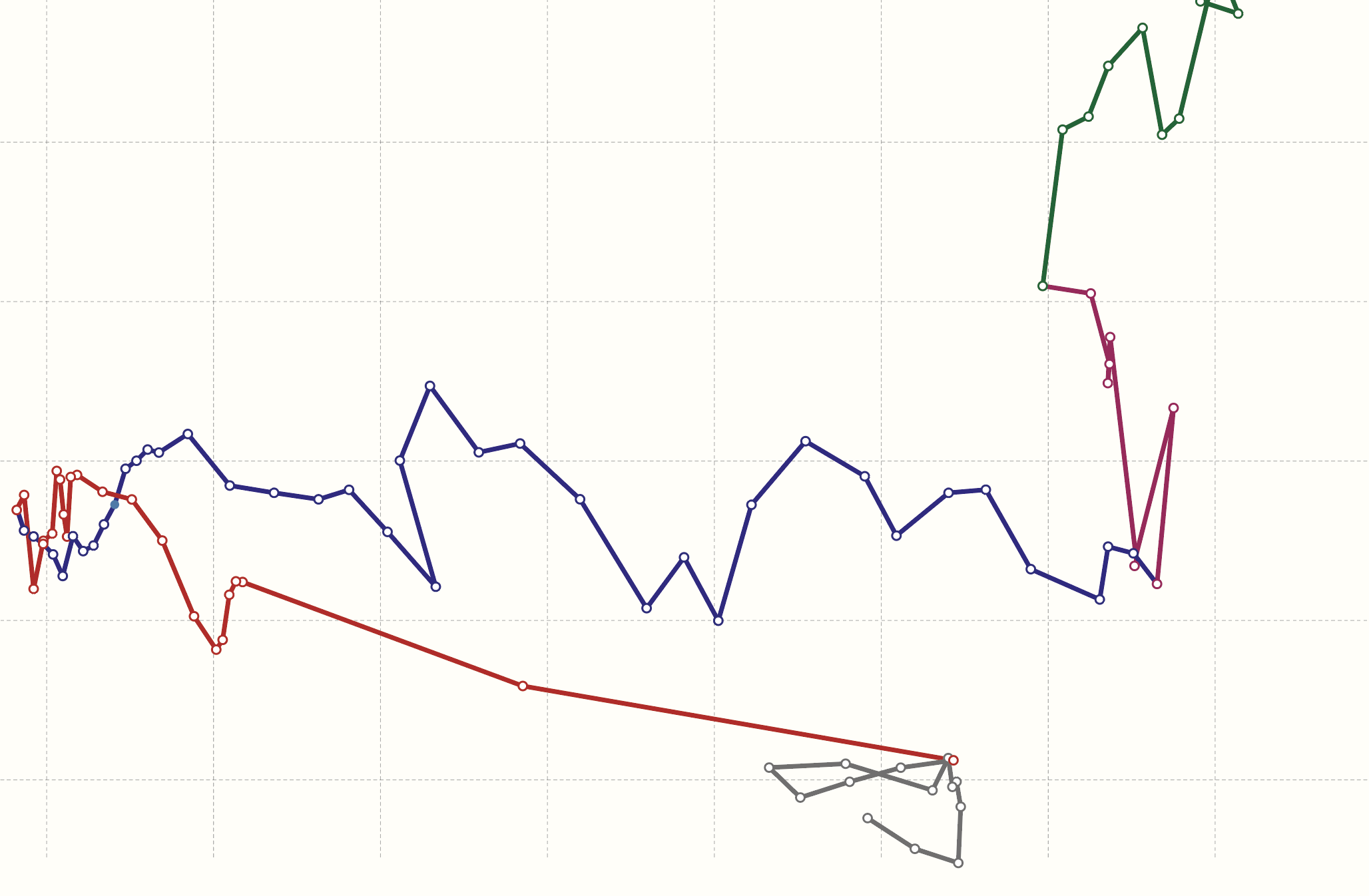

Real GDP per capita in 2011$

In two ways, this analysis leads to departures from the original Maddison approach and closer to the multiple benchmark approach as developed by the PWT. There is, to begin with, no doubt that the 2011 PPPs and the related estimates of GDP per capita reflect the relative levels of GDP per capita in the world economy today better than the combination of the 1990 benchmark and growth rates of GDP per capita according to national accounts. This information should be taken into account. At the same time, the underlying rule within the current Maddison Database is that economic growth rates of countries in the dataset should be identical or as close as possible to growth rates according to the national accounts (which is also the case for the pre 1990 period). For the post-1990 period we therefore decided to integrate the 2011 benchmarks by adapting the growth rates of GDP per capita in the period 1990–2011 to align the two (1990 and 2011) benchmarks. We estimated the difference between the combination of the 1990 benchmark and the growth rates of GDP (per capita) between 1990 and 2011 according to the national accounts, and annual growth rate from the 1990 benchmark to the 2011 benchmark. This difference is then evenly distributed to the growth rate of GDP per capita between 1990 and 2011; in other words, we added a country specific correction (constant for all years between 1990 and 2011) to the annual national account rate of growth to connect the 1990 benchmark to the 2011 benchmark. Growth after 2011 is, in the current update, exclusively based on the growth rates of GDP per capita according to national accounts.

