The ‘Varieties of Democracy’ data: how do researchers measure democracy?

There are many ways to measure democracy. Here is how the Varieties of Democracy project — one of the leading sources of global democracy data — does it.

Measuring the state of democracy across the world helps us understand the extent to which people have political rights and freedoms.

But measuring democracy comes with many challenges. People do not always agree on what characteristics define a democracy. These characteristics — such as whether an election was free and fair — are difficult to define and assess. The judgment of experts is to some degree subjective. They may disagree about a specific characteristic or how something as complex as a political system can be reduced into a single measure.

How do researchers address these challenges and measure democracy?

What is the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project?

In some of our work on democracy, we rely on data published by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project.1

The project is managed by the V-Dem Institute, based at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. It spans seven more regional centers around the world and is run by five principal investigators, dozens of project and regional managers, and more than 100 country coordinators.

V-Dem is funded through grants and donations by government agencies and private foundations, such as the Swedish Research Council, the European Commission, and the Marcus and Marianne Wallenberg Foundation.

How does V-Dem characterize democracy?

True to its name, the Varieties of Democracy project acknowledges that democracy can be characterized differently, and measures electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian characterizations of democracy.

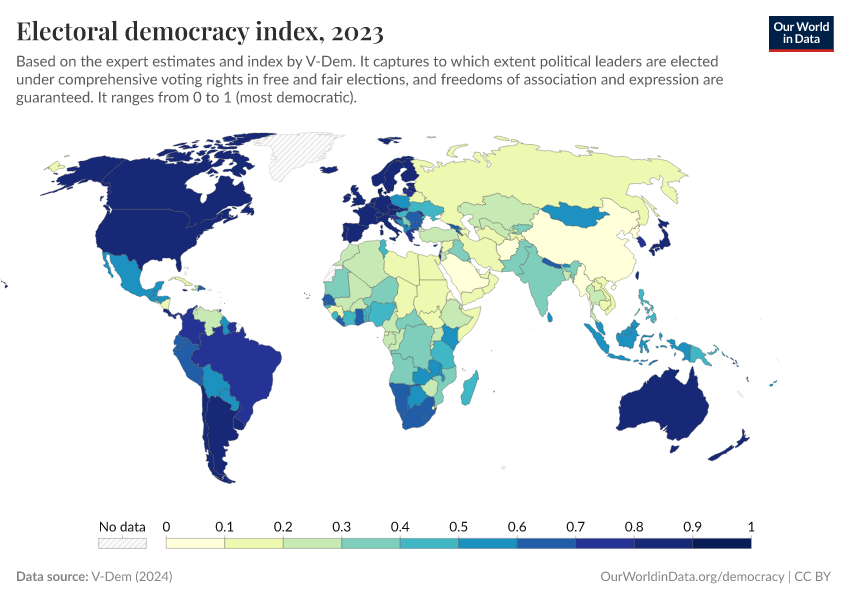

At Our World in Data we primarily use V-Dem’s Electoral Democracy Index to measure democracy.2 The index is used in all of V-Dem’s other democracy indices because V-Dem considers there to be no democracy without elections. The other aspects can therefore be thought of as measuring the quality of a democracy.

V-Dem characterizes electoral democracy as a political system in which political leaders are elected under comprehensive voting rights in free and fair elections, and freedoms of association and expression are guaranteed. More specifically, this means:

- Elected political leaders: broad elections choose the chief executive and legislature

- Comprehensive voting rights: all adult citizens have the legal right to vote in national elections

- Free and fair elections: no election violence, government intimidation, fraud, large irregularities, and vote buying

- Freedom of association: parties and civil society organizations can form and operate freely

- Freedom of expression: people can voice their views and the media can present different political perspectives

You can find data on the other democracy indices, the different characteristics of electoral democracy, and other derived measures in our Democracy Data Explorer.

How is democracy scored?

The Electoral Democracy Index scores each country on a spectrum, with some countries being more democratic than others.

The spectrum ranges from 0 (‘highly undemocratic’) to 1 (‘highly democratic’).

This scoring thereby differs from other approaches such as ‘Regimes of the World’ and others, which classify countries as a binary: either they are a democracy or not.

What years and countries are covered?

As of version 15 of the dataset, V-Dem covers 202 countries, going back in time as far as 1789. Many countries have been covered since 1900, including before they became independent from their colonial powers.

How is democracy measured?

How does V-Dem work to make its assessments valid?

To actually measure what it wants to capture, V-Dem assesses the characteristics of democracy mostly through evaluations by experts.3

These anonymous experts are primarily academics and members of the media and civil society. They are also often nationals or residents of the country they assess, and therefore know its political system well and can evaluate aspects that are difficult to observe.

V-Dem’s own team of researchers supplements the expert evaluations. They code some easier-to-observe rules and laws of the political system, such as whether the legislature has a lower and upper house.

