Emerging COVID-19 success story: Germany's strong enabling environment

Germany is one country which has responded well to the Coronavirus pandemic. How did they do so? In-country experts provide key insights.

This is a guest post from Lothar Wieler (Robert Koch Institute), Ute Rexroth (Robert Koch Institute), and René Gottschalk (Health Protection Authority, City of Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main) as part of the Exemplars in Global Health platform.

Notice

This article was published earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, based on the latest published data at that time.

We now source data on confirmed cases and deaths from the WHO. You can find the most up-to-date data for all countries in our Coronavirus Data Explorer .

Read the updated version of this article published 20 March 2021.

An updated version of this article covers the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany from January 2020 through January 2021.

Introduction

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Germany has shown several elements of success across the four phases of our preparedness and response framework: prevent, detect, contain, and treat. The country’s incredibly strong enabling environment, including a good local public and health care system and expert scientific institutions, has largely contributed to this broad-based progress.

Germany did not prevent the COVID-19 outbreak, but the prevention protocols in place facilitated the country’s response to the outbreak. These protocols included early establishment of testing capacities, high levels of testing (in the European Union, Germany is a leader in tests per confirmed case), an effective containment strategy among older people (which may explain why Germany has a much lower case fatality rate than comparable countries), and efficient use of the country’s ample hospital capacity.

Prevent: Local health authorities, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) – Germany’s public health institute – and other scientific institutions have produced data and analysis to inform Germany’s response. RKI and scientists at other institutions mobilized in early January to launch national crisis management to understand the epidemiology of the pandemic.

Detect: One of the first diagnostic tests for COVID-19 was developed at Berlin’s Charité hospital, and the government worked to mobilize the country’s public and private laboratories to rapidly scale up testing capacity. Later, Germany became a pioneer in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, which continues to feature prominently in the national strategy.

Contain: Germany’s greatest success in this area has been relatively limited transmission in long-term care facilities. Because older people are more likely than younger people to die from the virus, the country is at higher risk because of its older population. The comparable low rate of infection among Germany’s population over age 70 is probably one driver of its relatively low case fatality rate overall.

Treat: With a large number of hospital beds and careful planning, Germany’s intensive care units (ICUs) have not been overly stressed, although health care workers have had to contend with shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE).

In April, Germany began relaxing its physical distancing measures, a strategy driven by data and science. This approach is informed by continuous tracking of key indicators and will be supplemented by findings from serological testing. A month after Germany began to relax physical distancing, the disease has shown few signs of resurging.

Context

Country overview

Germany has the fourth largest economy in the world and spends approximately 11 percent of its gross domestic product on health care, with US$5,119 spent per capita per year.1,2 As a result, the capacity of Germany’s health care system is considered to be very high. In the European Union (EU), Germany has the most hospital beds per 1,000 people (8.3)3 and a robust sector of private and public laboratories, of which nearly 200 indicate capacity for SARS-CoV-2-tesing.4 It also ranks among the top five countries in the European Union for the number of nurses (13.2) and physicians (4.2) per 1,000 people.5

Germany has traditionally held the most restriction-free and consumer-oriented health care system in Europe.6 Health insurance is mandatory for all citizens and permanent residents of Germany, with approximately 90 percent of the population covered through nonprofit nongovernmental insurance funds and around 10 percent of the population covered through private insurance. In a Commonwealth Fund survey, Germany has the lowest wait times for both consultations with specialists and elective surgeries.7

The user-friendliness of the health care system and its ample human resources and physical infrastructure have led to exceptional and continuously improving health indicators. For example, life expectancy at birth grew from 75 years in 1990 to 81 years in 2018,8 and the maternal mortality ratio also decreased from 11 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to 7 in 2017.9

