People around the world have gained democratic rights, but some have many more rights than others

How democratic have countries been across the world? And how big are the differences between them?

200 years ago, everyone lacked democratic rights. Now, billions of people have them.

But there are still large differences in the degree to which citizens enjoy political rights: most clearly between democracies and non-democracies, but also within these broad political regimes.

To understand the extent of people’s political rights, we shouldn’t only look at whether a country is classified as a democracy or not. We should also look at smaller differences in how democratic countries are.

How democratic have countries been across the world? And how big are the differences between them?

To answer these questions, we need information on countries’ political systems over recent centuries.

How can researchers measure how democratic a country is?

Measuring how democratic countries are comes with many challenges. People do not always agree on what characteristics define a democracy. Its characteristics — such as whether an election was free and fair — are difficult to assess. The assessments of experts are to some degree subjective and they may disagree; either about a specific characteristic, or how several characteristics can be reduced into a single measure of democracy.

Because of these difficulties, classifying political systems is unavoidably controversial. I have written more about how researchers deal with the challenges of measuring democracy in another article.

The source we show here is the electoral democracy index from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project1. In our Democracy Data Explorer, however, we show the data for several leading approaches, so that you can compare how different sources score democracy across the world.

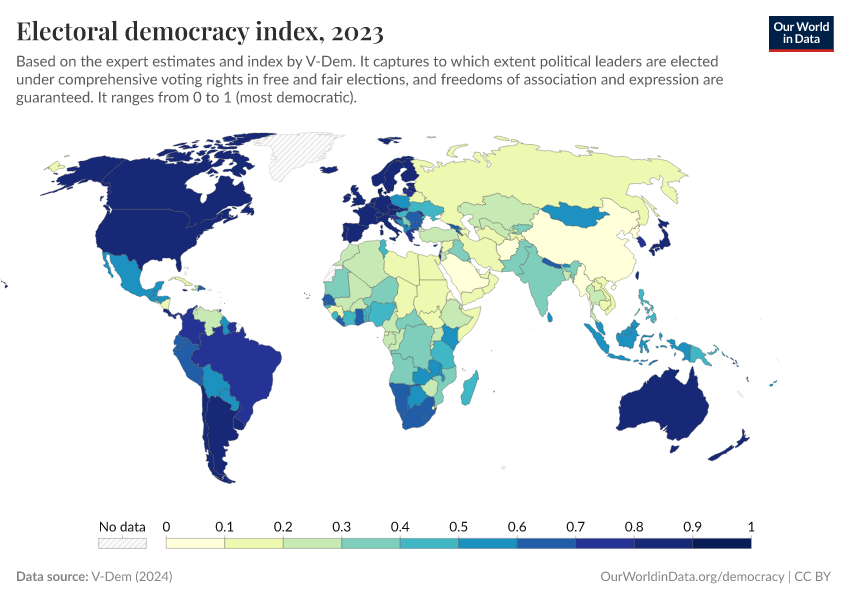

The electoral democracy index from V-Dem tries to capture the extent to which political leaders are elected under comprehensive voting rights in free and fair elections, and freedoms of association and expression are guaranteed.2

The interactive map shows how democratic each country is at the end of each year, going back in time as far as 1789. To explore changes over time, you can drag the time-slider below the map.