How does V-Dem work to make its assessments precise and reliable?

V-Dem uses several experts per country, year, and topic, to make its assessments less subjective. In total, V-Dem relies on more than 4,000 country experts.

While there are fewer experts for small countries and for the time before 1900, they rely typically on 25 experts per country and 5 experts per topic.

How does V-Dem work to make its assessments comparable?

V-Dem also works to make their coders’ assessments comparable across countries and time.

The surveys ask the experts to answer very specific questions on completely explained scales about sub-characteristics of political systems — such as the presence or absence of election fraud — instead of making them rely on their broad impressions.

The surveys are available in English, Arabic, French, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish to reduce misunderstandings.

Experts further evaluate hypothetical countries, many of them coded several countries, and they denote their own uncertainty and personal demographic information.

V-Dem then uses this information to investigate expert biases, which they have found to be limited: they only find that experts from a country tend to be stricter in their assessments. 4

How are the remaining differences in the data dealt with?

V-Dem uses a statistical model to address any remaining differences between coders.5

The model combines the experts’ ratings of actual countries and hypothetical countries, as well as the experts’ stated uncertainties and personal demographics to produce best, upper-, and lower-bound estimates of many characteristics.6

V-Dem provides these different estimates for all of its main and supplementary indices, including the Electoral Democracy Index and the subindices for free and fair elections, freedom of association, and freedom of expression.

With the different estimates, V-Dem explicitly acknowledges that its coders can be uncertain or make errors in their measurement.

The overall Electoral Democracy Index score is the result of weighing, multiplying, and adding up the subindices.7

The subindices are weighted because V-Dem considers some of them as more important than others: elected officials and voting rights are weighted less because they capture more formal requirements, as opposed to free and fair elections and the freedoms of association and expression that rely more on expert assessments.

The subindices are partially multiplied and partially added up because V-Dem wants the subindices to partially compensate for one another, and partially for them to reinforce each other. An example of compensation is voting rights partially making up for a lack of rights to assemble and protest, whereas an example of reinforcement is voting rights mattering more if voters can also choose opposition candidates.

How is the data made accessible and transparent?

V-Dem releases its data publicly, and makes it straightforward to download and use.

It publishes the overall scores, the underlying subindices, and several hundred specific questions by country-year, country-date, and coder.

V-Dem also releases detailed descriptions of how they characterize democracy, the questions and coding procedures that guide the experts and researchers, as well as why it weighs, adds, and multiplies the scores for specific characteristics.

How do we change the data?

In our work, we expand the years covered by V-Dem further.

To expand the time coverage of today’s countries and include more of the period when they were still non-sovereign territories, we identified the historical entity they were a part of and used that regime’s data whenever available.8

We also calculated regional and global averages of the Electoral Democracy Index and its sub-indices, weighted and unweighted by population.

How often and when is the data updated?

V-Dem releases a new version of the data each year in March.

We at Our World in Data aim to update our own data within a few weeks of the release.

What are the data’s shortcomings?

There are shortcomings in the way the Electoral Democracy Index characterizes and measures democracy.9

The index focuses on an electoral understanding of democracy and does not account for other characterizations, such as democracies as egalitarian political systems, in which political power is equally distributed to allow everyone to participate. This means that some of the most economically-unequal countries in the world, such as Brazil and South Africa, are classified as broadly democratic in recent years.10

V-Dem also does not cover some countries with very small populations.

Furthermore, the index is more difficult to interpret than other measures. Measures that group countries into democracies and autocracies, such as the Regimes of the World classification, make it possible to say which country was a democracy.

The Electoral Democracy Index makes no clear assessment there, and only allows us to say whether a country is relatively democratic by comparing it to the range of the index, to other countries, or to the same country at another point in time. And when doing so, it is still difficult to say how large these differences are.11

The assessment of the Electoral Democracy Index remains to some extent subjective. Its index is built on difficult evaluations by experts that rely less on easier-to-observe characteristics, such as whether regular elections are held.

Finally, the index’s aggregation remains to some extent arbitrary. It is unclear why these specific subindices were chosen; and why two subindices, elected officials and voting rights, are weighted less than the others.

What are the data’s strengths?

Despite these shortcomings, the index tells us a lot about how democratic the world was in the past and today.

Its characterization of democracy as an electoral political system, in which citizens get to participate in free and fair elections, is commonly recognized as the basic principle of democracy and shared by all of the leading approaches of measuring democracy.

Because it treats democracy as a spectrum, the index is able to capture both big and small differences in the political systems of countries, and to record small changes within countries over time. This allows us to observe whether one country is more democratic than another, or whether a country has become more or less democratic over time.

The index also covers many countries and years. With the exception of microstates, it covers all countries in the world. Many countries are covered since 1900 — even while they were colonized by another country — and some of them as far back as 1789.

