How do countries measure immigration, and how accurate is this data?

Countries estimate how many people move in and out using censuses, surveys, and border records. How accurate are these numbers, and can they account for illegal migration?

Debates about migration are often in the news. People quote numbers about how many people are entering and leaving different countries. Governments need to plan and manage public resources based on how their own populations are changing.

Informed discussions and effective policymaking rely on good migration data. But how much do we really know about migration, and where do estimates come from?

In this article, I look at how countries and international agencies define different forms of migration, how they estimate the number of people moving in and out of countries, and how accurate these estimates are.

Migrants without legal status make up a small portion of the overall immigrant population. Most high-income countries and some middle-income ones have a solid understanding of how many immigrants live there. Tracking the exact flows of people moving in and out is trickier, but governments can reliably monitor long-term trends to understand the bigger picture.

Who is considered an international migrant?

In the United Nations statistics, an international migrant is defined as “a person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence for at least a year, so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence”.1

For example, an Argentinian person who spends nine months studying in the United States wouldn’t count as a long-term immigrant in the US. But an Argentinian person who moves to the US for two years would. Even if someone gains citizenship in their new country, they are still considered an immigrant in migration statistics.

The same applies in reverse for emigrants: someone leaving their home country for more than a year is considered a long-term emigrant for the country they’ve left. This does not change if they acquire citizenship in another country. Some national governments may have definitions that differ from the UN recommendations.

What about illegal migration?

“Illegal migration” refers to the movement of people outside the legal rules for entering or leaving a country. There isn’t a single agreed-upon definition, but it generally involves people who breach immigration laws. Some refer to this as irregular or unauthorized migration.

There are three types of migrants who don’t have a legal immigration status. First, those who cross borders without the right legal permissions. Second, those who enter a country legally but stay after their visa or permission expires. Third, some migrants have legal permission to stay but work in violation of employment restrictions — for example, students who work more hours than their visa allows.

Tracking illegal migration is difficult. In regions with free movement, like the European Union, it’s particularly challenging. For example, someone could move from Germany to France, live there without registering, and go uncounted in official migration records.2 The rise of remote work has made it easier for people to live in different countries without registering as employees or taxpayers.

A large 2024 study examined how to measure irregular migration, compiling and cross-referencing data from 20 countries, including the US.3 Because of the challenges I mentioned, these estimates are imperfect. However, they are the best approximation of the share of immigrants who lack legal status in different countries.

The chart below shows that irregular migrants are estimated to be a small minority in most high-income nations. The US stands out, with an estimated 22% of its immigrant population lacking legal status. In contrast, in the UK the share is 7%, in Germany 4%, in France 3%, and in the Netherlands 2%. These percentages were calculated by dividing the estimates of irregular migrants by the total immigrant population based on UN DESA data.

Migration statistics aim to include everyone, including those without legal status. These numbers are factored into population estimates, though experts recognize the limitations in achieving this. In the US, researchers combine census data with studies on coverage gaps and surveys from countries of origin to estimate how many people might be missed. To adjust for undercounted groups, they typically add 5% to 15%, depending on factors like age or how recently someone arrived.4

To give some context on the broader scale of illegal migration in Europe, Pew Research estimated that, in 2017, there were between 4 and 5 million migrants without legal status in the European Union.5 That represents about 5% of all immigrants and less than 1% of the total population, with nearly half of them in Germany and the UK (when the UK was still part of the EU).

The difference between immigration flows and stocks

Before I get into how migration numbers are estimated, it’s worth clarifying a few key terms.

First, statisticians talk about the stock of immigrants. This is the total number of immigrants living in a country at a given time. It’s a snapshot of how many foreign-born people have moved to a country.

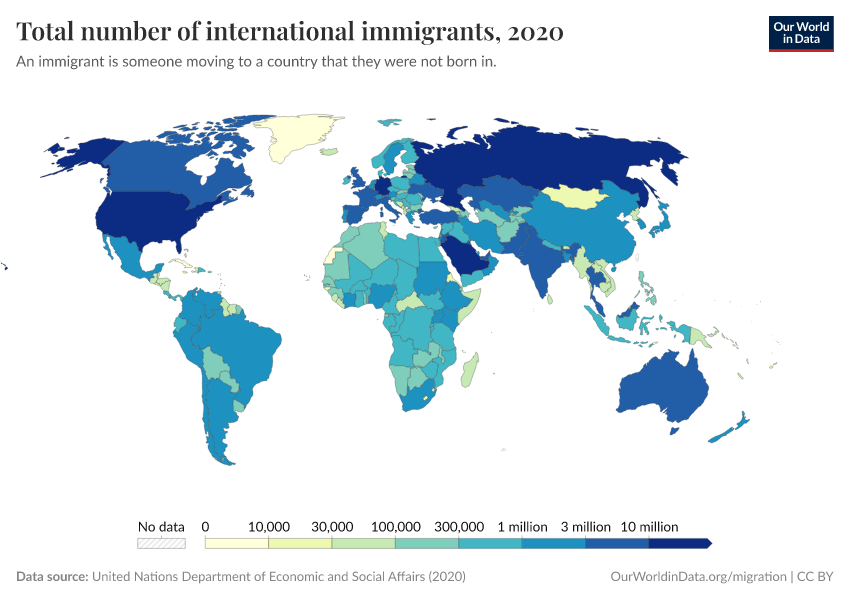

The chart below shows the UN’s estimates of the stock of immigrants. For example, the US has about 50 million immigrants, which means 50 million people who live in the US were not born there.