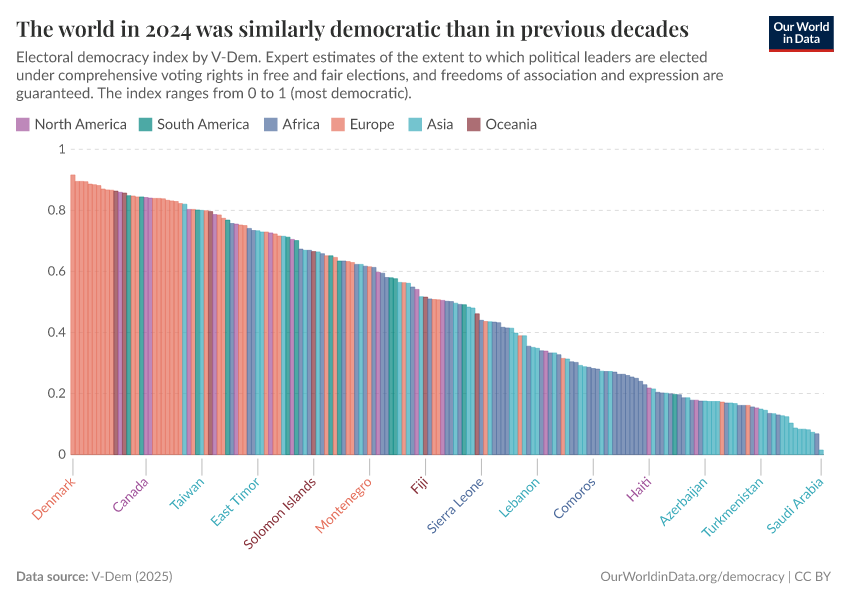

We see that countries differ in how democratic they are, with some countries close to the index’s maximum of 1, and others close to its minimum score of 0. Most countries are somewhere in the middle.

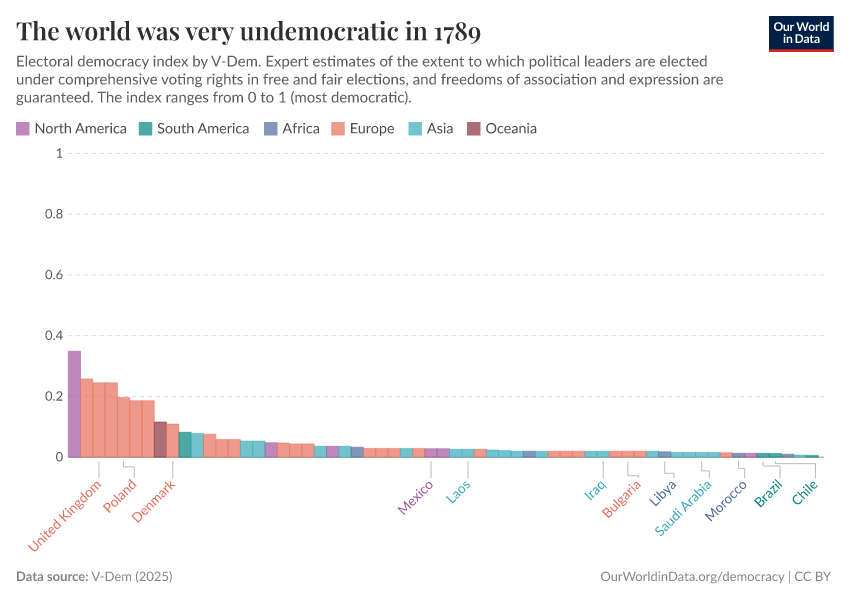

The world was highly undemocratic in the 18th and 19th centuries

The world did not always look like it does today. It has become much more democratic over time.

A very clear way of showing this is to look at the distribution of democracy scores at different stages in history.

Here we do this in the form of a bar chart, where electoral democracy is again measured on a scale from 0 to 1. The shortest bars here are the least democratic countries, the highest bars indicate the most democratic.

This means that the area covered by all of the bars gives us a proxy for the extent of democracy globally.

In the data’s earliest available year, 1789, the world was very undemocratic: most of the world’s political leaders were unelected, few people had voting rights, elections were neither free nor fair, and citizens were not able to assemble and speak freely.

Only a few countries, such as France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, had a few democratic characteristics. The United States was the most democratic country according to V-Dem’s assessment, but still only received a score of 0.35.

In this sense, the world was more equal than it is today: democratic rights were very limited everywhere.