Outbreak timeline

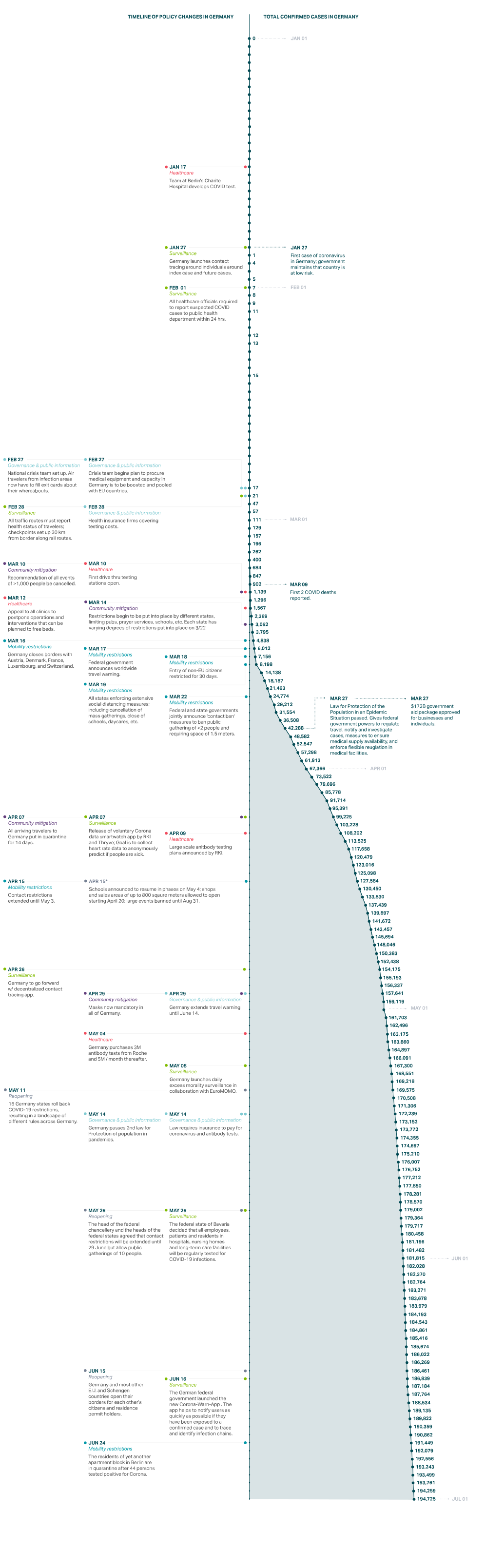

The first case in Germany was reported on January 27in Bavaria. On February 1, the government further clarified reporting obligations and mandated that all health care providers report suspected cases of COVID-19 within 24 hours to local public health authorities.10 On February 27, with a total of 26 confirmed cases, the government set up an inter-ministerial national crisis management group. The next day, the government required all travelers entering the country from high-risk areas (such as, at that time, areas in China or Italy) to provide information about possible previous exposure and contact details.11 Testing is available at no cost to the patient upon medical or epidemiological indication and testing for epidemiological indications was also recently included in asymptomatic contacts or screenings. RKI began issuing daily situation reports for the national and international public health sector on January 23, although the first reports were confidential due to the granularity of the data.

Risk assessments and technical guidelines for testing, case finding, contact tracing, hygiene, and disease management, as well as various other documents, have been available since January 16. At the end of February and beginning of March, mass gatherings and travel were increasingly restricted. On March 10, mass gatherings with more than 1,000 participants were prohibited. In mid-March the federal states started to close schools. On March 18, non-EU citizens were barred from entering the European Union for 30 days.12 On March 22, Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that the federal states and national government had jointly decided to implement a “contact ban,” limiting public gatherings to two people (outside families), requiring physical distance of at least approximately 5 feet (1.5 meters), and closing many businesses. The contact ban was not a lockdown: The population remained free to leave the house, such as for walks. On April 10, all travelers arriving in Germany, regardless of their origin, were required to quarantine for 14 days.

All of these measures paid off. By April 15, when new cases reported per day numbered approximately 2,000 (compared to a peak in March of 6,000), the government announced a gradual easing of physical distancing measures. Thus far, the relaxation of these physical distancing measures has not caused an increase in new infections. On May 22, there were 460 new infections, indicating that Germany’s contact tracing and robust testing and treatment strategies may have brought the country through the most severe portion of the outbreak.

Germany Country Profile

Explore Coronavirus data for Germany in its own country profile

Prevent

Epidemiological expertise and surveillance

The German government entered the pandemic with a detailed National Pandemic Plan.13 Together with generic preparedness plans and other disease-specific plans and documents (e.g., for MERS), this detailed response plan enabled the government to activate quickly, with no time wasted on disputes related to governance, accounting, or costs.14

Because Germany is a highly federalized country, the responsibility for public health lies primarily with intermediate and local public health authorities in 16 federal states and approximately 400 counties. They adapt the national guidelines and recommendations to local needs. National authorities facilitate nationwide exchange and negotiate standards and common procedures.