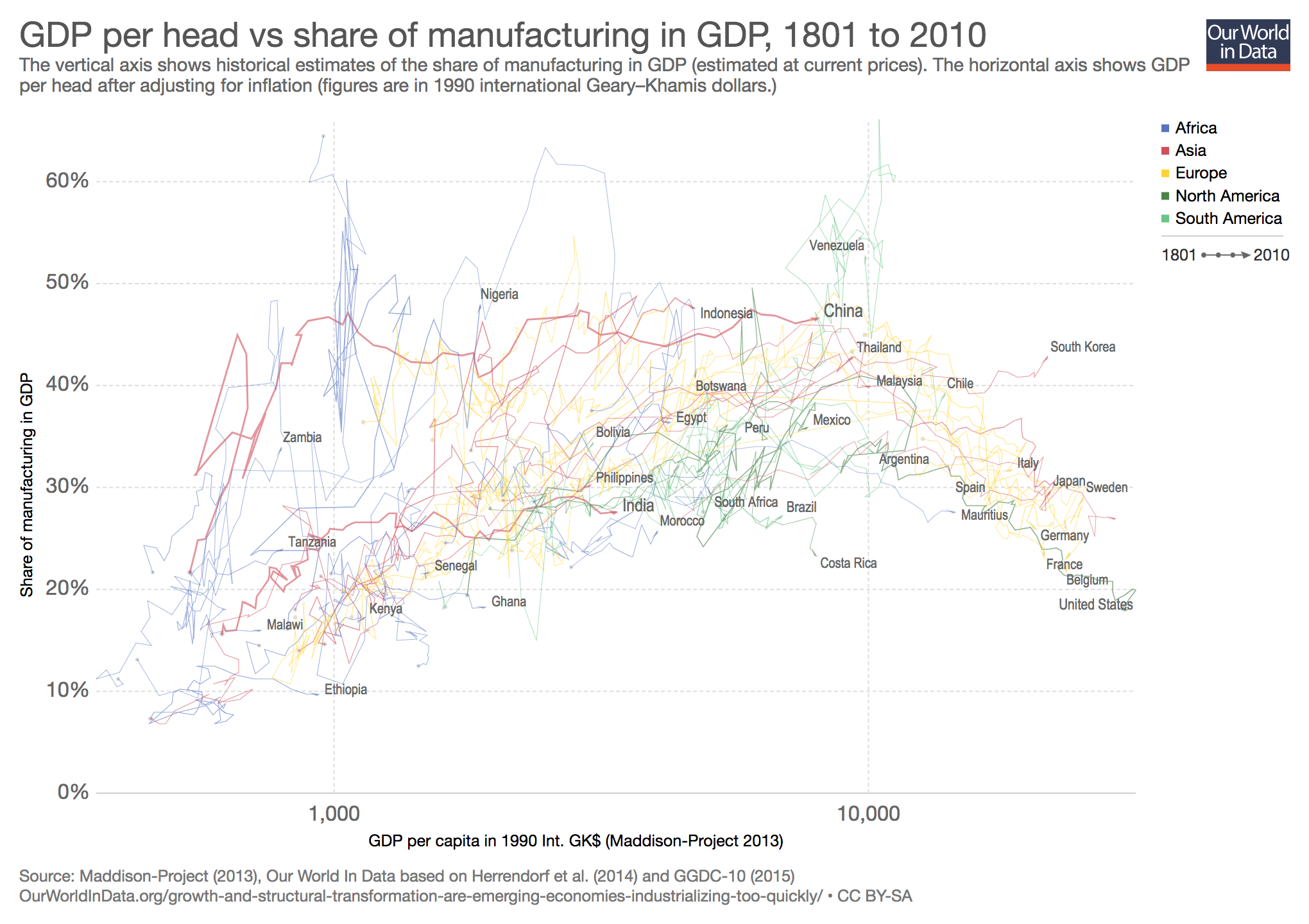

We also use the collected set of historical benchmark estimates to fine tune the dataset for the pre-1940 period, but only in those cases where the quality of the benchmark was high and there were multiple benchmarks to support a revision. The most important correction concerns the US/UK comparison. The conventional picture, based on the original 1990 Maddison estimates, indicated that the US overtook the UK as the world leader in the early years of the 20th century. This finding was first criticized by Ward and Devereux (2003), who argued, based on alternative measures of PPP-adjusted benchmarks between 1870 and 1930, that the United States was already leading the United Kingdom in terms of GDP per capita in the 1870s. This conclusion was criticized by Broadberry (2003).

