The state of the world's elephant populations

How have elephant populations changed over time? What species are at risk of extinction today?

Elephants are the world’s largest living land animals, weighing in at up to 7.5 tonnes.1

Their size has made them a prime target for poaching. History has shown us that it is usually the largest mammals that are most at risk from human hunting. Elephants are no different. We hunt them for their meat, their trunks, and their lucrative tusks.

There are around 450,000 elephants in the world. But many populations are much smaller than they used to be.

In this article we look at the state of elephant populations, and how these populations have changed over time.

State of elephant populations today

There are two species of elephant: the African (with the official name Loxodonta africana) and the Asian (Elephas maximus) elephant.

If you want to tell the difference between them, look at their ears: the African elephant has much bigger ears, very similar in shape to the African continent; the Asian elephant has much smaller, rounded ears.2 Their tusks are also a useful indicator: both male and female African elephants can grow tusks, but only male Asian ones can.

In the table, I have summarized the status of their populations.

Elephant species | Population (latest estimate) | Extinction risk | Population trend |

|---|---|---|---|

African elephant (Loxodonta africana) | 415,000 | By subspecies below | By subspecies below |

African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) | Critically endangered | Decreasing | |

African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana) | Endangered | Decreasing | |

Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) | 40,000 – 50,000 | Endangered | Decreasing |

There are around ten times as many African than Asian elephants in the world. In 2015, there were around 415,000 African elephants left. For the Asian species, this is in the range of 40,000 to 50,000.

The Asian elephant is classified as ‘endangered’, one level down from ‘critically endangered’ before extinction, on the IUCN Red List.3 The African elephant was previously treated as a single species, but has recently been separated into the African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) and African savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana) for evaluation. The forest elephant is listed as ‘critically endangered’ and the savanna elephant as ‘endangered’. The populations of both species are declining.

Are elephant populations increasing or decreasing?

To understand the vulnerability of elephant populations, knowing the the number of animals alive today is not enough. We also need to know the direction and rate of change. If population numbers are falling quickly, we should be concerned even if there are hundreds of thousands left.

Let’s take a look at the African and Asian elephant species one by one.

African elephant (Loxodonta africana)

There are ten times as many African elephants as Asian elephants in the world. That makes them seem abundant. But their numbers are, by several estimates, much smaller than they were in the past.

In the chart below I’ve shown estimates from 1995 onwards from the IUCN’s SSC African Elephant Specialist Group (AfESG). Two lines are shown: in red we have “definitive” estimates that are based on sightings or improved survey counts; and in brown we have these figures plus “probable” counts, which are less certain. As you can see, this affects the total number of estimated elephants but the overall trend in the last few decades is similar.

I’ve also included a single point estimate — of 1.3 million — for 1979. This comes from an earlier paper from Douglas-Hamilton.4 Estimates for 1979 were also modeled by Milner-Gulland and Beddington, as part of a study looking elephant populations over the last few centuries; their models suggested 1979 populations in the range of around 1.1 to 1.8 million.5 This data point not connected to the overall time-series because it’s much less certain, and could be an overestimate.

In a previous version of this chart, I showed a time-series of elephant populations dating back to 1500. This estimated that centuries ago, there were 26 million elephants on the continent. Since then, there has been debate around the quality and credibility of these figures. While in the original chart we made clear that long-run estimates — especially those for from 1900 or earlier — are very crude and come with large uncertainty, the quality of these estimates may be too low to include in our longer time-series.

In the footnote I describe the original sources of some of these estimates.6

While earlier estimates are more uncertain, there have been relatively consistent measurement methods from 2007 onwards. As you can see in the chart above, there was a gradual decline in elephant populations through to 2016. This decline is consistent with trends from the Great Elephant Census, which estimated a reduction of 144,000 from 2007 to 2014.7

Another piece of evidence we have that populations have been in decline comes from a metric called the ‘carcass ratio’.

