Homicide data: how sources differ and when to use which one

There are several ways to measure homicides. What approaches do different sources take? And when is which approach best?

Measuring homicides across the world helps us understand violent crime and how people are affected by interpersonal violence.

But measuring homicides is challenging. Even homicide researchers do not always agree on whether the specific cause of death should be considered a homicide. Even when they agree on what counts as a homicide, it is difficult to count all of them.

In many countries, national civil registries do not certify most deaths or their cause. Besides lacking funds and personnel, a body has to be found to determine whether a death has happened. Authorities may also struggle to distinguish a homicide from a similar cause of death, such as an accident.

Law enforcement and criminal justice agencies collect more data on whether a death was unlawful — but their definition of unlawfulness may differ across countries and time.

Estimating homicides where neither of these sources is available or good enough is difficult. Estimates rely on inferences from similar countries and contextual factors that are based on strong assumptions. So how do researchers address these challenges and measure homicides?

In our work on homicides, we provide data from five main sources:

- The WHO Mortality Database (WHO-MD)1

- The Global Study on Homicide by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)2

- The History of Homicide Database by Manuel Eisner (20033 and 20144)

- The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)5

- The WHO Global Health Estimates (WHO-GHE)6

These sources all report homicides, cover many countries and years, and are frequently used by researchers and policymakers. They are not entirely separate, as they partially build upon each other.

You can delve into the specific charts — absolute numbers and homicide rates, sometimes also disaggregated by sex and age group — on our topic page on homicides.

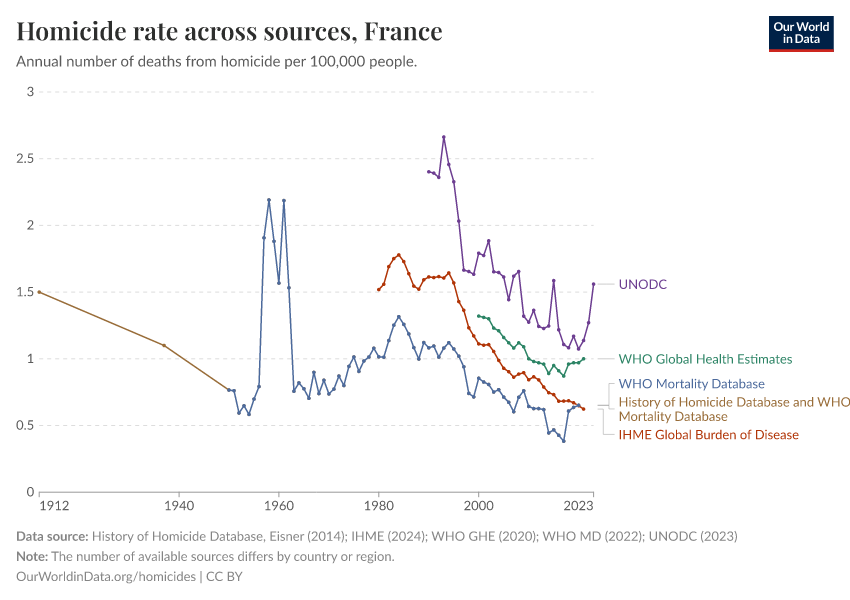

Reassuringly, despite their different approaches, the sources tend to agree on the major patterns in the number of homicides: they distinguish between countries where homicide rates are high, such as Brazil and South Africa, and countries where homicides are rare, such as Japan and Oman.

But they do not always agree completely. Any ranking of countries from highest to lowest rates will often vary. For some countries, they reach very different conclusions on the frequency of homicides.

The chart illustrates how sources can differ: they agree that homicides in France have become less frequent in recent decades. But they diverge in how frequent they exactly were and are.

Why do these estimates differ? And is there any best approach? This article summarizes the key similarities and differences between the sources and discusses when each source is best.

How do different sources define homicide?

In this table and the ones that follow, we summarize how the definition of homicides in different sources differ and how they are measured.7

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

As you see, the sources use similar definitions of what constitutes a homicide. They all define homicide as the intentional killing of a person by another.

Where they differ is in whether they specify whether the intent only includes causing death or also serious injury and whether the killing must be unlawful.

With their focus on intentionality, the sources differ from how homicides are often commonly understood: that they do not have to be intentional, but can be accidental or reckless.

What years and countries do sources cover?