New evidence, however, suggests a more complex picture: in the 18th century, real incomes in the US (settler colonies only, not including indigenous populations) were probably higher than those in the UK (Lindert & Williamson, 2016a). Until about 1870, growth was both exten- sive (incorporating newly settled territory) and intensive (considering the growth of cities and industry at the east coast), but on balance, the US may—in terms of real income—have lagged behind the UK. After 1870, intensive growth becomes more important, and the US slowly gets the upper hand. This pattern is consistent with direct benchmark comparison of the income of both countries for the period 1907–1909 (Woltjer, 2015). This shows that GDP per capita for the United States in those years was 26% higher than in the United Kingdom. We have used Woltjer’s (2015) benchmark to correct the GDP series of the two countries. Projecting this benchmark into the 19th century with the series of GDP per capita of both countries results in the two countries achieving parity in 1880. This is close to Prados de la Escosura’s conjecture based on his short- cut method (Prados de la Escosura, 2000), and even closer to the Lindert and Williamson (2016a) results.

Changing the US/UK ratio on the basis of the new research by Woltjer (2015) raises the question of which country’s GDP estimates should be adapted. In the current PWT approach, the growth of GDP per capita in the United States is the anchor for the entire system. For the 19th century, however, it is more logical to take the United Kingdom as the anchor, because it was the productivity leader, and because most research focused on creating historical benchmarks takes the United Kingdom as reference point. We have therefore adapted the UK series for the period 1908–1950 to fit the 1907–09 (Woltjer, 2015) benchmark in our view the best available benchmark for this period. The reason is that there are doubts about the accuracy of price changes and deflators for the UK for the period 1908–1950, given that it was characterized by two significant waves of inflation (during the two World Wars) and by large swings in relative prices and exchange rates (as documented in the detailed analysis by Stohr (2016) for Switzerland). Future research will have to assess whether this choice is justified.

This new version of the MPD extends GDP per capita series to 2022 and includes all new historical estimates of GDP per capita over time that have become available since the 2013 update (Bolt & Van Zanden, 2014). As new work on historical national accounts appears regularly, a frequent update to include new work is important, as it provides us with new insights in long-term global development. Furthermore, we have incorporated all available annual estimates for the pre-1820 period instead of estimates per half-century, as was usual in the previous datasets.

A general “warning” is in place here. For the period before 1900 (and for parts of the world such as Sub-Saharan Africa before 1950), there are no official statistics that fully cover the various components of GDP; and the more one moves back in time, the more a scarcity of basic statistics becomes a problem for scholars trying to chart the development of real income and output. The statistics needed for reconstructing GDP are often produced in parallel to the process of state formation, but even large bureaucratic states such as China or the Ottoman Empire only rarely collected the data that allow us to estimate levels of output and income. Much of the work on pre-industrial economies makes use of the “indirect method,” which links data on real wages and levels of urbanization to estimates of GDP per capita. But a few countries, during the Medieval and Early Modern periods, did collect the (tax) data to estimate GDP in the “proper” way (Tuscany in 1427, Holland in 1514, and England in 1086). These benchmarks, in combination with the many “indirect” estimates, allow us to create a tapestry of estimates which becomes—with the increase of the number of studies—increasingly robust. Where the original Maddison dataset included 158 observations for the pre 1820 period, the current 2023 MPD includes close to 2800 data points for the preindustrial period.