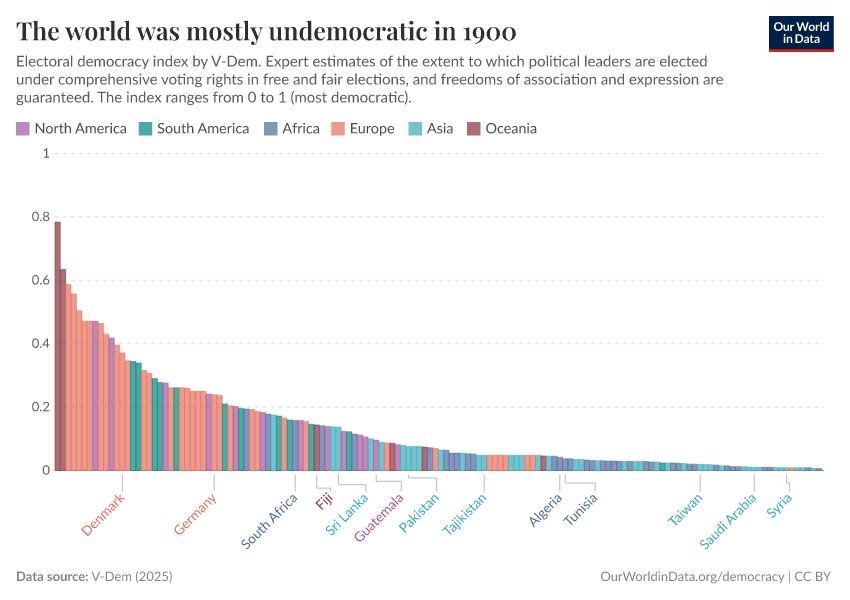

The world was mostly undemocratic in the early 20th century

By 1900, political institutions had become more diverse, but remained highly undemocratic in most countries.

A fair number of countries in Europe and the Americas now had some democratic features: in particular, citizens had become freer to associate and express their opinions. A couple of countries, such as Australia, France, and Switzerland, had even developed fairly democratic features, with men now having the right to vote and almost all political leaders being chosen in elections.

The most democratic country, with a score of 0.78, was New Zealand.

But the many other countries, most under colonial rule, had political systems that granted few democratic rights to their citizens: the colonial powers installed unelected leaders, gave no or only few citizens the right to vote, and restricted citizens’ ability to assemble and express their opinions.

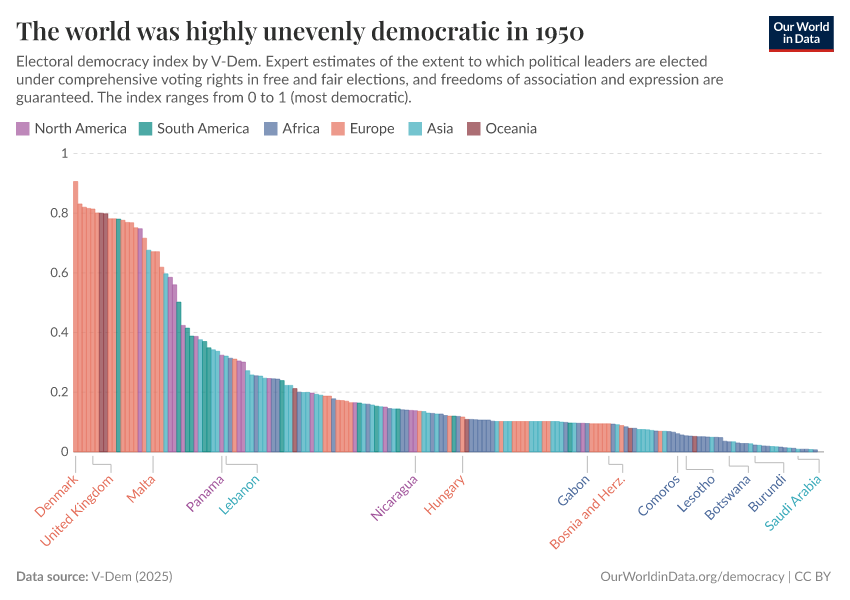

Democratic rights became highly unequal across the world in the first half of the 20th century

In the first half of the 20th century, some countries continued to become more democratic, while progress in most others stalled.