The second term is about the flow of migrants, which refers to changes over time. If people are moving into a country, they’re counted as immigrants by that country. If people are leaving, they will be counted as emigrants. The difference between the two is called net migration. This tells us how many more people have arrived minus how many have left during a period.

For instance, if 50,000 people arrive and 30,000 leave in one year, the net migration is 20,000.

The annual net migration rate is often expressed per 1,000 people in a country. So if the total population is 10 million, having a net migration of 20,000 gives an annual net migration rate of 2 migrants per 1,000 people. A negative net migration rate means that more people leave a country than enter it.

The chart below shows the net migration rate for 2023, indicating whether more people are moving into a country or leaving it. If a country is coloured blue, more people are moving in than out during that year. If it’s yellow or red, more people are leaving than arriving. For example, places like Canada and Australia have a lot more people moving in, while in some Balkan countries and South-East Asia, more people are moving out.

How are immigration stocks measured?

Most countries count their population every ten years with a census.

During a census, statisticians try to count people household by household, whether they are citizens or migrants with legal status or not.6 It’s a huge task, which is why it’s usually only done once a decade. This map shows which countries completed a population census in the past ten years as of 2023. Countries shaded in blue conducted a census, while those in orange did not.

While censuses give a fairly complete picture of the national population, gaps still need to be filled. In the most recent census in the UK, 3% of households did not respond, and it is more likely that people without legal status don’t fill out a census. Therefore, the UK’s Office of National Statistics has to make additional estimates by using information from other records.7

To keep track of changes between censuses, some countries, like the US, use yearly surveys, such as the Current Population Survey, to estimate how many immigrants are in the country. These surveys are less detailed than a census, but they help provide an idea of population changes in between the bigger counts.

Now, how do statisticians take all these national statistics and combine them to estimate global immigration numbers? The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs collects information from countries up to 2020.

For most countries, the UN’s migration data comes from population censuses (about 70% of the time). In other cases, it comes from population registers (17%) or surveys (13%). Most countries count immigrants as people born in another country (~80%), but some use citizenship (~20%), which can be based on where their parents or family are from.8

To provide estimates between census years, the United Nations Population Division (UNPD) uses methods called interpolation (filling gaps in data) and extrapolation (predicting future trends).

Getting reliable data is challenging in some places, especially in countries with limited resources or where conflicts are ongoing. The UN gathers data from 232 countries, territories, or regions. Most (87%) of these countries have provided at least some information about how many immigrants live there based on their last census. Many also share details about where immigrants come from (76%) and their age (71%).9

Census data is usually the best source for these numbers because it’s very detailed. However, since censuses are only conducted every ten years, it can be tricky for governments and media outlets to get up-to-date information. Additionally, they rarely address migration status or the type of visa the individual used to enter the country, making it even more challenging to estimate illegal immigration. Another challenge is that censuses usually only count immigrants, not emigrants (people leaving the country), and they don’t always record the exact year people moved or if they returned to their home country later.10

How are immigration flows measured?

Since censuses are only carried out every decade or so, they can’t be used to monitor immigration flows in a single year or even shorter periods.

How do countries estimate immigration flows?

They collect this information using surveys and different registration systems. For example, they count how many immigrants arrived in a year using records like residence permits, visas, asylum applications, and other immigration documents. Yet, some registration systems rely on people reporting when they move, which isn’t always done reliably.

Some countries, like the Netherlands or Japan, use population registers, which keep an updated record of who lives in the country by tracking changes such as births, deaths, and moves. When residents must register to live in a home or take up employment, tracking migration flows becomes much simpler and more accurate. However, only a minority of countries have these systems in place.11 For most, estimates must rely on piecing together data from various sources.

High-income countries have reasonable estimates of the number of people entering each year, including those without legal status. However, the reliability of these numbers varies by region and source. Some data points can be treated as reasonably exact counts, especially those based on census data. Most others, however, are estimates. The reliability of these estimates isn’t a simple yes-or-no; it depends on the specific question you’re trying to answer. This article aims to explain the different methods used to make these estimates. Knowing where estimates come from can help you decide if the data quality is good enough for your needs.

The numbers are less reliable for shorter periods, like a month or a quarter, or very recent data, so any small changes shouldn’t be taken too confidently. However, these records give a clearer picture of migration trends over longer periods, like multiple years. This is because long-term data is anchored to the data from the censuses.

Tracking emigration is more complex than monitoring immigration because people rarely report when they leave. This makes it difficult to know how long emigrants stay or if they return to their home countries. Plus, most countries don’t share immigration data, so if someone registers as an immigrant in one country, the country they left may not know.