During population surveys, researchers don’t only count the number of alive elephants, they also count the number of dead elephants (carcasses). The carcass ratio is the number of dead elephants observed during surveys, given as a percentage of the total population.

The carcass ratio across Africa as a whole was 11.9%.8 This means that for every 100 live elephants, there were around 12 dead elephants. A carcass ratio greater than 8% usually means the population is shrinking, because this will be greater than the replacement rate.9 The overall population of African elephants has been falling in recent years. But this varies significantly across countries. In some, the carcass ratio was very high: in Cameroon, it was 83%, it was 32% in Mozambique, and 30% in Angola.10

In the map below you can see the distribution of African elephants across the continent in 2016.

Asian elephant (Elephas maximus)

There are fewer estimates of Asian Elephant populations. This is more worrying because the Asian elephant is at a higher risk of extinction. We should be tracking these numbers more, not less, closely.

We do have some data for select countries, and some longer-term estimates.

The IUCN estimates that the total population of Asian elephants has more than halved over the past century. It estimates that there were 100,000 animals in the early 1900s; today that figure is in the range of 40,000 to 50,000.

Population data over time is available for some countries in Asia: the Indian government, for example, has published estimates periodically since 1970.

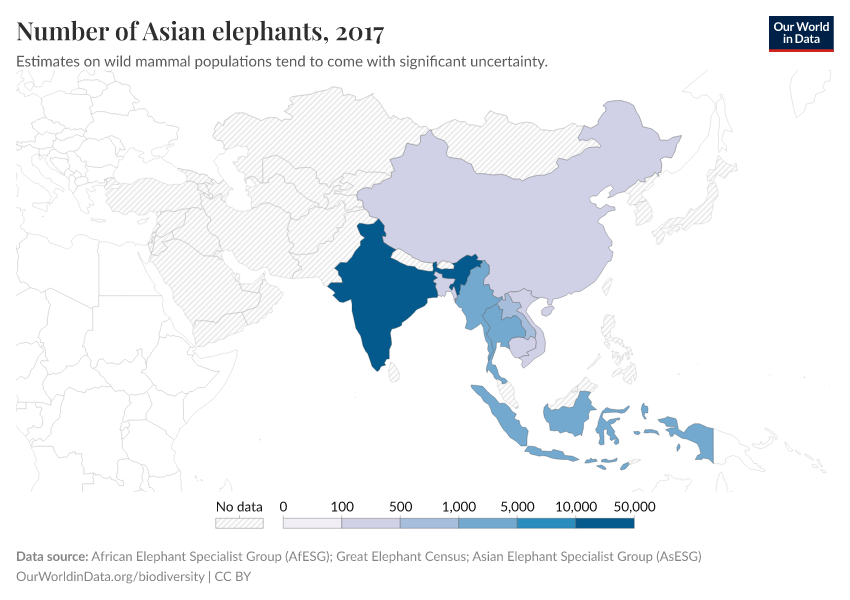

In the map, you can explore the latest population estimates from the Asian IUCN SSC Asian Elephant Specialist Group (AsESG) for each country.

In India, populations have been steadily increasing since 1980, rising from around 16,000 to over 27,000 in 2017. This shows that it’s possible to protect these species and help their populations rebuild.

However, the lack of data over time for many countries makes it difficult to properly assess the health of Asian elephant populations.

How to save our elephant populations

By far the biggest threat to both African and Asian elephants is poaching. Elephants are killed for their trunks and their tusks. Ivory is a lucrative business.

It’s not just elephants that are under pressure.

Poaching is the leading threat to all large mammals. But as we’ve seen from some country-level examples: protecting these species is possible: India has managed to protect and restore elephant populations. Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Angola have also managed to turn the trend.

Updated

This article and its charts were first published in 2019. It was updated in 2024, when longer-run estimates of African elephant populations were excluded due to concerns about data quality. You can find more context on this within the article. Thanks to Tin Fischer for flagging this issue.