The sources also differ in what years and countries they cover.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

Almost all sources cover the recent past. But they differ in how far they go back in time: some go back a few decades, while the WHO Mortality Database covers some countries as early as 1950, and the History of Homicide Database goes back as far as the late Middle Ages (while not covering the most recent years).

Almost all sources cover large parts of the world. The WHO Mortality Database especially covers countries in Europe and the Americas, and the History of Homicide Database exclusively covers countries and territories in Europe.

How do different sources go about identifying homicides?

The sources also differ in how they go about identifying homicides.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

The WHO Mortality Database relies exclusively on data from national civil registries, which collect death certificates with the identified cause.

Because many deaths and their causes are not registered, other approaches use additional data from national law enforcement and criminal justice authorities, which collect reports of their criminal investigations. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is the leading collector of this data, and others reuse it in their datasets. The History of Homicide Database also uses such police data but often gets it from historical studies.

Finally, for countries and years for which no direct data is available, or the data quality is poor, some approaches combine these mortality and police statistics with contextual data (such as the young male population and alcohol consumption) to estimate the number of homicides.8

How do sources work to collect the relevant data?

The following tables summarize how the sources address the specific challenges of measuring homicides. The first challenge is to make their assessments valid — to actually measure what they want to measure.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

For the WHO Mortality Database, this means only providing the best data available. It only uses data from civil registries, as those have a highly-standardized definition of homicide. It excludes law enforcement and criminal justice data, because criteria of unlawfulness may differ across countries and time. It still only includes this civil registry data if it identifies the cause of death for at least 65% of cases. And it avoids making any adjustments to the data, or producing statistical estimates for countries and years without any reliable data because it finds the necessary assumptions too strong to make them.

For other sources, however, measuring what they want to measure means providing data for as many countries and years as possible, as long as the data still seems reasonable. The Global Burden of Disease and the Global Health Estimates use many different sources of information, including police statistics and information on similar countries and contextual factors. This information is then used as input into statistical models that produce estimates for all countries across recent decades.

Other approaches seek to balance these goals of using the best data and covering many countries and years. UNODC and the History of Homicide Database use law enforcement and criminal justice data in addition to statistics from civil registries and make small adjustments to the data. But they refrain from estimating homicides for countries with no or poor data.

How do sources work to make the assessments precise?

The sources are also concerned with making their assessments precise and reliable.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

Some approaches only use civil registry data or prioritize it over other primary sources, as the underlying reports by medical personnel are exact about the cause of death. UNODC instead favors criminal justice data, because it considers law enforcement and related agencies to be more reliable in their assessments of whether a killing was unlawful.

Several approaches also disaggregate their data to make it more precise: they split their estimates by the victim’s sex, their age group, and sometimes also by weapon, the homicide’s context, and the characteristics of the perpetrator.

How do sources work to make the data comparable?

The approaches also face the challenge of how to make the data comparable across countries and time.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

Some use a standardized definition of homicide across their primary sources. The intention is to reduce the likelihood that national differences in what killings are classified as a homicide lead to cross-national numbers that are not comparable.

Others make adjustments to the primary data to make the different primary sources correspond to one another. For example, they adjust the numbers from vital registries, as those tend to undercount homicides relative to law enforcement and criminal justice statistics.

And some approaches use information from similar countries and contextual information to come up with comparable estimates, even for countries for which no or only poor data is available.

How are the remaining differences between primary sources dealt with?

Almost all approaches then work to address any remaining differences between primary sources, even if they do so differently.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

For some, reconciling differences between primary sources is not a big concern. The WHO Mortality Database has no different estimates to reconcile because it exclusively uses one primary source per country, the national civil registry. The History of Homicide Database also rarely has differing estimates, because they refer to different areas within countries and territories.

But the approaches that rely on different primary sources face the challenge of reconciling them. Sometimes, they do so by considering their respective quality and prioritizing the ones that seem more authoritative, or provide estimates that seem more plausible.

Some also partially sidestep the issue by sharing uncertainty ranges alongside their best estimates. By doing this, they avoid forcing themselves to eliminate all uncertainty and possibly biasing their estimates.

Finally, UNODC asks national authorities to review their data and adjustments.

How do sources work to make the data accessible and transparent?

Finally, the sources all take steps to make their data accessible and the underlying measurement transparent. All approaches publicly release their data, and most make the data straightforward to download and use on their respective websites.

| WHO Mortality Database |

|

| UN Office on Drugs and Crime |

|

| History of Homicide Database |

|

| IHME Global Burden of Disease |

|

| WHO Global Health Estimates |

|

All also share their coding procedures. But some provide many more details than others.