At the global level, measuring immigration flows is challenging because most countries do not provide detailed data on people entering and exiting. In the United Nations World Population Prospects (UNWPP) methodology, net migration can be calculated directly using detailed records on immigration and emigration in countries where high-quality data is available.12

But net migration needs to be indirectly estimated in many cases. The UNWPP estimates combine census data with information on fertility and mortality to calculate population changes that cannot be explained by natural factors alone. This method, known as residual estimation, assumes that any unexplained population growth or decline is due to migration after making adjustments to correct for net coverage errors or data quality problems.

To ensure consistency at the global level, the UNWPP methodology applies small adjustments to net migration estimates for countries where data is uncertain. This process, called net migration balancing, ensures that the total global net migration equals zero.

One example: the United Kingdom

Finally, it might be worth looking at a country in more depth as an example. Here, I’ve taken the United Kingdom.

Regarding stock data, the UK’s census is the most important source. It is conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The latest census (from 2021) shows that 16% of the UK’s population of 67 million was born abroad.13

For flow data, the ONS estimated net migration (immigrants minus emigrants) to be 685,000 people in 2023. They provided an uncertainty interval suggesting the actual figure is likely between 564,000 and 744,000.14 This means the actual number could vary by nearly 18% from the estimate or by more than a hundred thousand people. And it could be even more, because the uncertainty interval cannot quantify accuracy as well as confidence intervals.

Estimating migration flows to and from the UK is challenging, partly due to the absence of a population register — a point highlighted in the book Bad Data by migration expert Georgina Sturge. In contrast, countries like Japan and Spain use population registers to track residents more accurately. The UK has to gather information from various government records without a single system or a way to quickly match individuals across these datasets. This is even harder for British nationals, whose estimates still rely on old survey methods, and foreign nationals with indefinite leave to remain, including EU nationals with settled status.

Recently, the UK also changed its migration measurement methods to improve accuracy.15 Previously, estimates were based on a survey of people entering and leaving the country, which led to significant errors, such as overstating how many students overstayed their visas in the early 2010s.16

Because of the uncertainty, it’s hard to be certain about recent changes in yearly migration numbers. For example, the estimated decrease in net migration from 2022 to 2023 was 79,000. But with these uncertainty intervals, the actual drop could easily be tens of thousands more or less. This shows how small shifts in estimates can lead to different interpretations of migration trends.

Overall, not having a population register likely makes UK immigration statistics less accurate than in countries like the Netherlands. Still, the UK is a high-income country, an island, and has a well-developed statistical office. The margin of error for migration estimates could be significantly higher in countries with fewer resources, less developed systems, and land borders that are harder to control. This means migration data in lower-income countries is often less reliable and more uncertain.

While migration data isn't perfect and can be imprecise in the short run, especially for specific groups or due to outdated methods, they still offer a solid foundation for understanding broader trends over time. Understanding how migration data is collected and its limitations is vital for anyone engaging with migration topics. Knowing how this data is gathered, along with its uncertainties, helps us assess how well it can inform decisions and track long-term trends.

Endnotes

United Nations (2020). Handbook on Measuring International Migration through Population Censuses, page 7, paragraph 23.

France does not have a population register. (Sourced from UNECE).

Kierans, D. and Vargas-Silva, C. (2024). The Irregular Migrant Population of Europe. Link

Sourced from Pew Research Center

This is about the European Union and the European Free Trade Association countries.

Sourced from US Census

Sourced from ONS

Sourced from United Nations Methodology Report 2020, p.4

Sourced from United Nations Methodology Report 2020, p.5

Sourced from International migration under the microscope, Willekens et al. 2016, Science, p.897, right-hand side column

Sourced from Statistics Norway

Sourced from United Nations World Population Prospects Methodology Report 2024, from p.25

However, the ONS has indicated that it may not hold a census in 2031, leaving questions about how future estimates will be validated without this crucial dataset for accuracy checks.

UK migration expert Georgina Sturge clarifies that the “uncertainty intervals” differ from confidence intervals. They are derived through simulation studies, where 95% of the simulated intervals will be expected to include the true value, provided the simulations have adequately captured the main sources of uncertainty. The challenge, however, lies in the potential for unknown variables affecting the outcome, as the model's reliability is assessed only by re-running it with small adjustments to a restricted set of assumptions. Georgina Sturge is a statistician on migration and justice for the House of Commons Library and the Author of Bad Data, How Governments, Politicians and the Rest of Us Get Misled by Numbers.

Sourced from Commons Library

Sourced from The Guardian

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Simon van Teutem and Tuna Acisu (2024) - “How do countries measure immigration, and how accurate is this data?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260225-004721/countries-measure-immigration-accurate-data.html' [Online Resource] (archived on February 25, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-countries-measure-immigration-accurate-data,

author = {Simon van Teutem and Tuna Acisu},

title = {How do countries measure immigration, and how accurate is this data?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2024},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260225-004721/countries-measure-immigration-accurate-data.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.