Mortality in the past: every second child died

The chances that a newborn survives childhood have increased from 50% to 96% globally. How do we know about the mortality of children in the past? And what can we learn from it for our future?

A child dying is one of the most dreadful tragedies one can imagine. We all know that child deaths were more common in the past. But how common? How do we know? And what can we learn from our history?

Archeologists and historians have brought together data from many places and time periods across the world which lets us piece together a picture of our past.

Sweden is a country that has particularly good historical demographic data. It was the first country to establish an office for population statistics: the Tabellverket, founded in 1749. Going back to their records we can look up the child mortality at the time. During the first three decades of the existence of the statistical office — the period from 1750 to 1780 — their data tells us that 40% of children died before the age of 15.1

During the same period, the mortality rate was about 45% in France, and in Bavaria, about half of all children died. At that time, the average couple had more than 5, 6, or even 7 children, which meant that most parents saw several of their children die.2

Was this unusual? Was the death rate in Europe particularly high at that specific time?

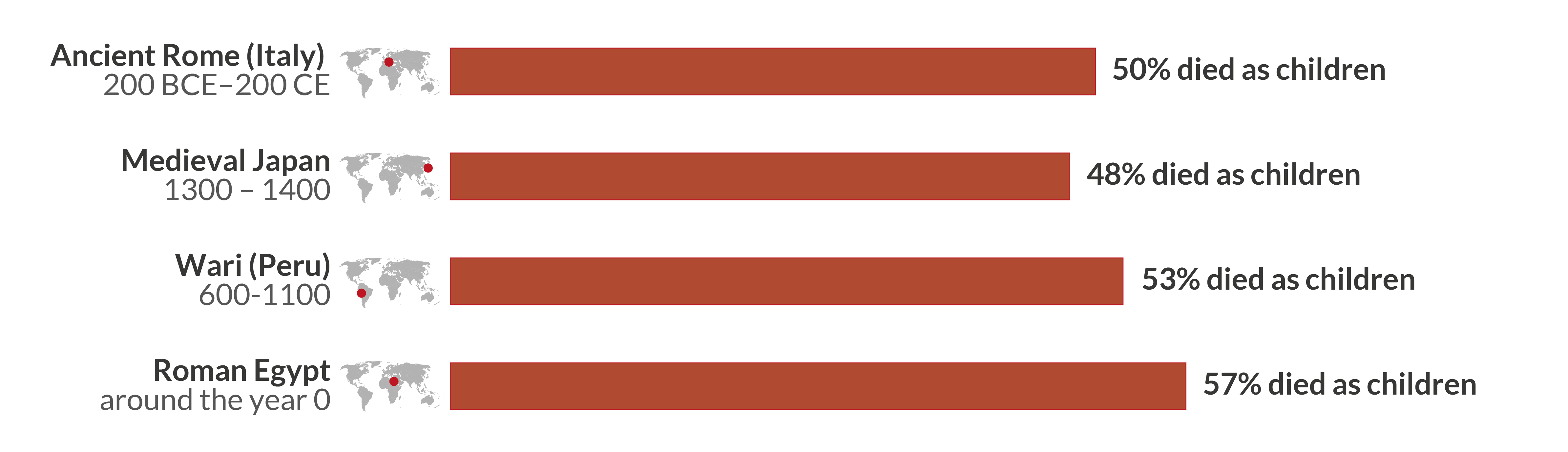

We can look at research for other places and time periods.

Based on skeletons found in the South of modern-day Peru, paleodemographers can estimate the mortality of children who were born two millennia ago. The records suggest a similar figure: almost half of all children died before the end of puberty.3

A burial site on the Spanish island of Mallorca offers us a view on child mortality in Europe during the Iron Age. Based on the skeletons found in Mallorca, researchers again found that about half of all children did not survive.4

And the same is also true in very different regions and different periods.

