Democracy data: how sources differ and when to use which one

There are many ways to classify and measure political systems. What approaches do different sources take? And when is which approach best?

Measuring the state of democracy across the world helps us understand the extent to which people have political rights and freedoms.

But measuring how democratic a country is, comes with many challenges. People do not always agree on what characteristics define a democracy. These characteristics — such as whether an election was free and fair — even once defined, are difficult to assess. The judgement of experts is to some degree subjective and they may disagree; either about a specific characteristic, or how several characteristics can be reduced into a single measure of democracy.

So how do researchers address these challenges and identify which countries are democratic and undemocratic?

In our work on Democracy, we provide data from seven leading approaches of measuring democracy:

- Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) by the V-Dem project1

- Regimes of the World (RoW) by Lührmann et al. (2018)2, which use V-Dem data

- Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED) by Skaaning et al. (2015)3

- Freedom House’s (FH) Freedom in the World4

- Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) by the Bertelsmann Foundation5

- Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index6

- Polity by the Center for Systemic Peace7

These approaches all measure democracy (or a closely related aspect), they cover many countries and years, and are commonly used by researchers and policymakers.

You can delve into their data — the main democracy measures, indicators of specific characteristics, and global and regional overviews — in our Democracy Data Explorer.

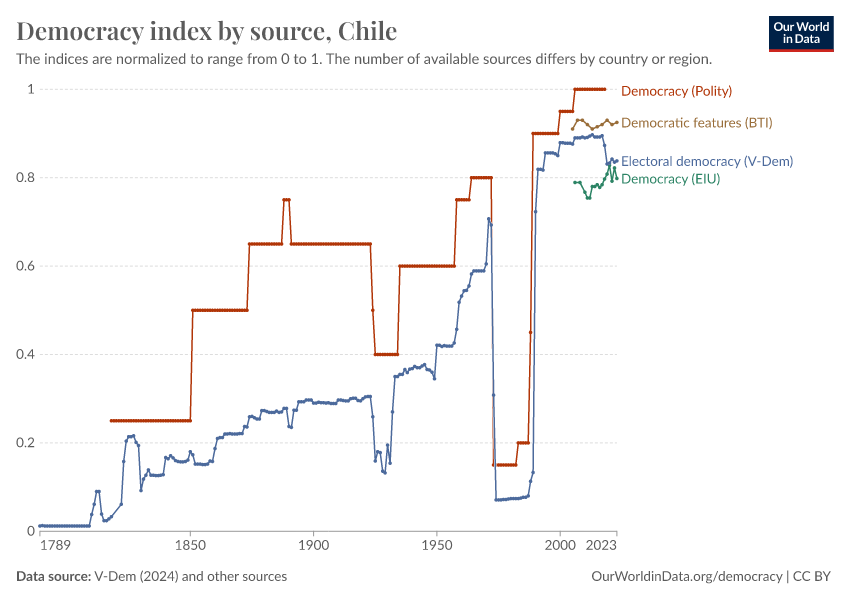

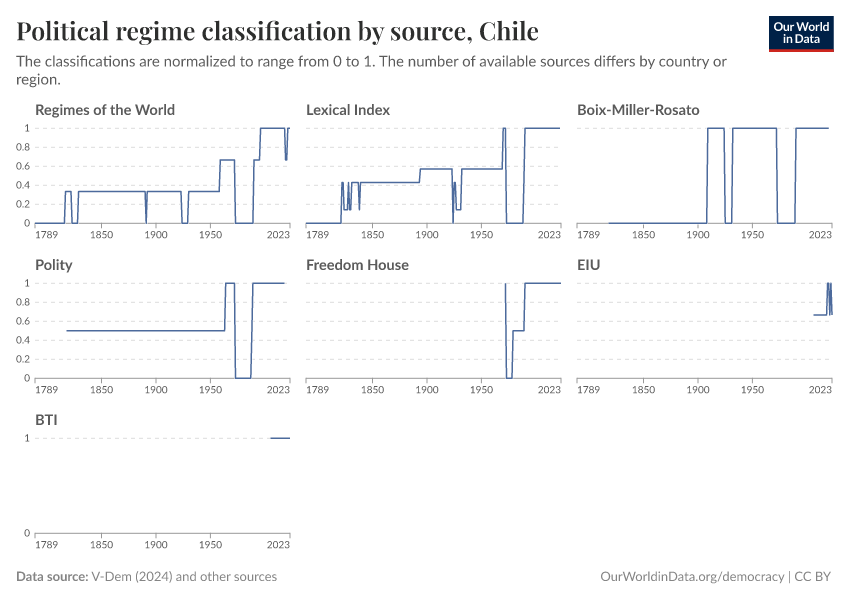

Reassuringly, the approaches typically agree about big differences in countries’ political institutions: they readily distinguish between highly democratic countries, such as Chile and Norway, and highly undemocratic countries, such as North Korea and Saudi Arabia.