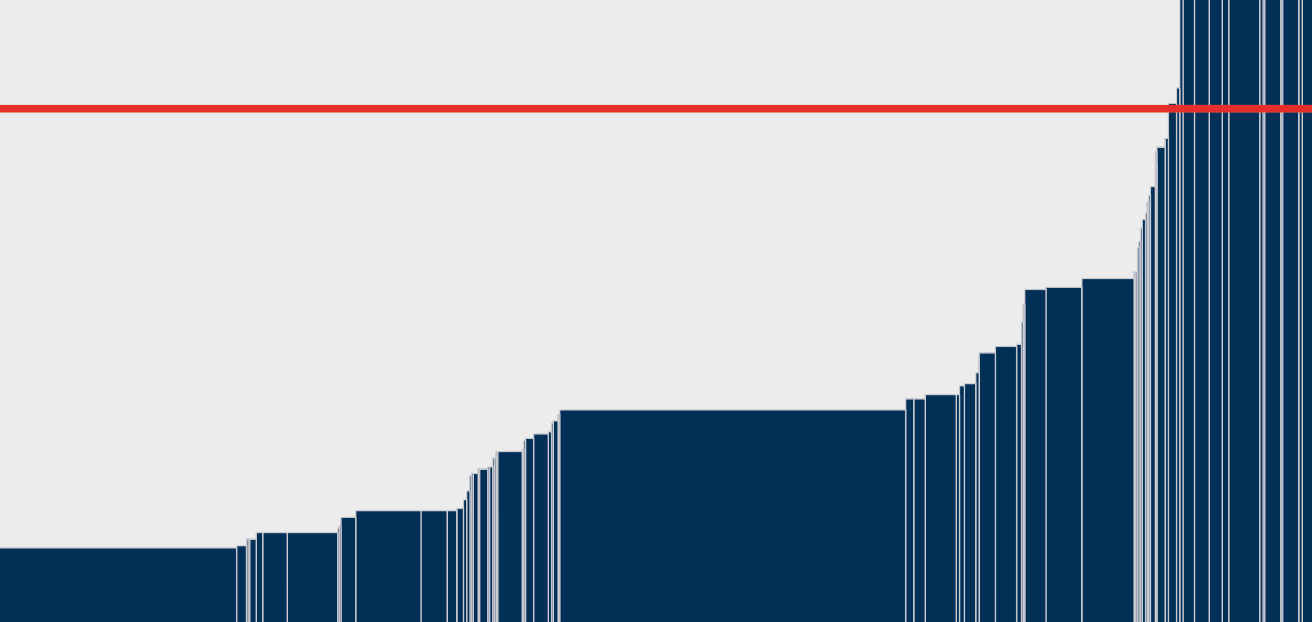

For the recent period, the most important new work is Harry Wu’s reconstruction of Chinese economic growth since 1950. Inspired by Maddison, Wu’s model produces state of the art estimates of GDP and its components for this important modern economy (Wu, 2014). Given the large role China plays in any reconstruction of global inequality, this is a major addition to the dataset. Moreover, as we will see below, Wu’s revised estimates of annual growth are generally lower than the official estimates. Lower growth rates between 1952 and the present, however, substantially increases the estimates of the absolute level of Chinese GDP in the 1950s (given the fact that the absolute level is determined by a benchmark in 1990 or 2011). This helps to solve a problem that arises in switching from the 1990 to the 2011 benchmark: namely, that when using the official growth estimates, the estimated levels of GDP per capita between 1890 and the early 1950s are substantially below subsistence level, and therefore too low. Including the new series as constructed by Wu (2014) gives a much more plausible long-run series for China.

Often, studies producing very early per capita GDP estimates—particularly work on the early modern period (1500–1800)—make use of indirect methods. The “model” or framework for making such estimates is based on the relationship between real wages, the demand for foodstuffs, and agricultural output (Álvarez-Nogal & De La Escosura, 2013; Malanima, 2011 among others). This model has now also been applied to Poland (Malinowski & van Zanden, 2017), Spanish America (Abad & van Zanden, 2016), and France (Ridolfi, 2017; Ridolfi & Nuvolari, 2021). In this update, we have now included annual estimates of GDP per capita in the period before 1800 for these countries.

For some countries during a period before 1870 or 1800, we only have series of a certain province or similar entity. The British series links to estimates for only England for the period before 1700; the series for the Netherlands links to estimates for only Holland for the period before 1807. The switch from the national to the “partial” series is clearly indicated in the dataset, and the “correction” in terms of GDP per capita is indicated.

Finally, we have extended the national income estimates up to 2022 for all countries in the database. For this we use various sources. The most important is the Total Economy Database (TED) published by the Conference Board, which includes GDP per capita estimates for a large majority of the countries included in the Maddison Project Database. The 2013 MPD update took the same approach (Bolt & van Zanden, 2014). For countries unavailable through TED, we relied on UN national accounts estimates to extend the GDP per capita series. To extend the population estimates up to 2022, we used the TED and the US Census Bureau’s International Database 2022.18 The TED revised their China estimates from 1950 onwards based on Wu (2014). As discussed above, we also included Wu (2014)’s new estimates in this update. Finally, we have extended the series for the former Czechoslovakia, the former Soviet Union, and former Yugoslavia, based on GDP and population data for their successor states.