As Germany’s national public health institute, RKI is dedicated to the prevention, control, and investigation of infectious diseases. In addition to routine surveillance, its team of scientists conducts research on infectious disease pathogenesis, risk assessment, epidemiology, and sentinel surveillance systems to support the federal government, local and intermediate public health authorities, and health professionals during outbreaks.15 RKI publishes risk assessments, strategy documents, response plans, daily surveillance reports on COVID-19, and technical guidelines, and works with national and international public health authorities as channels for distributing communication. This steady flow of information has helped the government—as well as local and intermediate public health authorities, health professionals, and the population—make critical decisions during the outbreak.

Detect

Testing

In January 2020, scientists at Germany’s Charité hospital developed one of the first specific tests for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in patients, which is now used widely around the world.16 The World Health Organization adopted it as one of the core diagnostic tests. Given how quickly the test was developed, Germany was able to turn its attention early to growing its testing capacity.17 The country was uniquely positioned to do this because its laboratories have the expertise, accreditation, and equipment to conduct PCR assays and quickly deliver diagnoses. On February 28, the government facilitated this process by mandating that all insurance companies pay for COVID-19 tests,18 incentivizing private laboratories to scale up quickly. On May 14, Germany extended this law to include testing of asymptomatic people to expand testing of at-risk groups who may have come in contact with COVID-19 patients, especially health care workers and those in nursing homes.19 As of May 11, 2020, Germany has conducted 18.6 tests per positive case, more than Italy (11.9), Spain (8.4), United States (7), United Kingdom (6.4), and France (6.3), but less than South Korea (68.1).20

Contact tracing

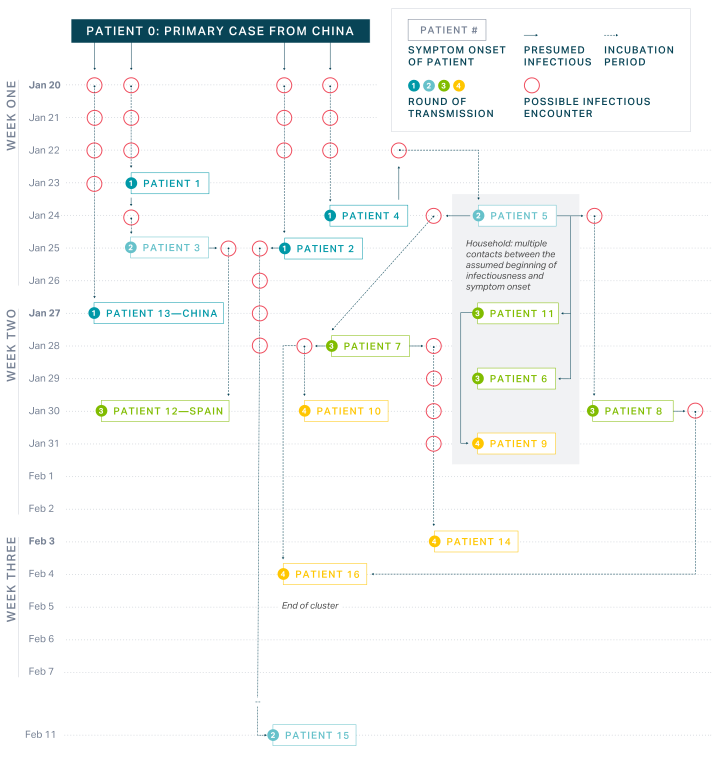

Bavarian health authorities and scientists closely examined—and eventually broke—the chain of transmission among the first cluster of cases, which occurred at the end of January in Bavaria. Breaking this initial chain bought Germany critical time to design its response while yielding important lessons about how the disease is transmitted.21 By using a combination of epidemiological methods such as interviews and whole genome sequencing, the team was able to reconstruct and describe transmission events precisely. This research provided details on attack rates, incubation periods, and the serial interval, which provided critical information that enabled public health experts to estimate the potential size of the epidemic and decide on appropriate containment measures.22

Even when the number of cases grew exponentially in Germany, local public health and intermediate and national authorities continued to make tremendous efforts to conduct contact tracing for every single case, despite a lack of staff. Citizen science projects were launched to complement the government’s efforts: RKI released the Corona-Datenspende (Corona Data Donation) smartwatch app on April 7. The app works by collecting activity and heart rate data, along with postal codes, and analyzing the information for potential COVID-19 symptoms.23 The app is voluntary, and the collected information is currently being analyzed. In addition, RKI analyzes the aggregated and anonymized data of mobile phones to identify changes in the mobility of citizens.