But they do not always agree. They come to different assessments about which of two highly democratic countries – Denmark and Norway – is more democratic, and whether Chile is more or less democratic than it was ten years ago. At times they come to significantly different conclusions about countries, such as Nigeria today or the United States in the 19th century.

Why do these measures sometimes reach such different conclusions? In this article I summarize the key similarities and differences of these approaches, and discuss when each source is best.

How is democracy characterized?

In this and the following tables I summarize how each approach defines and scores democracy, and what coverage each approach provides.8

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

We see that the approaches share a basic principle of democracy: a democracy is an electoral political system in which citizens get to participate in free and fair elections. The approaches also mostly agree that democracies are liberal political systems, in which citizens have additional civil rights and are protected from the state by constraining it.

Some approaches stop there, and stick to these narrower conceptions of democracy. Others characterize democracy in broader terms, and also see it as a participatory and deliberative (citizens engage in elections, civil society, and public discourse) as well as an effective (governments can act on citizens’ behalf) political system.

Varieties of Democracy — true to its name — offers both narrow and broader characterizations, by separately adding liberal, participatory, deliberative, as well as egalitarian (economic and social resources are equally distributed) political institutions to electoral democracy.

How is democracy scored?

The approaches also differ in how they score democracy.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

V-Dem treats democracy as a spectrum, with some countries being scored as more democratic than others.

Other approaches instead treat democracy as a binary, and classify a country as either a democracy or not.

A final group does both, using a spectrum of countries being more or less democratic, and setting thresholds above which a country is considered a democracy overall.

Approaches that classify countries into democracies and non-democracies further differ in whether all countries that are not democracies are considered autocracies or authoritarian regimes, or whether there are some countries that do not clearly belong in either group.

And while Freedom in the World identifies which countries are electoral democracies in recent years, its main classification distinguishes between free, partly-free, and not-free countries (which many treat as a proxy for liberal democracy).

Beyond these broad similarities in how the approaches characterize and score democracy, their exact definitions differ in smaller ways, too. If you are interested in the details, you can take a closer look at the specific defining characteristics at the end of this article.

What differences are captured?

How the approaches score democracy affects what differences in democracy they can capture.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

Classifications tend to be coarser, and therefore cover big to medium differences in democracy: they reduce the complexity of political systems a lot and distinguish between broad types, such as the democracies of Chile and Norway on the one hand, and the non-democracies of North Korea and Saudi Arabia, on the other.

The fine-grained spectrums of other approaches meanwhile reduce political systems’ complexity a bit less, and capture both big and small differences in democracy, such as the difference in democratic quality between the democracies Chile and Norway, and the difference between autocracies North Korea and Saudi Arabia. Spectrums can also better capture small changes within political systems over time, towards or away from democracy.

While some approaches use their classifications exclusively to reduce the complexity of their spectrums, others also use theirs to clearly define what features characterize each category.

What years and countries are covered?

The approaches also differ in what years and countries they cover.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

All approaches cover the recent past, but differ in how far they go back in time. BTI and EIU begin in the mid-2000s. Freedom in the World starts in the early 1970s. The other approaches go back to the beginning of the 19th century or even the late 18th century. The Regimes of the World data we ourselves extended back from 1900.

All approaches cover most countries in the world. They differ in how comprehensive their coverage is: BTI excludes long-term members of the OECD (which it considers consolidated democracies), while all other approaches assess them. Some approaches also include very small states and territories, and some also assess many non-independent countries, usually colonies.9

How are democracy’s characteristics assessed?

The approaches also differ in how they go about assessing the characteristics of democracy.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

Many rely on evaluations to assess democratic characteristics that are difficult to observe, such as whether elections were competitive and people were free to express their views.

Some rely on evaluations by country experts to assess whether, or to which extent, democracy’s characteristics are present (or not) in any given country and year. Others depend on evaluations by their own researchers reviewing the academic literature and news reports. And many use both country experts and their own teams.

A few additionally incorporate some representative surveys of regular citizens.