Researchers also collected data about hunter-gatherer societies. The 17 different societies include paleolithic and modern-day hunter-gatherers and the mortality rate was high in all of them. On average, 49% of all children died.5 At the end of this article, you can find more details about the available evidence for the mortality rates of children in hunter-gatherer societies.

The mortality of children over the long-run

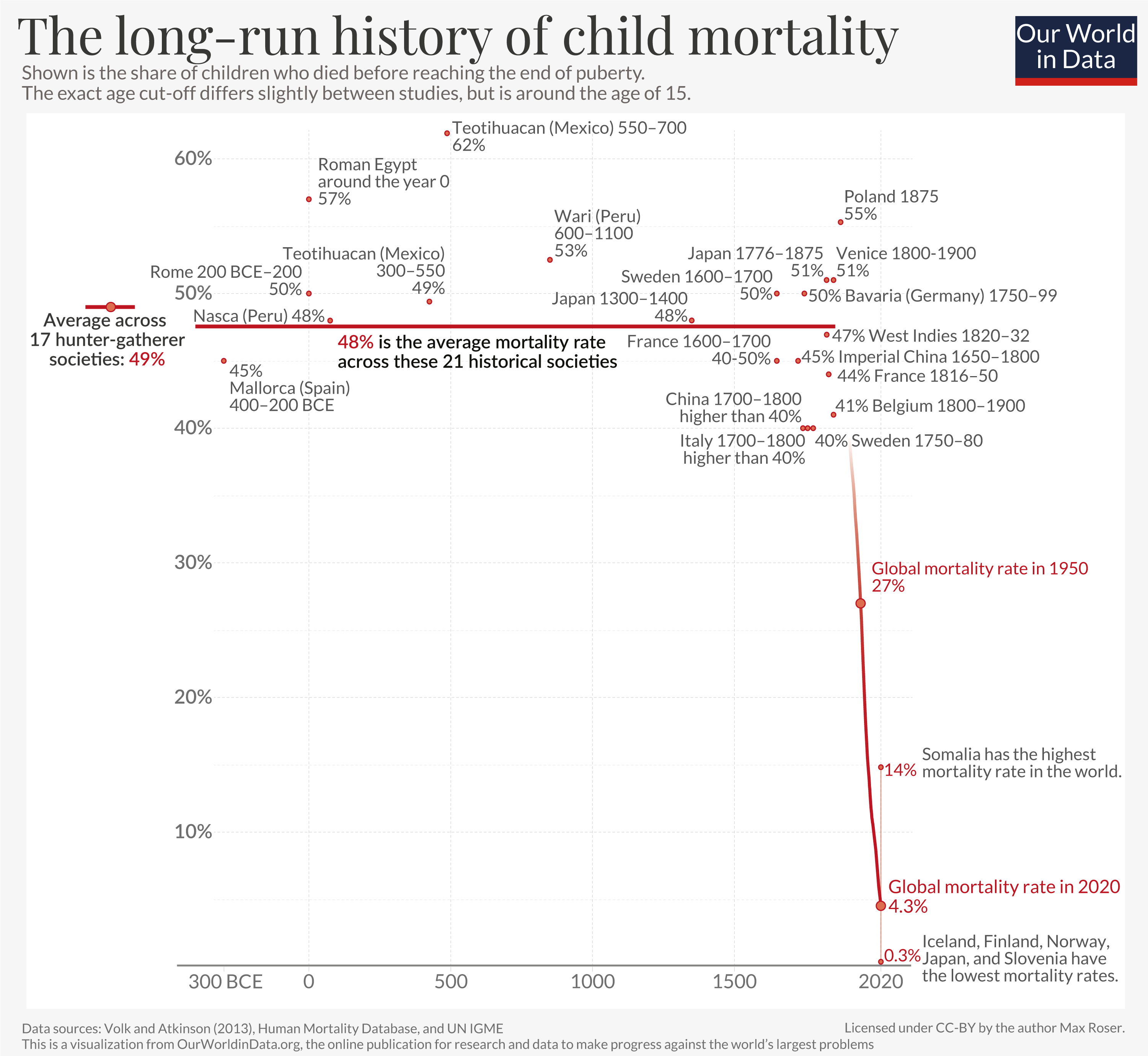

Let’s take all the historical estimates of child mortality and combine them with global data for recent decades to see what this tells us about humanity’s history.6

What is striking about the historical research is how similar child mortality rates were across a wide range of very different historical cultures: No matter where in the world a child was born, about half of them died.