More democratic political institutions in Europe after the First World War were almost completely undone in the two decades that followed, but were then reestablished after the second World War. Some non-European countries such as Canada and the United States also extended the democratic rights of their citizens.

In the rest of the world, however, countries broadened some political rights while remaining overwhelmingly undemocratic. The colonial powers at times expanded voting rights and loosened restrictions on freedoms of expression and association, but local political leaders remained unelected, or the elections choosing them were marred by violence, intimidation, or fraud.

This meant that democratic rights were distributed highly unequally across the world’s inhabitants, shown by the chart’s steep slope.

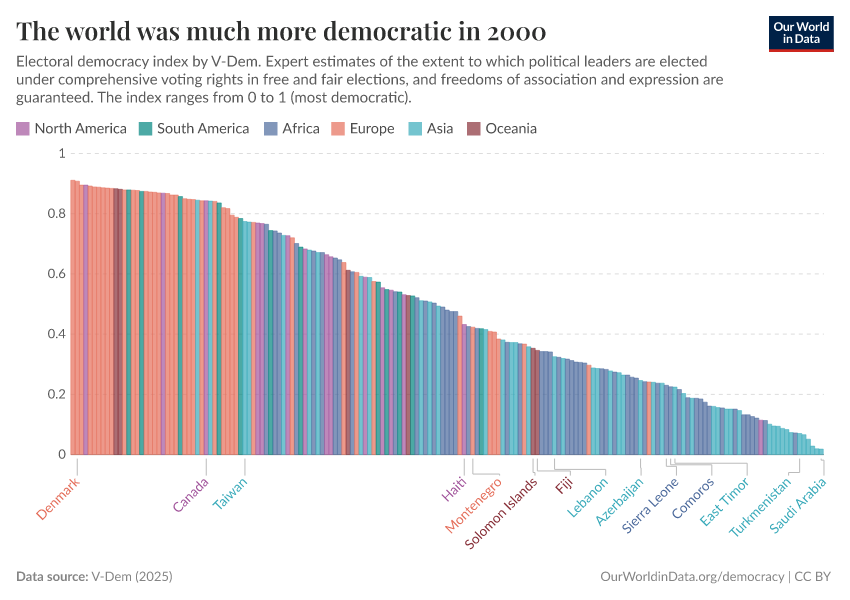

Democracy spread across the world in the second half of the 20th century

Many countries then became much more democratic in the second half of the 20th century.

In the 1990s especially, democratic institutions expanded across the world. Countries in South America shed their highly autocratic political systems that had spread in the 1970s. According to V-Dem, a considerable number of countries in Africa became fairly democratic (such as Ghana and South Africa) in the decades after gaining independence. Civil society organizations and political parties could operate more freely, and elections became freer and fairer.

And while many countries in Asia and the Middle East remained decidedly undemocratic, some countries in these regions expanded democratic rights, such as India, Indonesia, Turkey, and South Korea.

Democratic rights therefore became much more evenly distributed across the world.

Democracy’s spread has slowed in the 21st century

The spread of democracy has slowed in the 21st century compared to previous decades.

While some countries became more democratic according to V-Dem, such as Tunisia and Peru, many stagnated or became less democratic — some, such as India, Indonesia, Mexico, and Poland considerably so.

Despite these declines in democracy, almost all countries remain much more democratic than they were at the beginning of the 20th century.

And they remain vastly more democratic than most countries during the 18th and 19th centuries: a score of 0.11 made Denmark one of the most democratic countries in 1789, while the same score made Nicaragua an average country in 1900, and the United Arab Emirates one of the least democratic countries in the world in 2023.

Some countries are much more democratic than others

While the world has become much more democratic over the last 200 years, there are still large differences between countries.

