Light at Night

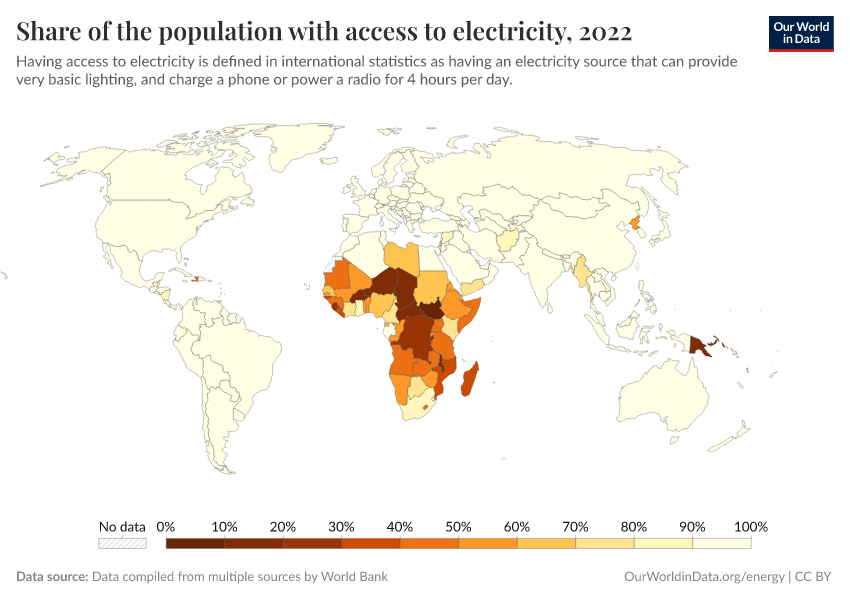

Light at night was once expensive everywhere. In some places people are still lacking light at night, while in other places light became extremely cheap.

Being able to switch on the light at night is something that most people today take for granted. But for those that live, or have lived where there is no artificial light, you can appreciate how important it is. After sunset, working, reading, and many other aspects of living become impossible.

Unfortunately, this is still the reality for many people today, and it was the default for everyone in the past.

