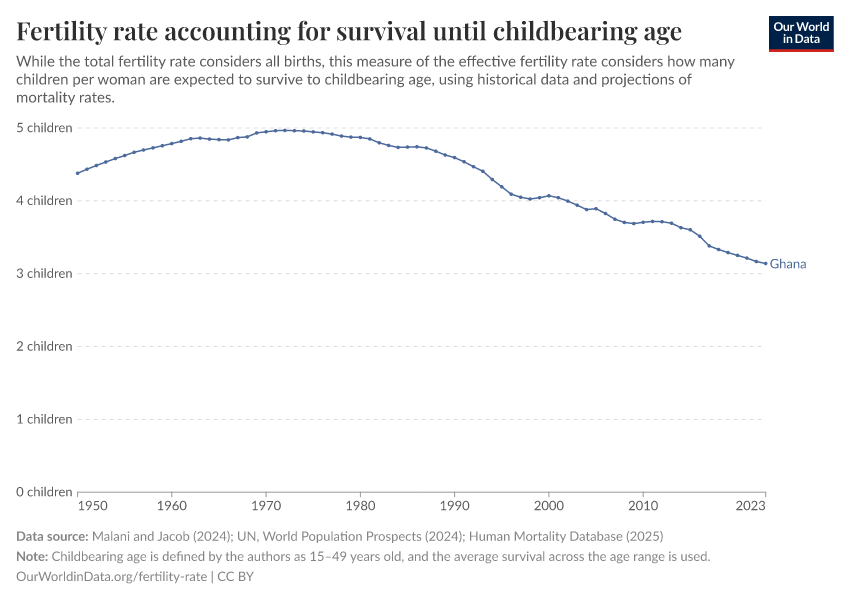

Fertility rate accounting for survival until childbearing age

About this data

About this data

Sources and processing

This data is based on the following sources

How we process data at Our World in Data

All data and visualizations on Our World in Data rely on data sourced from one or several original data providers. Preparing this original data involves several processing steps. Depending on the data, this can include standardizing country names and world region definitions, converting units, calculating derived indicators such as per capita measures, as well as adding or adapting metadata such as the name or the description given to an indicator.

At the link below you can find a detailed description of the structure of our data pipeline, including links to all the code used to prepare data across Our World in Data.

Notes on our processing step for this indicator

For a given cohort year, we estimate the cumulative survival probability for a person to reach each age from 0 to 49. For example, the probability of a person born in 2000 reaching age 15, 16, 17, and so on up to 49. We have used HMD data for years before 1950, and UN's for years after 1950 (including).

We then estimate the Effective Fertility Rate (EFR) for each age group by multiplying the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) by the cumulative survival probability. The EFR for a given age gives us an approximation of the average number of children from a woman that will live long enough to reach that age.

For years before 1950, we have used HMD data, which does not provide TFR values. Instead, we have used an approximation of the TFR based on births and female population (in reproductive ages), as suggested by Jacob and Malani (2024).

The Reproductive Effective Fertility rate (EFR) is the average of the EFR over all reproductive ages (15-49).

Note that the Reproductive Effective Fertility rate (EFR) is an approximation of the number of daughters, so it uses the total fertility rate of female children, or equivalently, the TFR weighted by the sex ratio at birth.

So we have that: EFR_repr = (TFR * mean(EFR)) / (1 + SRB), where SRB is the male-to-female ratio and the mean is taken over all reproductive ages (15-49).

This indicator is scaled by the sex ratio to allow easy comparability with the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) and the Labor Effective Fertility rate (EFR_labor).

Read more details in the author's paper: https://www.nber.org/papers/w33175

Reuse this work

- All data produced by third-party providers and made available by Our World in Data are subject to the license terms from the original providers. Our work would not be possible without the data providers we rely on, so we ask you to always cite them appropriately (see below). This is crucial to allow data providers to continue doing their work, enhancing, maintaining and updating valuable data.

- All data, visualizations, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

Citations

How to cite this page

To cite this page overall, including any descriptions, FAQs or explanations of the data authored by Our World in Data, please use the following citation:

“Data Page: Fertility rate accounting for survival until childbearing age”, part of the following publication: Saloni Dattani, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, and Max Roser (2025) - “Fertility Rate”. Data adapted from Malani and Jacob, United Nations, Human Mortality Database. Retrieved from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251022-222946/grapher/effective-fertility-rate-children-per-woman-who-are-expected-to-survive-until-childbearing-age.html [online resource] (archived on October 22, 2025).How to cite this data

In-line citationIf you have limited space (e.g. in data visualizations), you can use this abbreviated in-line citation:

Malani and Jacob (2024); UN, World Population Prospects (2024); Human Mortality Database (2025) – processed by Our World in DataFull citation

Malani and Jacob (2024); UN, World Population Prospects (2024); Human Mortality Database (2025) – processed by Our World in Data. “Fertility rate accounting for survival until childbearing age” [dataset]. Malani and Jacob, “A New Measure of Surviving Children that Sheds Light on Long-term Trends in Fertility”; United Nations, “World Population Prospects”; Human Mortality Database, “Human Mortality Database” [original data]. Retrieved January 15, 2026 from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20251022-222946/grapher/effective-fertility-rate-children-per-woman-who-are-expected-to-survive-until-childbearing-age.html (archived on October 22, 2025).