As the previous chart shows, some countries — mostly located in Europe and the Americas — are highly democratic: they have elected political leaders, elections are free and fair, and most citizens have the right to vote and can associate and express their opinions freely. The most democratic countries were Denmark and Ireland, with scores of 0.92 and 0.90.

Other countries, concentrated in Asia, are highly undemocratic according to V-Dem. This includes countries such as China, North Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and the least democratic country in the world, Saudi Arabia, with a score of just 0.01. In these countries, citizens do not have the right to choose their political leaders in popular elections.

Most countries, often situated in Africa and East and Southeast Asia, fall somewhere in the middle. In these countries, political leaders usually are elected and most citizens have the right to vote, but their rights to associate and express their opinions are limited, and elections are not entirely free and fair.

As mentioned, V-Dem is only one of the leading approaches to measure democracy. And its electoral democracy index is only one main measure it provides alongside other, more comprehensive indices of democracy.

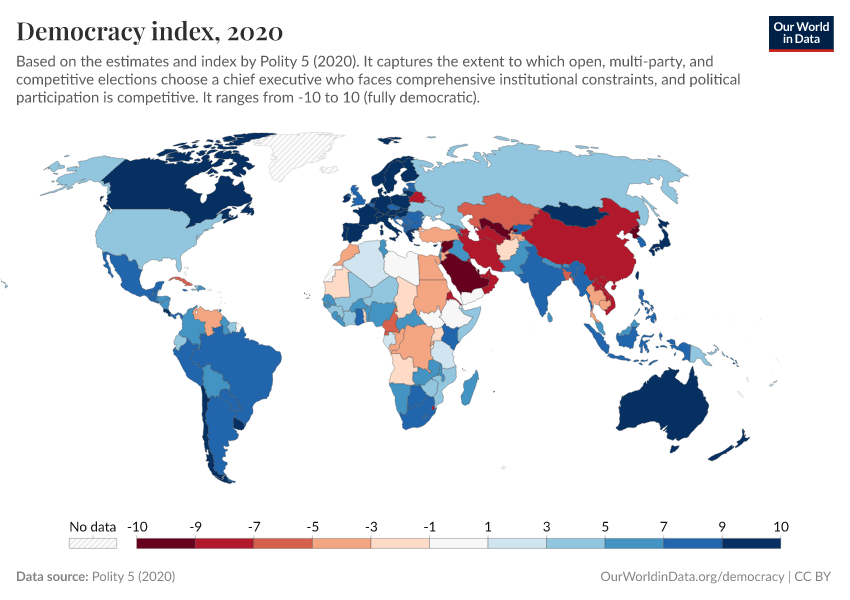

Yet, using another approach or V-Dem index to measure democracy shows a similar development from a highly undemocratic world in the 18th and 19th century, to high democratic inequality in the earlier 20th century, and a much more democratic, and more equally democratic, world in recent decades.

You can see so for yourself by exploring the four charts below, which use the Polity project’s democracy index and V-Dem’s liberal democracy index.

Taken together, the democratic political systems of many countries show that a world where people have much more say in how they are governed is possible.

But the fact that so many countries are still highly undemocratic means that the fight for democratic political rights goes on.

Keep reading at Our World in Data

Acknowledgements

I thank Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser for their very helpful comments and ideas about how to improve this article.

Endnotes

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Fabio Angiolillo, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Linnea Fox, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Ana Good God, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Joshua Krusell, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Natalia Natsika, Anja Neundorf, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Marcus Tannenberg, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Felix Wiebrecht, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2025. "V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v15" Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

While we use V-Dem’s data, we expand the years and countries covered. You can find more information in this article.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Bastian Herre (2022) - “People around the world have gained democratic rights, but some have many more rights than others” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/democratic-world.html' [Online Resource] (archived on March 4, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-democratic-world,

author = {Bastian Herre},

title = {People around the world have gained democratic rights, but some have many more rights than others},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2022},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260304-094028/democratic-world.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.