of poor levels of vital registration. What’s known about suicide trends in these countries only comes from estimates.

Other countries, such as South Africa, do have data on reported suicide rates but are believed to have severe underreporting.

Therefore, their data on suicide rates is adjusted by the IHME GBD and the WHO GHE based on the expected levels of underreporting and other available data.

As you can see on the chart, the rates published by the three sources have very large differences. Trendlines in some countries also vary between data sources.

In Venezuela, for example, reported suicide rates have declined since the 2000s, but reported data is currently unavailable for recent years. However, in the IHME GBD study and the WHO GHE, estimated suicide rates in Venezuela have not fallen, or have risen.

Conclusion

A range of challenges limit global suicide data, and understanding them is crucial to know how much progress is being made against suicides and whether new challenges are emerging.

In this article, we’ve looked at data from three sources:

- The WHO Mortality Database, which presents reported data using data from death certificates

- The IHME’s GBD study, which presents modeled data using a range of data sources

- The WHO’s GHE study, which presents a combination of modeled data and reported data that has been adjusted for underreporting

Reported data on suicides can be limited because of underreporting or misclassification in death certificates. In addition, countries can have different legal and cultural practices in determining causes of death, including suicide. Poor medical records, a lack of healthcare workers, and poverty can limit vital registration systems.

These limitations affect data from the WHO Mortality Database. Reported suicide rates are likely to be an underestimate of actual suicide rates, and are difficult to compare between countries, which can have different practices and national reporting systems.

Nevertheless, the WHO Mortality Database can help understand suicide trends over time in wealthier countries, especially if approaches to measure and classify suicide remain stable.

To account for the underreporting of suicides, researchers can use other data sources, such as the IHME’s GBD study and the WHO’s GHE study.

But these sources also have limitations: adjustments for underreporting of suicides are based on historical research that may be less valid today.

In addition, estimates are partially based on global patterns, and for some countries, there may be minimal information to make estimates of suicide rates and trends.

These limitations significantly affect estimates of poor countries, where different data sources can make very different estimates.

By improving data collection on suicide, we can improve our understanding of suicide trends globally and, ultimately, save more lives.

Endnotes

Brooks, E. G., & Reed, K. D. (2015). Principles and Pitfalls: A Guide to Death Certification. Clinical Medicine & Research, 13(2), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2015.1276

Värnik, P., Sisask, M., Värnik, A., Laido, Z., Meise, U., Ibelshäuser, A., Van Audenhove, C., Reynders, A., Kocalevent, R.-D., Kopp, M., Dosa, A., Arensman, E., Coffey, C., Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., Gusmão, R., & Hegerl, U. (2010). Suicide registration in eight European countries: A qualitative analysis of procedures and practices. Forensic Science International, 202(1–3), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.04.032

Paratz, E. D., Rowe, S. J., Stub, D., Pflaumer, A., & La Gerche, A. (2023). A systematic review of global autopsy rates in all-cause mortality and young sudden death. Heart Rhythm, 20(4), 607–613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.01.008

For suicides, the WHO Mortality Database (2024) uses codes X60 to X84.

The IHME’s Global Burden of Disease study (2019) uses codes X60-X64.9, X66-X83.9, and Y87.0.

The Human Mortality Database’s Cause of Death series (2024) uses codes X60 to X84.

See —

WHO Mortality Database (2024). Self-inflicted injuries. https://platform.who.int/mortality/themes/theme-details/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/MDB/self-inflicted-injuries

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2023). Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Cause List Mapped to ICD Codes. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2019-cause-icd-code-mappings

Human Cause of Death Database (2024). Format of the data files in the Human Cause-of-Death Database. https://mortality.org/File/GetDocument/hcd/docs/HCD_Formats.pdf

Although this is the official international definition of suicide, countries can vary in how they interpret it and measure it on death certificates.

Jakobsen, S. G., Nielsen, T., Larsen, C. P., Andersen, P. T., Lauritsen, J., Stenager, E., & Christiansen, E. (2023). Definitions and incidence rates of self-harm and suicide attempts in Europe: A scoping review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 164, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.05.066

A recent study looks at countries that have implemented “real-time suicide surveillance”, which involves more timely investigations and reporting of suicide data.

Benson, R., Rigby, J., Brunsdon, C., Corcoran, P., Dodd, P., Ryan, M., Cassidy, E., Colchester, D., Hawton, K., Lascelles, K., De Leo, D., Crompton, D., Kõlves, K., Leske, S., Dwyer, J., Pirkis, J., Shave, R., Fortune, S., & Arensman, E. (2023). Real-Time Suicide Surveillance: Comparison of International Surveillance Systems and Recommended Best Practice. Archives of Suicide Research, 27(4), 1312–1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2022.2131489

Mikkelsen, L., Phillips, D. E., AbouZahr, C., Setel, P. W., De Savigny, D., Lozano, R., & Lopez, A. D. (2015). A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. The Lancet, 386(10001), 1395-1406.