Everyone failed to make progress

Tens of billions of children died.7 Billions of parents mourned helplessly when they saw their children dying.

Despite the relentless suffering, no one was able to do much about it.

The chart speaks about societies that lived thousands of kilometers away from each other, separated by thousands of years of history, and yet they all suffered the same pain. Whether in Ancient Rome, in hunter-gatherer societies, in the pre-Columbian Americas, in Medieval Japan or Medieval England, in the European Renaissance, or in Imperial China, every second child died.

While some societies were better off than others, the differences were small. Generation after generation was born into societies that struggled against poverty, hunger, and disease and there is no indication that any society made any substantial and sustained progress against those problems. Substantial progress against child mortality is a recent achievement everywhere.

It is not that people in the past didn’t try to make progress against early death and disease. They tried, of course.8 Healers and doctors had a high status in societies. And people often took on great pain and costs in the hope of improving their children’s health.

The “most common procedure performed by surgeons for almost two thousand years” in Europe was bloodletting. The pain this practice caused makes clear just how desperate people were to achieve any health improvements. The fact that it not only offered no benefits but that it was indeed harmful to the patients makes clear just how unsuccessful humanity was for most of its history.

All were suffering as they saw their children die, yet none of them were able to do anything about it.

The key insight for me is that progress is not natural. It is hard. Even against some of the largest problems — the unrelenting death of children — thousands of generations failed to make any progress.

Are these high historical mortality rates plausible?

The historical studies of child mortality don’t provide a full picture of our ancestors' past. They are snapshots of some moments in the long history of our species. Could they mislead us to believe that mortality rates were higher than they actually were?

There is another piece of evidence to consider that suggests the mortality of children was, in fact, very high: birth rates were high, but population growth was close to zero.

If every couple has, on average, four children, the population size would double each generation. But while we know that couples had on average, many more children than four, the population did not double with each generation.9 In fact, population sizes barely changed at all.

A high number of births without a rapid increase in population can only be explained by one sad reality: a high share of children died before they could have children themselves.

If anything, the mortality rates shown in the chart above probably underestimate the true mortality of children. Volk and Atkinson, the two researchers who gathered most of these studies, caution that these historical mortality rates “should be viewed as conservative estimates that generally err toward underestimating actual historic rates”.10 The first reason is that death records were often not produced for children, especially if children died soon after birth. A second reason is that child burial remains, another important source, are often incomplete “due to the more rapid decay of children's smaller physical remains and the lower frequency of elaborate infant burials”.11

The mortality of children today

The chart above also shows the dramatic progress that was recently achieved. Most children in the world still died at extremely high rates well into the 20th century. Even as recently as 1950 – a time that some readers might well remember – one in four children died globally.

More recently, during our lifetimes, the world has achieved an entirely unprecedented improvement. In a brief episode of human history, the global death rate of children declined from around 50% to 4%.

After millennia of suffering and failure, the progress against child mortality is, for me, one of the greatest achievements of humanity.

This is not an improvement that is only achieved by a few countries. The rate has declined in every single country in the world.

The map shows the latest available data for mortality up to the age of 15. In several countries the rate has declined to about 0.3%, a mortality rate that is more than 100-times lower than in the past. This was achieved in just a few generations. Progress can be fast.

In the richest parts of the world child deaths have become very rare, but differences across countries are high. Somalia – on the Horn of Africa – is the country with the highest rate, 14% of newborns die as children.

