How many species are there?

How many species do we share our planet with? How many of these species have we found and identified?

How many species do we share our planet with? It's such a basic and fundamental question to understanding the world around us.

It's almost unthinkable that we would not know this number or at least have a good estimate. But the truth is that it's a question that continues to escape the world's taxonomists.

An important distinction is how many species we have identified and described and how many species there actually are. We've only identified a small fraction of the world's species, so these numbers are very different.

How many species have we described?

Before we look at estimates of how many species there are in total, we should first ask the question of how many species we know that we know. Species that we have identified and named.

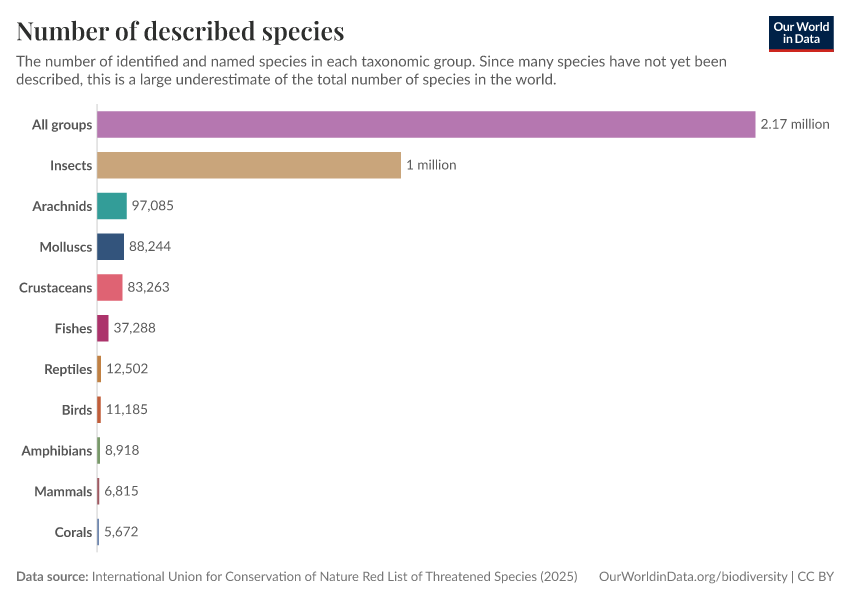

The IUCN Red List tracks the number of described species and updates this figure annually based on the latest work of taxonomists. In 2022, it listed 2.16 million species on the planet. In the chart, we see the breakdown across a range of taxonomic groups — 1.05 million insects, over 11,000 birds, over 11,000 reptiles, and over 6,000 mammals.

These figures — particularly for lesser-known groups such as plants or fungi — might be a bit too high. This is because some described species are “synonyms” — the description of already-known species, simply given a separate name.1 There is a continual evaluation process to remove synonyms (and most are removed eventually), but often species are added at a faster rate than synonyms can be found and removed.2

To give a sense of how large this effect might be, in a study published in Science, Costello et al. (2013) estimated that around 20% of the described species were undiscovered synonyms (in other words, duplicates).1 They estimated that the 1.9 million described species at the time were actually closer to 1.5 million unique species.

If we were to assume this "20% synonym" figure held true, our 2.16 million described species might actually be closer to 1.7 million.

Regardless, we know that all these figures underestimate the actual number of species. The fact that there are so many species that we've yet to discover has real consequences for our ability to understand changes in global biodiversity and the rate of species extinctions.

If we don't know that certain species exist, we also don't know that they might have, or will soon, go extinct. Some species will inevitably go extinct before we realize that they used to exist.

How many species are there really?

As Robert May summarised in a paper published in Science3:

If some alien version of the Starship Enterprise visited Earth, what might be the visitors' first question? I think it would be: “How many distinct life forms—species—does your planet have?” Embarrassingly, our best guess answer would be in the range of 5 to 10 million eukaryotes (never mind the viruses and bacteria), but we could defend numbers exceeding 100 million, or as low as 3 million.

