Is income inequality rising around the world?

Whether inequality is rising or falling depends on where, when, and what aspect of inequality we have in mind.

Note: Since the publication of this article, the World Bank has updated its poverty and inequality data. See the note at the end for more information.

Rising levels of inequality has become a key political issue in recent years; "the defining issue of our time," as Barack Obama described it back in 2013. It was at the heart of the Occupy movement protests, and has received a huge amount of attention in the media and in policy circles. But much of this discussion has focussed on what's been happening in rich countries, in particular upon trends seen in the US. We tend to hear less about inequality in the rest of the world.

How has income inequality within countries been changing around the world more generally?

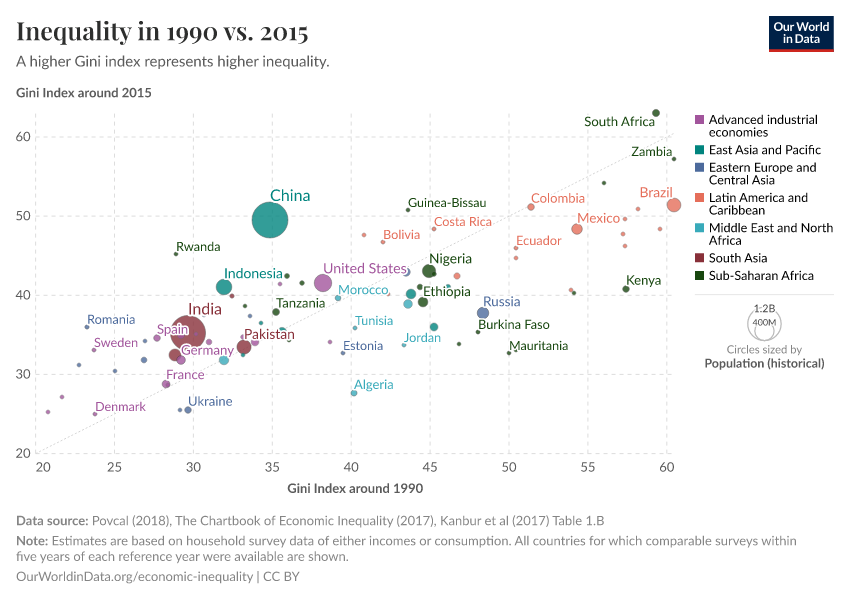

To answer this question, we brought together estimates of income inequality for two points in time: today and a generation ago in 1990. Our metric of income inequality is the Gini index which is higher in a country with higher inequality.1

We rely on estimates from two online databases: PovcalNet2, run by the World Bank, and the Chartbook of Economic Inequality, which I published together with Tony Atkinson, Salvatore Morelli, and Max Roser.3 This gave us a sample of 83 countries, covering around 85% of the world's population (download the data here).

The chart here compares levels of inequality today with those one generation ago. If you've not seen this sort of chart before, it may take a moment to understand what's going on. How high a country is in the chart shows you the level of inequality in 2015. How far to the right shows you the level of inequality in 1990.4 In addition, a 45-degree line is plotted. Countries below this line saw a fall in the Gini index between the two dates; countries above saw an increase.

Five observations on inequality across the globe

So what does the chart tell us about inequality within countries across the world?

No general trend to higher inequality

It's a mistake to think that inequality is rising everywhere. Over the last 25 years, inequality has gone up in many countries and has fallen in many others. It's important to know this. It shows that rising inequality is not ubiquitous nor inevitable in the face of globalization and suggests that politics and policy at the level of individual countries can make a difference.

Note the diversity between countries

As well as there being different trends, notice how very different the level of inequality is across countries. The spread you see – from the highest inequality countries in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, to the lowest-inequality countries in Scandinavia – is much larger than the changes in individual countries over this period.

There are clear regional patterns

To bring this out in the chart you can highlight particular regions by clicking on the labels in the chart’s legend.

- Almost all Latin American and Caribbean countries show very high levels of inequality but considerable declines from 1990 to 2015.

- Conversely, advanced industrial economies show lower levels of inequality but rises in most, though not all, instances.

- A number of Eastern European countries experienced rising inequality as they transitioned from socialist regimes.5

- We mostly see falls across the six countries in our sample from the Middle East and North Africa region. In Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia and the Pacific, the trends are more mixed.

Across countries, the average level of inequality has not changed

- The rises and falls seen in the Gini index in different countries more or less cancel out, the average Gini across countries fell marginally from 39.6 to 38.6.