The Lexical Index meanwhile works to avoid difficult evaluations by either experts or researchers, and mostly has their own team assess easy-to-observe characteristics — such as whether regular elections are held and several parties compete in them — to identify (non-)democracies.

Depending on whether they score democracy as a spectrum or classification, the approaches then aggregate the scores for specific characteristics: some average, add, and/or weigh the scores, others assess whether necessary characteristics are present, and a few do both.

How do approaches work to make assessments valid?

The next tables summarize how the approaches address the challenges that come with measuring democracy. The first challenge is to make their assessments valid — to actually measure what they want to capture.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

The approaches go about measuring democracy differently because they weigh the challenges of measurement differently.

For those mostly relying on experts, the priority is that democracy’s characteristics are evaluated by people that know the country well. For those relying on their own researchers, the priority is that the coders know the approach’s characterization of democracy and the measurement procedures well. And for those relying on representative surveys, capturing the difficult-to-observe lived realities of regular citizens is especially important.

How do approaches work to make assessments precise?

The approaches are also concerned with making their assessments in a precise and reliable manner.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

Expert-based approaches therefore often recruit many experts in total, several experts per country, or even several to many experts per country, year and characteristic.

Own-researcher-based approaches instead either focus more on making difficult subjective evaluation mostly unnecessary, or encourage their teams to rely on many different secondary sources, such as country-specific academic research, news reports, and personal conversations.

How do approaches work to make assessments comparable?

The approaches also face the challenge of how to make the coders’ respective assessments comparable across countries and time.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

The surveys therefore ask the experts questions about specific characteristics of democracy, such as the presence or absence of election fraud, instead of making them rely on their broad impressions. They also explain the scales on which the characteristics are scored, and often all of the scales’ values.

Measuring many specific low-level characteristics also helps users understand why a country received a specific score, and it allows them to create new measures tailored to their own interests.

How are remaining differences dealt with?

The approaches then all work to address any remaining differences between coders, even if they do so differently.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

V-Dem and RoW work with a statistical model which uses the experts’ ratings of actual countries and hypothetical country examples, as well as the experts’ stated uncertainties and personal demographics to produce both best and upper- and lower-bound estimates of many characteristics.

They thereby avoid forcing themselves to eliminate all uncertainty and thereby possibly biasing their scores, and acknowledge that its coders make errors. This also recognizes that small differences in democracy on fine-grained spectrums may actually not exist, or be reversed, because measurement is uncertain.

Most other approaches go about it differently, and have researchers and experts discuss differing scores to reconcile them. This adds an additional step to make the assessments comparable across coders, countries, and years.

And while it uses discussions, Freedom in the World still acknowledges that it refined its approach over time, which makes its scores not as readily comparable: they work best for comparing different countries at the same time, or comparing the same country over the course of a few years.

The Lexical Index and Polity meanwhile do not have several coders per country and year, but they still worked to assess coding differences by once having its researchers rate some countries independently and compare their results. Reassuringly, they found that they came to similar conclusions.

How do approaches work to make data accessible and transparent?

Finally, the approaches all take steps to make their data accessible and the underlying measurement transparent.

| Varieties of Democracy |

|

| Regimes of the World |

|

| Lexical Index |

|

| Freedom House |

|

| Bertelsmann Transformation Index |

|

| Economist Intelligence Unit |

|

| Polity |

|

All approaches publicly release their data and almost all make the data straightforward to download and use. Most approaches release not only the overall classification and scores, but also the underlying (sub)characteristics. V-Dem even releases the data coded by each (anonymous) expert.

Almost all release descriptions of how they characterize democracy, as well as the questions and coding procedures guiding the experts and researchers. V-Dem again stands out here for its very detailed descriptions that also discuss why it weighs, adds, and multiplies the scores for specific characteristics.

Freedom in the World, BTI, and Polity meanwhile provide additional helpful information by explaining their quantitative scores in country reports that discuss influential events.

The best democracy measure depends on your questions

There is no single ‘best’ approach to measuring democracy. Conceptions of democracy are too different, and the challenges of measurement are too diverse for that. All of the approaches put a lot of effort into measuring democracy in ways that are useful to researchers, policymakers, and interested citizens.

The most appropriate democracy measure depends on what question you want to answer. It is the one that captures the characteristics of democracy and the countries and years you are interested in.

If you are interested in big and small differences in varieties of democracy, far into the past, and want to use country experts to measure characteristics of political systems that are difficult to observe, the Varieties of Democracy data is best.