The government also planned to develop a centralized contact tracing app that would enable health authorities to alert others who may have come into contact with people who were confirmed positive. After pushback due to privacy concerns, Germany decided to adopt a decentralized, anonymous approach to contact warning. It will work by asking individuals to report their positive test status via the app, and Bluetooth connections between phones trigger alerts to people who had come into contact with someone who tested positive.25 This app is also voluntary, so its effectiveness will depend on how many people download it and whether infected patients report their positive test status.

The biggest need related to contact tracing is human resources at local public health facilities, many of which are understaffed. The German Federal Ministry of Health and RKI hired and trained “containment scouts”— typically medical students—to support local authorities in tracing contacts.26 Health leaders emphasize the fundamental importance of contact tracing and need to maintain staff levels to keep caseloads low, so that contract tracers can keep up with the volume. Following up with all contacts becomes more difficult during larger outbreaks, regardless of the level of contact.

Antibody testing

German scientists from the University of Bonn conducted some of the world’s first COVID-19 antibody studies in the hard-hit town of Gangelt, where it found community infection rates of nearly 14 percent.27 Among other scientific institutions planning serological studies, as part of its long-term strategy, RKI has announced a three-pronged approach to gathering data about community spread, with the idea that the data will help shape more sensitive policies in the future. The elements of its approach are:

- Serological examination of blood donors: Starting in April 2020, 5,000 blood samples from adults will be examined every 14 days to learn what percentage have antibodies present.

- Serological examination of COVID-19 hot spots in Germany: A representative sample of approximately 2,000 volunteers who are over 18 years and living in harder-hit areas within Germany will be examined several times. These volunteers will also be asked questions about clinical symptoms, previous illness, health behavior, living conditions, and mental health. This study started in mid-April 2020.

- Nationwide population representative screening: 15,000 people over the age of 18 are being examined at 150 study locations around the country. These people are meant to be a representative sample of the country.28

Contain

The first major international satellite outbreak outside of China happened in Germany at the end of January. A single index case from China hit Bavaria, a well-equipped region, but the local and regional resources for contact tracing were still immediately stretched.29 On February 1, 2020, the first flight of mainly German citizens returning from Wuhan arrived at Frankfurt Int'l Airport. PCR tests were carried out on all passengers to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2, and two passengers were discovered to be positive. It was possible to prevent secondary cases, but cytopathic effects showed that both asymptomatic patients could have been contagious.30

These experiences may have increased awareness among health professionals and the public, so when several larger outbreaks began spreading a month later, information and technical guidelines were available and the public and politicians were alert.

On March 22, Germany enforced strict physical distancing guidelines, banning groups of more than two people in public and shutting down some businesses. Unlike many other EU countries, however, Germany never issued a curfew.

The average age of German citizens is 46, putting them at higher risk of complications from COVID-19 than younger populations; the average age of COVID-19 patients is 49.31,32 Germany’s case fatality rate among patients over 70 is the same as in most European Union countries (20.5 percent, compared with 18.9 percent in Spain and 19.5 percent in Italy).33,34 However, Germany has been able to limit the number of infections of people older than 70.Of Germany’s total number of cases, 19 percent are older than 70, compared with 36 percent in Spain and 39 percent in Italy. As a result, overall case fatality rates in Germany as of May 2020 are 4.6 percent, compared with 14.1 percent and 12 percent in Italy and Spain, respectively.35 South Korea has fared similarly to Germany by managing to keep infections among the over-70 population to only 11 percent of all cases, reporting a case fatality rate of 17 percent for this group, and maintaining a low overall case fatality rate of 2.4 percent.36 These data seem to indicate that quality of care for older patients does not vary widely among countries, but the success of containment among high-risk populations does.