Aung, E., Rao, C., & Walker, S. (2010). Teaching cause-of-death certification: Lessons from international experience. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 86(1013), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2009.089821

Värnik, P., Sisask, M., Värnik, A., Laido, Z., Meise, U., Ibelshäuser, A., Van Audenhove, C., Reynders, A., Kocalevent, R.-D., Kopp, M., Dosa, A., Arensman, E., Coffey, C., Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., Gusmão, R., & Hegerl, U. (2010). Suicide registration in eight European countries: A qualitative analysis of procedures and practices. Forensic Science International, 202(1–3), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.04.032

Osafo, Joseph, Kwaku Oppong Asante, and Charity Sylvia Akotia. “Suicide Prevention in the African Region.” Crisis 41, no. Supplement 1 (March 1, 2020): S53–71. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000668

Rezaeian, Mohsen, and Murad Moosa Khan. “Suicide Prevention in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.” Crisis 41, no. Supplement 1 (March 1, 2020): S72–79. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000669

Snowdon, John, and Namkee G. Choi. “Undercounting of Suicides: Where Suicide Data Lie Hidden.” Global Public Health 15, no. 12 (December 1, 2020): 1894–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1801789

Snowdon, John, and Namkee G. Choi. “Undercounting of Suicides: Where Suicide Data Lie Hidden.” Global Public Health 15, no. 12 (December 1, 2020): 1894–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1801789

Naveed, S., Qadir, T., Afzaal, T., & Waqas, A. (2017). Suicide and Its Legal Implications in Pakistan: A Literature Review. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1665

Snowdon, John, and Namkee G. Choi. “Undercounting of Suicides: Where Suicide Data Lie Hidden.” Global Public Health 15, no. 12 (December 1, 2020): 1894–1901. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1801789

To adjust for changes when the entire ICD guidelines are revised, some researchers use 'bridge coding' methods to translate ICD codes used for older deaths to new codes.

Brocco, S., Vercellino, P., Goldoni, C. A., Alba, N., Gatti, M. G., Agostini, D., Autelitano, M., Califano, A., Deriu, F., Rigoni, G., & others. (2010). «Bridge Coding» ICD-9, ICD-10 and effects on mortality statistics. Epidemiologia e Prevenzione, 34(3), 109–119.

Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abrams, E. M., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., … Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

Global Burden of Disease study (2020). Methods for injuries including self-harm. Available online.

Naghavi, M., Makela, S., Foreman, K., O’Brien, J., Pourmalek, F., & Lozano, R. (2010). Algorithms for enhancing public health utility of national causes-of-death data. Population Health Metrics, 8(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-8-9

Naghavi, M. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ, l94. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94

Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abolhassani, H., Aboyans, V., Abrams, E. M., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., Abu-Raddad, L. J., Abushouk, A. I., … Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2021. Available online.

Usability is defined by the WHO as the share of all deaths in a region that have been registered with a cause of death on a death certificate, multiplied by the share of deaths that are assigned a meaningful cause of death.

This excludes “garbage codes”, a specific group of ICD codes that are often ill-defined or often incorrectly coded.

Some examples of ill-defined ICD codes include ‘sudden death’, ‘chest pain’, ‘heart failure’, ‘events of undetermined intent’, ‘cancer of unknown primary site’, and 'unspecified sepsis’.

These are considered garbage codes because they are not specific and refer to the immediate cause of death or the symptoms preceding it instead of the underlying cause.

They also provide little information because it is common for people to die from a cause within those broad categories.

Mathers, C. D., Lopez, A. D., & Murray, C. J. L. (2006). The Burden of Disease and Mortality by Condition: Data, Methods, and Results for 2001. In A. D. Lopez, C. D. Mathers, M. Ezzati, D. T. Jamison, & C. J. Murray (Eds.), Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11808/

See Table 4.1 of the Global Health Estimates methods for the specific years in each country for which data was available; years not included are based on interpolations or extrapolations. World Health Organization. (2020). WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2021. Available online.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani (2024) - “How do global statistics on suicide differ between sources?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260211-174736/how-do-global-statistics-on-suicide-differ-between-sources.html' [Online Resource] (archived on February 11, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-how-do-global-statistics-on-suicide-differ-between-sources,

author = {Saloni Dattani},

title = {How do global statistics on suicide differ between sources?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2024},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260211-174736/how-do-global-statistics-on-suicide-differ-between-sources.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.