Researchers have come up with wide-ranging estimates for how many species there are. As May points out, this ranges anywhere from 3 to well over 100 million — many orders of magnitude of difference. Some more recent studies estimate that this figure is as much as one trillion.

One of the most widely cited figures comes from Camilo Mora and colleagues; they estimated that there are around 8.7 million species on Earth today.4 Costello et al. (2013) estimate 5 ± 3 million species; Chapman (2009) estimate 11 million; and after reviewing the range in the literature, Scheffers et al. (2012) choose not to give a concrete figure at all.5 More recent studies suggest that the true number is in the billions.

Why is there such a large disagreement on the number of species?

The first challenge is even defining what a “species” is. Even in well-known taxonomic groups — such as birds or reptiles — the delineation of species can change over time.6 Our scientific understanding of organisms, and their relationship to others is still improving. That can mean “splitting” a species into multiple or combining “separate species” into a single one. A clear example of this was when a BirdLife International Review split the Red-bellied Pitta — which was formerly a single bird species — into twelve separate species.

The second challenge is coming up with estimates for groups that are less well-studied than mammals, birds, and reptiles. Most of the disagreement lies in insects, fungi, and other smaller microbial species. Reaching a consensus on such small and inaccessible lifeforms is undoubtedly hard. There are between 6000 to 7000 known mammal species, but 350,000 to 400,000 described species of beetles.7

The biggest area of uncertainty in species estimates is for bacteria and archaea. This can range from mere thousands to billions.8 A 2017 paper by Larsen et al. estimates that there are 1 to 6 billion species on Earth, and bacteria make up 70% to 90% of them.9

The honest answer to the question, “How many species are there?” is that we don’t really know. Estimates span several orders of magnitude, from a few million to billions. Most recent estimates lean towards the higher range. The biggest uncertainty is in the small lifeforms — bacteria and archaea — where we’ve only described a small percentage of the total.

Update

This article was updated in February 2024 with more discussion on the uncertainty of estimates on the number of species globally.

Endnotes

Costello, M. J., May, R. M., & Stork, N. E. (2013). Can we name Earth's species before they go extinct?. Science, 339(6118), 413-416.

Solow, A. R., Mound, L. A., & Gaston, K. J. (1995). Estimating the rate of synonymy. Systematic Biology, 44(1), 93-96.

May, R. M. (2010). Tropical arthropod species, more or less?. Science, 329(5987), 41-42.

Mora, C., Tittensor, D. P., Adl, S., Simpson, A. G., & Worm, B. (2011). How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean?. PLoS Biol, 9(8), e1001127.

Costello, M. J., May, R. M., & Stork, N. E. (2013). Can we name Earth’s species before they go extinct?. Science, 339(6118), 413-416.

A. D. Chapman, Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World (Biodiversity Information Services, Toowoomba, Australia, 2009).

Scheffers, B. R., Joppa, L. N., Pimm, S. L., & Laurance, W. F. (2012). What we know and don’t know about Earth’s missing biodiversity. Trends in ecology & evolution, 27(9), 501-510.

Tobias, J. A., Seddon, N., Spottiswoode, C. N., Pilgrim, J. D., Fishpool, L. D., & Collar, N. J. (2010). Quantitative criteria for species delimitation. Ibis, 152(4), 724-746.

Stork, N. E., McBroom, J., Gely, C., & Hamilton, A. J. (2015). New approaches narrow global species estimates for beetles, insects, and terrestrial arthropods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(24), 7519-7523.

Dykhuizen, D. (2005). Species numbers in bacteria. Proceedings. California Academy of Sciences, 56(6 Suppl 1), 62.

Larsen, B. B., Miller, E. C., Rhodes, M. K., & Wiens, J. J. (2017). Inordinate fondness multiplied and redistributed: the number of species on earth and the new pie of life. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 92(3), 229-265.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2022) - “How many species are there?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/how-many-species-are-there.html' [Online Resource] (archived on March 4, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-how-many-species-are-there,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {How many species are there?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/how-many-species-are-there.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.