In Germany the first outbreaks affected travelers, festivals, and workplaces, not nursing homes, which may have helped limit infections among older people. Eventually, there were more outbreaks among older people, but the majority of cases occurred in other settings.37 Germany has also been able to manage infection rates in hospitals and long-term care facilities. According to RKI national guidelines, recovered COVID-19 cases who return into care homes from hospitals must have tested negative or have undergone quarantine at an isolation area for 14 days.38 Furthermore, specific guidance is provided to nursing homes on hygiene measures and protocols to handle suspected and confirmed cases as well as outbreaks.39 Older people were also tested more often than younger age groups.

As of May, 37 percent of all deaths in Germany occurred in people who were cared for or accommodated in facilities such as facilities for the care of older, disabled, or other persons in need of care, homeless shelters, community facilities for asylum-seekers, repatriates and refugees as well as other mass accommodation and prisons. However, the percentage is much higher in several neighboring countries: 51 percent in Belgium, 66 percent in France, 61 percent in Norway, 66 percent in Spain, and 50 percent in Sweden.40

Treat

In March a register of ICUs was established by the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine and RKI.41 Since April 16, ICU capacity and COVID-19 patients treated in ICU have been reported daily. These data help to understand the severity of the disease and potential impacts on the health care system. Based on daily reports showing a long-term trend of sufficient ICU capacity, the government passed a law on May 14 providing free ICU care to patients from other EU countries.42

The management of supplies of PPE has not been as successful. The government launched a crisis team to centrally procure PPE,43 and on March 4 it banned the export of all PPE.43 Despite these measures, Germany has seen shortages of more than 100 million single-use masks, 50 million filter masks, and 60 million aprons and disposable gloves, leading to a protest by health care providers on April 27.44 German authorities continue to work on procuring these supplies, but like many other countries around the world, they have yet to entirely solve the problem.

Conclusion

Germany’s strong health care system and early progress on detection complemented its effective containment strategy. Ensuring the increase of human resources among understaffed local public health facilities was another key component to enable more efficient contact tracing, but these resources may not be sustainable. Overall, Germany’s focus on collecting and analyzing data and communicating the results to the public is leading to an informed set of policy choices that is generating unusual levels of public support. Germany’s federal system has led to varied approaches and guidance from each state in distancing measures and subsequent loosening measures as well as greater capacity in the health system as a product of redundancies.

As of May, Germany is moving forward with relaxing its physical distancing guidelines but is doing so based on a data-driven rationale. Chancellor Angela Merkel regularly cites RKI surveillance data and uses epidemiological concepts such as reproduction rate as a driving factor behind decisions related to social distancing measures.45 The German government is focusing on three indicators—infection rate, disease severity, and health system capacity—to measure the quality of its response. Setting clear expectations and providing transparency to the public on the criteria for government decision making about reopening is a key factor in gaining public trust.

Immediately after relaxing measures, Germany saw a slight uptick in the virus reproduction rate46 but has been able to identify outbreaks in nursing homes and slaughterhouses to stop transmission. Germany has been successful in limiting the extent of its outbreak early on, but the key question over the coming months is whether it can prevent a second wave of infections while allowing greater freedom of movement.

In-depth explainers on Exemplar countries

This framework identified three countries which provide key success stories in addressing the pandemic: South Korea, Vietnam and Germany. In follow-up articles, in-country experts provide key insights into how these countries achieved this.

How experts use data to identify emerging COVID-19 success stories

How can we define success stories in addressing COVID-19?

South Korea

Emerging COVID-19 success story: South Korea learned the lessons of MERS

Vietnam

Emerging COVID-19 success story: Vietnam's commitment to containment

This article is one of a series focused on identifying and understanding Exemplars in the response to the Coronavirus pandemic. It is hosted by the Exemplars in Global Health (EGH) platform.

Exemplars in Global Health is a coalition of experts, funders, and collaborators around the globe, supported by Gates Ventures and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, who share the belief that rigorously understanding global health successes can help drive better resource allocation, policy, and implementation decisions. The Exemplars in Global Health platform was created to help decision-makers around the world quickly learn how countries have solved major health and human capital challenges.