Finally, V-Dem takes many steps to make its assessments valid, precise, comparable across countries and time, and transparent. It relies on many country and subject experts answering detailed surveys to measure aspects of political systems that are often difficult to observe and acknowledges the remaining uncertainty in their assessments.

What is our summary assessment?

Whether V-Dem’s Electoral Democracy Index is a useful measure of democracy will depend on the questions we want to answer.

The index will not give us a satisfying answer if we are interested in non-electoral understandings of democracy (or different understandings of electoral democracy); if we are also interested in the political systems of microstates; and only interested in big differences in the political systems of countries.

In these cases, we will have to rely on other measures.

But if we value a sophisticated measure based on the knowledge of many country experts and are interested in big and small differences in electoral democracy, within and across countries, and far into the past, we can learn a lot from this data.

It is for these latter purposes we use the measure in some of our reporting on democracy.

Keep reading on Our World in Data

Acknowledgments

I thank Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, and Max Roser for their very helpful comments and ideas about how to improve this article.

Endnotes

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Fabio Angiolillo, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Linnea Fox, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Ana Good God, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Joshua Krusell, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Natalia Natsika, Anja Neundorf, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Marcus Tannenberg, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Felix Wiebrecht, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2025. "V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v15" Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von Römer. 2025. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data”. V-Dem Working Paper No. 21. 10th edition. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

The index is sometimes also called the Polyarchy Index.

For more details, see: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan Lindberg, Jan Teorell, Kyle Marquardt, Juraj Medzihorsky, Daniel Pemstein, Nazifa Alizada, Lisa Gastaldi, Garry Hindle, Josefine Pernes, Johannes von Römer, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, and Steven Wilson. 2021. V-Dem Methodology v11.1. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project: page 24.

“We have run extensive tests on how well such individual-level factors predict country-ratings but have found that the only factor consistently associated with country-ratings is country of origin (with “domestic” experts being harsher in their judgments).”

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan Lindberg, Jan Teorell, Kyle Marquardt, Juraj Medzihorsky, Daniel Pemstein, Nazifa Alizada, Lisa Gastaldi, Garry Hindle, Josefine Pernes, Johannes von Römer, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, and Steven Wilson. 2021. V-Dem Methodology v11.1. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project: page 24.

Specifically, it uses a Bayesian Item-Response Theory estimation strategy.

Marquardt, Kyle, and Daniel Pemstein. 2018. IRT Models for Expert-Coded Panel Data. Political Analysis 26(4): 431-456.

Expressed precisely, V-Dem’s measurement model produces a probability distribution over the country-year scores. The best estimate is the distribution’s median, while the upper and lower bound estimates demarcate the interval in which the model places 68 percent of the probability mass.

The precise formula is:

electoral democracy index = 0.5 * multiplicative polyarchy index + 0.5 * additive polyarchy index; with

multiplicative polyarchy index = elected officials * free and fair elections * comprehensive suffrage * freedom of association * freedom of expression; and

additive polyarchy index = 0.125 * elected officials + 0.25 * free and fair elections + 0.125 * comprehensive suffrage + 0.25 * freedom of association + 0.25 * freedom of expression

For example, V-Dem only provides regime data since Bangladesh’s independence in 1971. There is, however, regime data for Pakistan and the colony of India, both of which the current territory of Bangladesh was a part. We, therefore, use the regime data of Pakistan for Bangladesh from 1947 to 1970, and the regime data of India from 1789 to 1946. We did so for all countries with a past or current population of more than one million.

This and the following section draw on several very helpful other articles summarizing and reviewing some of the leading democracy datasets:

Boese, Vanessa. 2019. How (not) to measure democracy. International Area Studies Review 22(2): 95-127.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Staffan I. Lindberg, Svend-Erik Skaaning, and Jan Teorell. 2017. V-Dem Comparisons and Contrasts with Other Measurement Projects. V-Dem Working Paper 45.

Møller, Jørgen and Svend-Erik Skaaning. 2021. Varieties of Measurement: A Comparative Assessment of Relatively New Democracy Ratings based on Original Data. V-Dem Working Paper 123.

Skaaning, Svend-Erik. 2018. Different Types of Data and the Validity of Democracy Measures. Politics and Governance 6(1): 105-116.

True to its name, however, V-Dem provides several democracy indices in addition to the Electoral Democracy Index, and also measures liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian characterizations of democracy.

This can be made easier by comparing how a score relates to the index’s overall distribution or its distribution for a specific year.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Bastian Herre (2022) - “The ‘Varieties of Democracy’ data: how do researchers measure democracy?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260128-100359/vdem-electoral-democracy-data.html' [Online Resource] (archived on January 28, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-vdem-electoral-democracy-data,

author = {Bastian Herre},

title = {The ‘Varieties of Democracy’ data: how do researchers measure democracy?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260128-100359/vdem-electoral-democracy-data.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.