Furthermore, some discuss the data’s quality in detail and reflect on how complete and comparable the data is across countries and time.

The best source depends on your questions

There is no single ‘best’ approach to measuring homicides. All of the sources put a lot of effort into measuring them in ways that are useful to researchers, policymakers, and interested citizens.

The most appropriate source depends on what question you want to answer. It is the one that captures the countries and time you are interested in, and meets the quality standards you set.

If you are interested in very long-term trends in homicides, the History of Homicide Database is best.

If you want to study as many countries as possible during recent decades and are willing to rely on strong assumptions about how much you can infer from neighboring countries and contextual factors, the IHME Global Burden of Disease and the WHO Global Health Estimates are best.

If you instead want to set a strict standard for data quality and are willing to disregard any data that does not meet this high standard, the WHO Mortality Database is best.

And if you are interested in striking a balance between covering many countries and years and using high-quality data, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime is best.

Even if you have a preferred source, it can still be useful to see what other sources show and where they agree and differ.

This means that having several approaches to measuring homicides is not a flaw but a strength: it gives us different tools to understand the past, current state, and possible future of homicides around the world.

If you want to explore and compare the data from each of these sources, you can do so on our Homicides topic page.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maurice Dunaiski, Doris Ma Fat, Edouard Mathieu, Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Eve Wool for reading drafts of this text and providing very helpful comments.

Endnotes

World Health Organization. 2023. World Health Organization Mortality Database Visualization Portal. https://platform.who.int/mortality. Accessed on 2023-01-03.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022. UNODC Research Data Portal. Intentional Homicides.

Eisner, Manuel. 2003. Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime. Crime and Justice 30: 83-142.

Eisner, Manuel. 2014. From Swords to Words: Does Macro-Level Change in Self-Control Predict Long-Term Variation in Levels of Homicide? Crime and Justice 43: 65-134.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396: 1204-1222.

World Health Organization. 2020. Global Health Estimates 2019: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2019. Geneva: World Health Organization.

This article draws on several very helpful other articles summarizing and reviewing some of the datasets, as well as the datasets’ codebooks and descriptions:

Eisner, Manuel. 2003. Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime. Crime and Justice 30: 83-142.

Eisner, Manuel. 2008. Modernity Strikes Back? A Historical Perspective on the Latest Increase in Interpersonal Violence (1960-1990). International Journal of Conflict and Violence 2(20: 288-316.

Eisner, Manuel. 2014. From Swords to Words: Does Macro-Level Change in Self-Control Predict Long-Term Variation in Levels of Homicide? Crime and Justice 43: 65-134.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396: 1204-1222.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396: Supplementary appendix 1.

Kanis, Stefan, Steven Messner, Manuel Eisner, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2017. A Cautionary Note about the Use of Estimated Homicide Data for Cross-National Research. Homicide Studies 21(4): 312-324.

Rogers, Meghan, and WIlliam Pridemore. 2023. A Review and Analysis of the Impact of Homicide Measurement on Cross-National Research. Annual Review of Criminology 6: 447-470.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2019. Methodological Annex to The Global Study on Homicide 2019.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022. UNODC Research Data Portal. Intentional Homicides Metadata information.

World Health Organization. 2020. WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000-2019.

World Health Organization. nd. Estimates of number of homicides.

This means that the resulting homicide estimates cannot be used to study whether these contextual factors are causes of homicides, because the estimates will be associated with them by construction.

For more information, see: Kanis, Stefan, Steven Messner, Manuel Eisner, and Wilhelm Heitmeyer. 2017. A Cautionary Note about the Use of Estimated Homicide Data for Cross-National Research. Homicide Studies 21(4): 312-324.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Bastian Herre and Fiona Spooner (2023) - “Homicide data: how sources differ and when to use which one” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260211-174736/homicide-data-how-sources-differ-and-when-to-use-which-one.html' [Online Resource] (archived on February 11, 2026).BibTeX citation

@article{owid-homicide-data-how-sources-differ-and-when-to-use-which-one,

author = {Bastian Herre and Fiona Spooner},

title = {Homicide data: how sources differ and when to use which one},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20260211-174736/homicide-data-how-sources-differ-and-when-to-use-which-one.html}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.