If you are instead interested in big differences in political regimes over the last two hundred years, and want to use the knowledge of country experts, the Regimes of the World data is best.

If you rather want to explore medium differences in political regimes, especially in the 19th and earlier 20th century, and want to rely more on characteristics that are easier to observe, the Lexical Index is best.

If you instead want to explore the source that was researchers’ go-to for democracy for a long time, and are fine with its less precise data, Polity is best.

If you especially care about the political and civil freedoms that democracy grants, Freedom House is best.

If you value a broad understanding of democracy that encompasses its electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and effective dimensions, then the Bertelsmann Transformation Index is best.

And if you want to use a broad understanding of democracy to study it both in countries where it is older and those in which it is young or absent, then the Economist Intelligence Unit is best.

Even if you have a preferred source, it can still be useful to see what other sources show and where they agree and differ.

This means that having several approaches to measuring democracy is not a flaw, but a strength: it gives us different tools to understand the past spread, current state, and possible future of democracy around the world.

If you want to explore the data that each of these datasets produce, you can do so in our Democracy Data Explorer.

And if you want to compare the sources directly, you can do so in these charts:

Keep reading at Our World in Data

Acknowledgements

I thank Daniel Bachler, Hauke Hartmann, Joan Hoey, Staffan Lindberg, Michael K. Miller, Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Svend-Erik Skaaning for reading drafts of this text and their very helpful comments.

Endnotes

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Fabio Angiolillo, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Linnea Fox, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Ana Good God, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Joshua Krusell, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Natalia Natsika, Anja Neundorf, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Marcus Tannenberg, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Felix Wiebrecht, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2025. "V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v15" Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von Römer. 2025. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data”. V-Dem Working Paper No. 21. 10th edition. University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Lührmann, Anna, Marcus Tannnberg, and Staffan Lindberg. 2018. Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes. Politics and Governance 6(1): 60-77.

Skaaning, Svend-Erik, John Gerring, and Henrikas Bartusevičius. 2015. A Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy. Comparative Political Studies 48(12): 1491-1525.

Freedom House. 2025. Freedom in the World 2024.

Bertelsmann Foundation. 2024. Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2024.

Economist Intelligence Unit. 2025. Democracy Index 2024.

Marshall, Monty G. and Ted Robert Gurr. 2021. Polity 5: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018. Center for Systemic Peace.

This article draws on several very helpful other articles summarizing and reviewing some of the datasets, as well as the datasets’ own codebooks and descriptions:

Bertelsmann Foundation. 2022. BTI Codebook for Stata.

Boese, Vanessa. 2019. How (not) to measure democracy. International Area Studies Review 22(2): 95-127.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Eitan Tzelgov, Luca Uberti, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, and Daniel Ziblatt. 2022. V-Dem Codebook v12. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Staffan I. Lindberg, Svend-Erik Skaaning, and Jan Teorell. 2017. V-Dem Comparisons and Contrasts with Other Measurement Projects. V-Dem Working Paper 45.

Economist Intelligence Unit. 2023. Democracy Index 2022: Frontline democracy and the battle for Ukraine.

Elff, Martin, and Sebastian Ziaja. 2018. Method Factors in Democracy Indicators. Politics and Governance 6(1): 105-116.

Freedom House. 2022. Freedom in the World 2022 Methodology.

Marshall, Monty G. and Ted Robert Gurr. 2020. Polity 5: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2018 Dataset Users’ Manual. Center for Systemic Peace.

McMann, Kelly, Daniel Pemstein, Brigitte Seim, Jan Teorell, and Staffan Lindberg. 2021. Assessing Data Quality: An Approach and An Application. Political Analysis.

Møller, Jørgen and Svend-Erik Skaaning. 2021. Varieties of Measurement: A Comparative Assessment of Relatively New Democracy Ratings based on Original Data. V-Dem Working Paper 123.

Skaaning, Svend-Erik. 2018. Different Types of Data and the Validity of Democracy Measures. Politics and Governance 6(1): 105-116.Skaaning, Svend-Erik. 2021. The Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED) Dataset (v6.0) Codebook.

To cover even more of today’s countries when they were still non-sovereign territories we further identified for V-Dem and RoW the historical entity the territories were a part of and used that regime’s data whenever available.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Bastian Herre (2022) - “Democracy data: how sources differ and when to use which one” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/democracies-measurement.html' [Online Resource] (archived on March 4, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-democracies-measurement,

author = {Bastian Herre},

title = {Democracy data: how sources differ and when to use which one},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/democracies-measurement.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.