Endnotes

African elephants are typically bigger than the Asian species. African elephants can weigh up to 7.5 tonnes; Asian elephants up to 5 tonnes.

Elephants dissipate heat via their ears, and so use them for temperature regulation. The reason that African elephants have larger ears is that they live in warmer climates and therefore need to dissipate more heat.

Choudhury, A., Lahiri Choudhury, D.K., Desai, A., Duckworth, J.W., Easa, P.S., Johnsingh, A.J.T., Fernando, P., Hedges, S., Gunawardena, M., Kurt, F., Karanth, U., Lister, A., Menon, V., Riddle, H., Rübel, A. & Wikramanayake, E. (IUCN SSC Asian Elephant Specialist Group) 2008. Elephas maximus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008.

Douglas-Hamilton (1979). Elephant Survey and Conservation Programme: final and annual report 1979. IUCN/WWF.

Milner-Gulland, E. J., & Beddington, J. R. (1993). The exploitation of elephants for the ivory trade: an historical perspective. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences.

The original estimates for 1500 and 1913 came from the Great Elephant Census project. These estimates were published on its main project page here (which has subsequently been taken down, but can be accessed via web archive).

The Great Elephant Census (GEC) was one of the largest wildlife surveys to date, and attempted to provide continent-wide estimates of elephant populations and trends using aerial surveys. Its results were published in a peer-reviewed journal in 2016.

There, the authors note that “Africa may have held over 20 million elephants before European colonization and 1 million as recently as the 1970s.” The papers they reference there do provide estimates of this order of magnitude for the 1800s and 1970s, but do not provide estimates for 1500. I can only assume that there was an error in translating this on to the project’s main page, hence why it assumed a 1500 estimate of 26 million. This is likely to have been an estimate for 1813.

The underlying paper by Milner-Gulland and Beddington (1993) does estimate that elephant populations were around 13.5 to 27 million in 1813. It estimates that the “pristine carrying capacity” was around 27 million, and that the population was 50% to 100% of this carrying capacity.

As I mentioned, these estimates — as the authors acknowledge — are crude and come with large uncertainty. Other researchers in this area find them to be unlikely. While they could still be solid estimates, I think the lack of confirmatory studies since then makes their quality too low to include in our longer time-series.

Chase, M. J., Schlossberg, S., Griffin, C. R., Bouché, P. J., Djene, S. W., Elkan, P. W., ... & Sutcliffe, R. (2016). Continent-wide survey reveals massive decline in African savannah elephants. PeerJ.

Milner-Gulland, E. J., & Beddington, J. R. (1993). The exploitation of elephants for the ivory trade: an historical perspective. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences.

Douglas-Hamilton, I. 1988 African elephant population study - phase 2. Nairobi: WWF/UNEP.

Chase, M. J., Schlossberg, S., Griffin, C. R., Bouché, P. J., Djene, S. W., Elkan, P. W., ... & Sutcliffe, R. (2016). Continent-wide survey reveals massive decline in African savannah elephants. PeerJ.

Chase, M. J., Schlossberg, S., Griffin, C. R., Bouché, P. J., Djene, S. W., Elkan, P. W., ... & Omondi, P. (2016). Continent-wide survey reveals massive decline in African savannah elephants. PeerJ, 4, e2354.

Douglas-Hamilton, I., & Burrill, A. (1991). Using elephant carcass ratios to determine population trends. African wildlife: research and management, 98-105.

Data is only available for the years 2007 and 2015. So even countries which show an increase in over this decade – Cameroon, for example – might have seen a decline in very recent years, which is reflected in carcass ratio data.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2024) - “The state of the world's elephant populations” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251125-173858/elephant-populations.html' [Online Resource] (archived on November 25, 2025).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-elephant-populations,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {The state of the world's elephant populations},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2024},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251125-173858/elephant-populations.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.