- There were rises in inequality in some of the world's most populous countries, including China, India, the US and Indonesia (together accounting for around 45% of world population). As a result, if we weight countries according to the size of their population, we see that this weighted average Gini index increased by four percentage points, from 36.7 to 40.8.

- This means that, whilst in terms of the average country the Gini index stayed roughly constant across the two periods, the average person lived in a country that saw rising inequality.

Levels of inequality are converging

Interestingly, the chart shows that there was some convergence in inequality levels across countries over the last 25 years. Amongst those countries with a Gini index below 40 in 1990 (left half of the chart), hardly any saw substantial falls to 2015. Amongst those with a Gini index above 40 in 1990 (right half of the chart), hardly any saw substantial rises. As already pointed out, this apparent convergence works largely through regional dynamics. That said, those countries in our sample from Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia and Pacific regions are more evenly split between rising and falling levels of inequality but still roughly fit this convergent pattern.6

Conclusion

The Gini index is just one of the many ways we can measure inequality, each with its own pros and cons. You can read more about this in the 'Further notes' section below, as well as in our entry on economic inequality.

Nevertheless, it is clear from the chart we cannot make generalizations about inequality across the globe based on what we see in rich countries. Nor should we limit ourselves to thinking inequality must either be going up or going down, full stop. Posing the question in such a polarized way precludes a meaningful answer. Whether inequality is rising or falling depends on where, when, and what aspect of inequality we have in mind.

But this is very important to know in itself. It shows us that rising inequality is not just an inevitable outcome of global economic forces completely beyond our control. National institutions, politics, and policy play a key role in shaping how these forces impact incomes across the distribution. Being attentive to the differences between countries is an important step in knowing what can be done to reduce inequality.

The World Bank has updated its poverty and inequality data since the publication of this article

This article uses a previous release of the World Bank's poverty and inequality data. Explore the latest data on our Inequality Data Explorer.

Endnotes

Whilst we refer to 'income inequality' here, the estimates in the chart are based upon household surveys of both income and consumption, depending on the country. This is discussed more in the 'Further notes' section below.

PovcalNet data is currently available in the World Bank Poverty and Inequality Platform

For China, we take the series presented in table 1.B from Kanbur, R, Y Wang and X Zhang (2017) "The great Chinese inequality turnaround", CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11892.

The estimates are based on household surveys of either income or consumption. This heterogeneity, as well as that between varying definitions of income and survey methodologies used, introduces important inconsistencies that may affect the levels or trends seen across countries. See "Further notes" below.

Given that estimates are not available for every year, we selected those falling closest to 1990 and 2015, up to a maximum of 5 years' distance.

The full-time series of estimates for these countries shows that the rises were mostly concentrated in the immediate post-Soviet period in the 1990s.

Amongst OECD countries, Noland et al. (2017) note, in general, larger rises in inequality since 1980 in those countries beginning from a lower starting point. "Inequality and Prosperity in the Industrialised World". CitiGPS: Global Perspectives & Solutions. September 2017.

Alvaredo and Gasparini (2013) settle on a downward adjustment of around 15 percent to Latin American and Caribbean estimates in their analysis of the Povcal data. This means a Gini index of 50 is reduced to around 43. They base the figure on the average difference between income and consumption Gini estimates for those years and countries (within Latin America and the Caribbean) in which both were available.

Of the 14 countries in the WID data that saw a rise in the Gini index of more than 2 percentage points, three countries saw a fall in the top 1% income share, of which only one – Cote d'Ivoire – saw a fall greater than half a percentage point.

Hoy, C. "Leaving No One Behind: the Impact of Pro-Poor Growth". ODI Report. October 2015.

Absolute inequality measures capture increases in absolute rather than relative differences between people's incomes. If the average income of the top 10% is $100,000 and the average income of the bottom 10% is $10,000, then the absolute difference between the groups is $90,000. Doubling everyone's income would not increase relative inequality, but it would increase absolute inequality.

There have been a small number of surveys involving university students about this question. In each case, about half of the respondents showed they thought about inequality in absolute terms. Martin Ravallion summarises these studies in Ravallion, M. (2014). Income Inequality in the Developing World. Science (New York, N.Y.). 344. 851-5. 10.1126/science.1251875

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Joe Hasell (2018) - “Is income inequality rising around the world?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/income-inequality-since-1990.html' [Online Resource] (archived on March 4, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-income-inequality-since-1990,

author = {Joe Hasell},

title = {Is income inequality rising around the world?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2018},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/income-inequality-since-1990.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.