Endnotes

World Bank. GDP (current US$) – Germany [data set]. World Bank Data. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=DE&view=chart. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, Wharton GA. International Health Care System Profiles – Germany. The Commonwealth Fund. June 5, 2020. https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/germany/. Accessed June 6, 2020.

World Bank. Hospital beds (per 1,000 people) – Germany [data set]. World Bank Data. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=DE&most_recent_value_desc=true. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Germany excels among its European peers. The Economist. April 25, 2020. https://www.economist.com/europe/2020/04/25/germany-excels-among-its-european-peers. Accessed June 1, 2020.

World Bank. Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Germany [data set]. World Bank Data. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?locations=DE&most_recent_value_desc=true. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Björnberg A. Euro Health Consumer Index 2018. Marseillan, France: Health Consumer Powerhouse; 2018. https://healthpowerhouse.com/media/EHCI-2018/EHCI-2018-report.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2020.

The Commonwealth Fund. 2010 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2010/nov/2010-commonwealth-fund-international-health-policy-survey. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2010.

World Bank. Life expectancy at birth, total (years) – Germany [data set]. World Bank Data. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=DE&name_desc=true. Accessed June 2, 2020.

United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Maternal Mortality in 2000-2017: Internationally Comparable MMR Estimates—Germany. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. https://www.who.int/gho/maternal_health/countries/deu.pdf?ua=1. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Empfehlungen des Robert Koch-Instituts zur Meldung von Verdachtsfällen von COVID-19 [Recommendations from the Robert Koch Institute for reporting suspected cases of COVID-19]. Robert Koch Institute website. Last updated May 29, 2020. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Empfehlung_Meldung.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronik der bisherigen Maßnahmen [Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronology of measures taken]. German Federal Ministry of Health. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/en/coronavirus/chronologie-coronavirus.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Daily Situation Report of the Robert Koch Institute. April 3, 2020. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/2020-03-04-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Robert Koch Institut. Ergänzung zum Nationalen Pandemieplan – COVID-19 – neuartige Coronaviruserkrankung [Supplement to the National Pandemic Plan - COVID-19 - Novel Coronavirus Disease]. Berlin: Robert Koch Institute; 2020. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Ergaenzung_Pandemieplan_Covid.html. Accessed June 8, 2020.

Eckner C. How Germany has managed to perform so many Covid-19 tests. The Spectator. April 6, 2020. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/how-germany-has-managed-to-perform-so-many-covid-19-tests. Accessed June 1, 2020.

What we do – Departments and units at the Robert Koch Institute. Robert Koch Institute website. https://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Institute/DepartmentsUnits/DepartmentsUnits_node.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Researchers develop first diagnostic test for novel coronavirus in China. [Press release]. Charite. January 16, 2020. https://www.charite.de/en/service/press_reports/artikel/detail/researchers_develop_first_diagnostic_test_for_novel_coronavirus_in_china/. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Eckner C. How Germany has managed to perform so many Covid-19 tests. The Spectator. April 6, 2020. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/how-germany-has-managed-to-perform-so-many-covid-19-tests. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Information on testing. Zusammen gegen Corona website. https://www.zusammengegencorona.de/en/inform/information-on-testing/. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Zweites Gesetz zum Schutz der Bevölkerung bei einer epidemischen Lage von nationaler Tragweite [Second law to protect the population in an epidemic situation of national scope]. German Federal Ministry of Health. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/en/covid-19-bevoelkerungsschutz-2.html. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Hasell J, Mathieu E, Beltekian D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing. Accessed June 7, 2020.