The fact that several countries show that it is possible for 99.7% of children to survive shows us what the world can aspire to. Global health has improved, and it is on us to make sure that this progress continues to bring the daily tragedy of child deaths to an end.

Our ancestors could have surely not imagined what is reality today. Let’s make it our goal to give children everywhere the chance to live a long and healthy life.

An earlier version of this article was published in June 2019.

Endnotes

As explained in the following footnote, this data is available from the Human Mortality Database.

Regarding the number of children that people had, the metric that I would ideally need here is the average number of children per woman (or per couple). This is sometimes reported as ‘average family size’, but I was not able to find this data. However, I could find data on the total marital fertility rate.

The sources for both the number of children and the rate of deaths for the three countries are the following:

Sweden: A total marital fertility rate of 7.62 children per married woman is reported in Table II (page 40) in M. Anderson (Ed.) (1996) – Population Change in North-Western Europe, 1750–1850. Extramarital children were rare in Sweden at the time. Anderson estimates it at 2%.

The under-15 mortality rate is taken from the Human Mortality Database and corresponds to the average of the annual observations between 1750 to 1780.

Bavaria, Germany: This data is taken from John Knodel’s research: John Knodel (1970) – ‘Two and a Half Centuries of Demographic History in a Bavarian Village.’ In Population Studies 24, no. 3 (1 November 1970): 353–76.

According to his study, married women had, on average 5.6 children and saw, on average, almost three (2.8) of their children die before they were 15 years old. Knodel also includes data for an earlier period but cautions against relying on it, writing: “The figure shown for couples married between 1692 and 1749 is undoubtedly spuriously high, resulting from the frequent omission of infant and child deaths from the parish registers during the period.” Knodel suggests that even the data after 1750 (which is shown here) is likely an underestimate of the true mortality.

France: In France, the average married woman had about 8 children in the period 1740 to 1769. This is the total marital fertility rate taken from Table II (page 40) in M. Anderson (Ed.) (1996) – Population Change in North-Western Europe, 1750–1850.

Youth mortality rates for France are reported in Volk and Atkinson. For the period 1600-1700, the authors report an estimate of 40-50%. They also present an estimate for the period 1816-50 when the mortality rate was 44%.

This research is carried out in the areas of Pueblo Viejo, Cahuachi, Estaqueria, and Atarco in the Nasca Valley.

The mortality is quoted after Anthony A.Volk Jeremy A. Atkinson (2013) – Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. In Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 34, Issue 3, May 2013, Pages 182-192.

The original paper is Drusini, A. G., Carrara, N., Orefici, G., & Bonati, M. R. (2001). Paleodemography of the Nasca valley: Reconstruction of the human ecology of the southern Peruvian coast. Homo, 52, 157–172.

This research is carried out in several sites on the S’Illot des Porros in Mallorca.

The mortality is quoted after Anthony A.Volk Jeremy A. Atkinson (2013) – Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. In Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 34, Issue 3, May 2013, Pages 182-192.

The original paper is Alesan, A., A. Malgosa, and C. Simó (1999) – Looking into the Demography of an Iron Age Population in the Western Mediterranean. I. Mortality. In American Journal of Physical Anthropology 110, no. 3 (November 1999): 285–301. The life expectancy at birth was 23 years.

For details, see the paper Anthony A.Volk Jeremy A.Atkinson (2013) – Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. In Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 34, Issue 3, May 2013, Pages 182-192.

When relying on evidence from modern hunter-gatherers, one needs to be cautious of how representative these societies are of those in the past. This is because recent hunter-gatherers might have been in exchange with surrounding societies and “often currently live in marginalized territories”, as the authors say. Both of these could matter for mortality levels so that the mortality rates are higher or lower than in historical times.

To account for this, Volk and Atkinson have attempted to include only hunter-gatherers that are best representative of the living conditions in the past; they limited their sample “only to those populations that had not been significantly influenced by contact with modern resources that could directly influence mortality rates, such as education, food, medicine, birth control, and/or sanitation.”