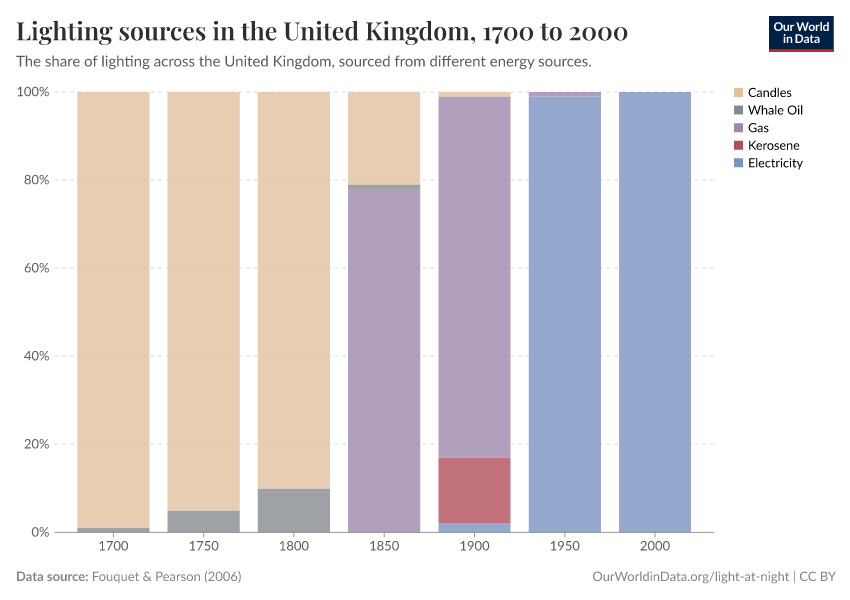

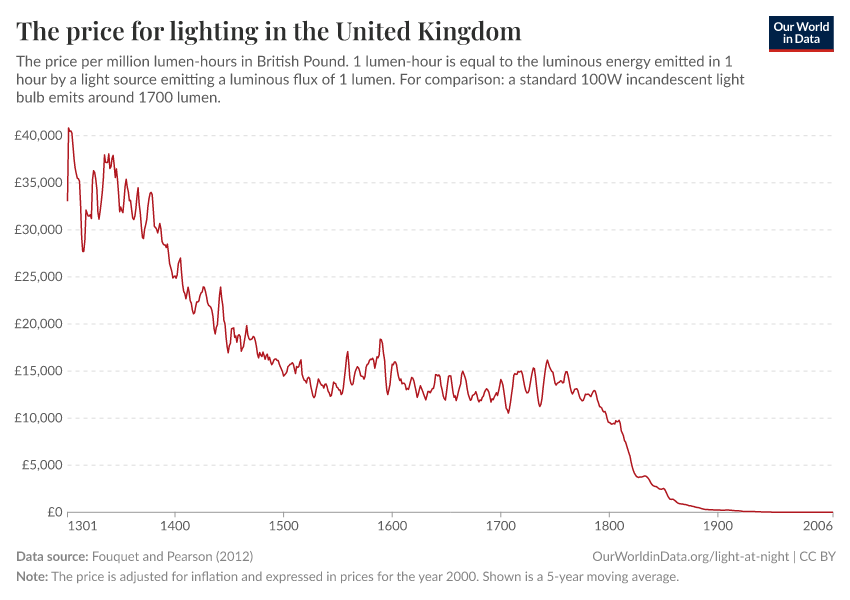

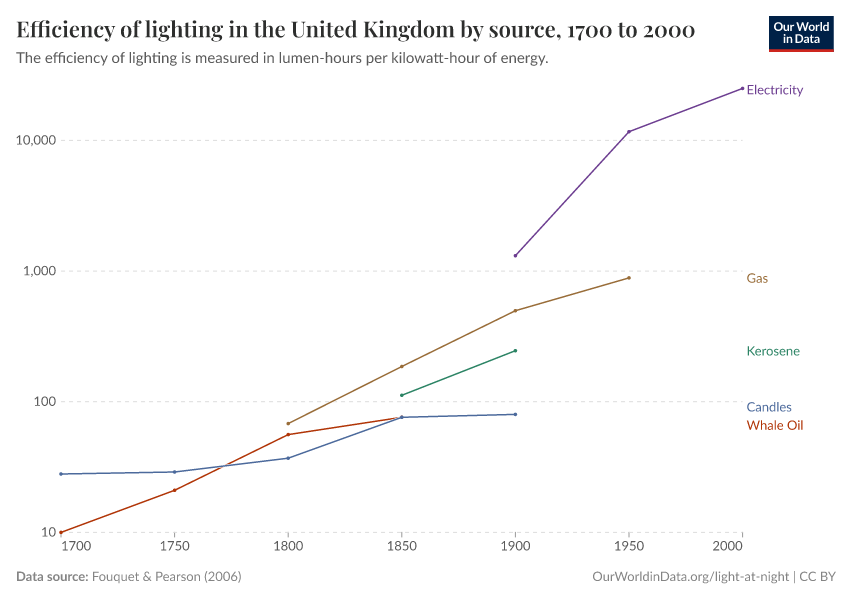

By following the history of the light — the transitions from candles to lamps to lightbulbs — and the developments that make these accessible, we can learn a lot about technological innovation and economic changes over the centuries.

The price of light has fallen by more than 99.9% since 1700. And its efficiency has increased 1000-fold. This has made light at night available to more and more people.

On this page, you can find data, visualizations, and writing about changes in efficiency, price, and access to lighting.

Research & Writing

The world's energy problem

The world faces two energy problems: most of our energy production still produces greenhouse gas emissions, and hundreds of millions lack access to energy entirely.

Global whaling peaked in the 1960s

Intense whaling for light and oil drove many of the world’s whale species close to extinction. But a dramatic decline in whale hunting since then has given them hopes of recovery.

Key Charts on Light at Night

See all charts on this topicEndnotes

Fouquet, R. (2026). A Historical Perspective on Energy Innovation: Energy Transitions, Efficiency Improvements, Rebound Effects and Consumer Welfare Impacts in Anadon, L.D., Sagar, A., Verdolini, E., and Malhotra, A. (ed.) Handbook on Energy Innovation. Edward Elgar Publications. Cheltenham, UK, and Northampton, MA, USA. and Fouquet, R., & Pearson, P. J. (2006). Seven centuries of energy services: The price and use of light in the United Kingdom (1300-2000). The energy journal, 27(1).

Fouquet, R., & Pearson, P. J. (2006). Seven centuries of energy services: The price and use of light in the United Kingdom (1300-2000). The energy journal, 27(1).

Fouquet, R., & Pearson, P. J. (2006). Seven centuries of energy services: The price and use of light in the United Kingdom (1300-2000). The Energy Journal, 27(1).

Several papers have shown that light density at night reflects standards of living well, both across geographic regions and across time. Some of these papers are:

Christopher Small & Christopher D. Elvidge (2013) – Night on Earth: Mapping decadal changes of anthropogenic night light in Asia. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation. Volume 22, June 2013, Pages 40–52. Online here.

Henderson, Storeygard, and Weil (2011) – “Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space,” American Economic Review, 102(2), 994-1028. This paper is online here.

Chen and Nordhaus (2011) – “Using Luminosity Data as a Proxy for Economic Statistics,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(21), 8589—8594.

Tilottama Ghosh, Rebecca L. Powell, Christopher D. Elvidge, Kimberly E. Baugh, Paul C. Sutton and Sharolyn Anderson (2010) – Shedding Light on the Global Distribution of Economic Activity. The Open Geography Journal, 2010, 3, 147-160 147.

Maxim Pinkovskiy and Xavier Sala-i-Martin (2016) – Lights, Camera … Income! Illuminating the National Accounts-Household Surveys Debate. The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2016) 131 (2): 579-631. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjw003 Online at http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/content/131/2/579.full?etoc.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Arriagada, and Bertha Rohenkohl (2023) - “Light at Night” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/light-at-night' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-light-at-night,

author = {Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie and Pablo Arriagada and Bertha Rohenkohl},

title = {Light at Night},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/light-at-night}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.