Carrel P, Poltz J. It was the saltshaker: How Germany meticulously traced its coronavirus outbreak. The World Economic Forum COVID Action Platform. April 12, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/it-was-the-saltshaker-how-germany-meticulously-traced-its-coronavirus-outbreak. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Böhmer MM, Buchholz U, Corman VM, et al. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak in Germany resulting from a single travel-associated primary case: a case series. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2020;S1473-3099(20)30314-5. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30314-5. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Einblicke in die Analysen der Corona-Datenspende [Insights into the analysis of corona data donation]. Corona-Datenspende website. https://corona-datenspende.de/. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Böhmer MM, Buchholz U, Corman VM, et al. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak in Germany resulting from a single travel-associated primary case: a case series. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2020;S1473-3099(20)30314-5. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30314-5. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Busvine D, Rinke A. Germany flips to Apple-Google approach on smartphone contact tracing. Reuters. April 26, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-europe-tech/germany-flips-on-smartphone-contact-tracing-backs-apple-and-google-idUSKCN22807J. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Beaumont P, Connolly K. Covid-19 track and trace: what can UK learn from countries that got it right? The Guardian. May 21, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/21/covid-19-track-and-trace-what-can-uk-learn-from-countries-got-it-right. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Regalado A. Blood tests show 14% of people are now immune to covid-19 in one town in Germany. MIT Technology Review. April 9, 2020. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/04/09/999015/blood-tests-show-15-of-people-are-now-immune-to-covid-19-in-one-town-in-germany/. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Wie viele Menschen sind immun gegen das neue Coronavirus? Robert Koch-Institut startet bundesweite Antikörper-Studien. [How many people are immune to the new corona virus? Robert Koch Institute starts nationwide antibody studies]. [Press release]. Robert Koch Institute. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Service/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2020/05_2020.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Böhmer MM, Buchholz U, Corman VM, et al. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak in Germany resulting from a single travel-associated primary case: a case series. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2020;S1473-3099(20)30314-5. http://doi.org10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30314-5. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Hoehl S, Rabenau H, Ciesek S et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Returning Travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1278-1280. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2001899. Accessed June 8, 2020.

Plecher H. Median age of the population in Germany 1950-2050. Statista website. April 8 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/624303/average-age-of-the-population-in-germany/. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Daily Situation Report of the Robert Koch Institute. May 16, 2020. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/2020-05-16-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Daily Situation Report of the Robert Koch Institute. May 17, 2020. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/2020-05-17-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Mortality Risk of COVID-19. Our World in Data website. https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=ESP+DEU+USA+ITA+KOR. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Mortality Risk of COVID-19. Our World in Data website. https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid?country=ESP+DEU+USA+ITA+KOR. Accessed June 1, 2020.

Domestic occurrence status: Coronavirus Infection-19 Outbreak Status in Korea. Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare website. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/bdBoardList_Real.do?brdId=1&brdGubun=11&ncvContSeq=&contSeq=&board_id=&gubun=. Accessed June 8, 2020.

COVID-19 (Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2). Robert Koch Institute website. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/nCoV.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

COVID-19: Kriterien zur Entlassung aus dem Krankenhaus bzw. aus der häuslichen Isolierung [COVID-19: Criteria for discharge from hospital or from home isolation]. Robert Koch Institute website. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Entlassmanagement.html?nn=13490888. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Robert Koch Institute. Prävention und Management von COVID-19 in Altenund Pflegeeinrichtungen und Einrichtungen für Menschen mit Beeinträchtigungen und Behinderungen [Prevention and management of COVID-19 in elder care facilities and facilities for people with impairments and disabilities]. Berlin: Robert Koch Institute; 2020. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Alten_Pflegeeinrichtung_Empfehlung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed June 5, 2020.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance of COVID-19 in Long-Term Care Facilities in the EU/EEA, 19 May 2020. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-long-term-care-facilities-surveillance-guidance.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2020.

DIVI-Intensivregister website. https://www.intensivregister.de/#/index. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronik der bisherigen Maßnahmen [Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronology of measures taken]. German Federal Ministry of Health. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/en/coronavirus/chronologie-coronavirus.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronik der bisherigen Maßnahmen [Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Chronology of measures taken]. German Federal Ministry of Health. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/en/coronavirus/chronologie-coronavirus.html. Accessed June 8, 2020.

Connolly K. German doctors pose naked in protest at PPE shortages. The Guardian. April 27, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/27/german-doctors-pose-naked-in-protest-at-ppe-shortages. Accessed June 2, 2020.

The Editorial Board. Germany’s new coronavirus thinking. The Wall Street Journal. May 14, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/germanys-new-coronavirus-thinking-11589498695. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Coronavirus: Germany not alarmed by infection rate rise. BBC. May 12, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52632369. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Guest Authors (2020) - “Emerging COVID-19 success story: Germany's strong enabling environment” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-germany-2020' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-covid-exemplar-germany-2020,

author = {Guest Authors},

title = {Emerging COVID-19 success story: Germany's strong enabling environment},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2020},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-germany-2020}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.