All but one of these studied societies in Volk and Atkinson are modern hunter-gatherers. The study on mortality rates of paleolithic hunter-gatherers finds a higher youth mortality rate: 56% did not survive until puberty.

In the literature on global health and modern health statistics, the most commonly studied age-cutoff is the age of five and the share of children dying before they are five years old is referred to as ‘child mortality.’ A low age cutoff makes some sense because the mortality in early childhood is typically substantially higher than in late childhood. At the same time, I also do believe it is actually wrong to exclude the deaths of children older than five from the data on child mortality.

A focus on the first five years gives only a partial view of the mortality of children. Childhood does not end at the age of five, and in this article, I’m relying on a more common definition of childhood and am considering all deaths up to the end of puberty or up to the age of 15. Which cutoff is used varies between the different studies on which this account is based.

A higher cut-off has the additional advantage that it becomes possible to connect with historical and archaeological research on the mortality of children. Especially in archeological records, it is not possible to determine the precise age at which a child died, but it is possible to differentiate between a child and an adult.

The researchers Anthony Volk and Jeremy Atkinson, on whose research I am primarily relying here, have brought together most of the historical estimates I am reporting here. Their literature search focused on the share of children who died before reaching “approximate sexual maturity at age 15”.

Anthony A. Volk and Jeremy A. Atkinson (2013) — Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. In Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 34, Issue 3, May 2013, Pages 182-192. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1090513812001237#s0015

Modern data is taken from the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). This data is published at childmortality.org

(Note that Volk and Atkinson refer to the mortality up to “approximate sexual maturity” as “child mortality”, while I am following the established language in global health statistics where child mortality is reserved for mortality up to the age of five.)

In my article on our long-term history and future, I brought together sources suggesting that a best-guess-estimate of the total number of humans ever born (before 2020) is about 117 billion. About 102 billion were born before 1850, according to demographers Toshiko Kaneda and Carl Haub (see previous link for the sources).

Applying a child mortality rate of 50% for all births before 1850 means that a bit more than 50 billion children died throughout human history. This is, of course, a rough estimate, but it gives us some idea of just how many children died.

Despite the great pain caused by poor health and early death, humanity discovered extremely few medical remedies and practices that were effective over the course of hundreds of generations.

While the rate of discoveries was extremely slow, there were certainly some breakthroughs that were relevant in the context of the time. One such example is that from the bark of the Cinchona tree, Quinine was extracted, which was effective in treating malaria. For other drugs, see Wikipedia’s List of drugs by year of discovery, which includes some other remedies.

We discuss this in more detail here and also in the first footnote of this article. From 10,000 BCE to 1700, the world population grew by only 0.04% annually.

Anthony A.Volk Jeremy A. Atkinson (2013) – Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. In Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 34, Issue 3, May 2013, Pages 182-192.

See also M.E. Lewis (2007) – The bioarchaeology of children. Cambridge University Press, NY.

The Indian Knoll site was investigated by Francis Johnston and Charles Snow C.E. Snow. See F.E. Johnston, C.E. Snow (1961) – The reassessment of the age and sex of the Indian Knoll skeletal population: Demographic and methodological aspects. In American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 19, pp. 237-244.

And also Indian Knoll skeletons. The University of Kentucky, Reports in Anthropology, Vol. IV, No. 3, Part 11 University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, KY (1948)

The 28% infant mortality rate is reported in Volk and Atkinson based on Trinkaus (1995).

Erik Trinkaus (1995) – Neanderthal mortality patterns. Journal of Archaeological Science, 22 (1995), pp. 121-142. Online here https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440395801707

Chamberlain (2006) also reports very high mortality rates for subadult Neanderthals (Homo Neanderthalensis). See: Andrew T. Chamberlain (2006) – Demography in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology).

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Max Roser (2023) - “Mortality in the past: every second child died” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-child-mortality-in-the-past,

author = {Max Roser},

title = {Mortality in the past: every second child died},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2023},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.