Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?

Globally, we emit around 50 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases yearly. Where do these emissions come from? We take a look, sector-by-sector.

We need to rapidly reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to prevent severe climate change. The world emits around 50 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases each year [measured in carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2eq)].1

To determine how we can most effectively reduce emissions and what emissions can and can’t be eliminated with current technologies, we need to first understand where our emissions come from.

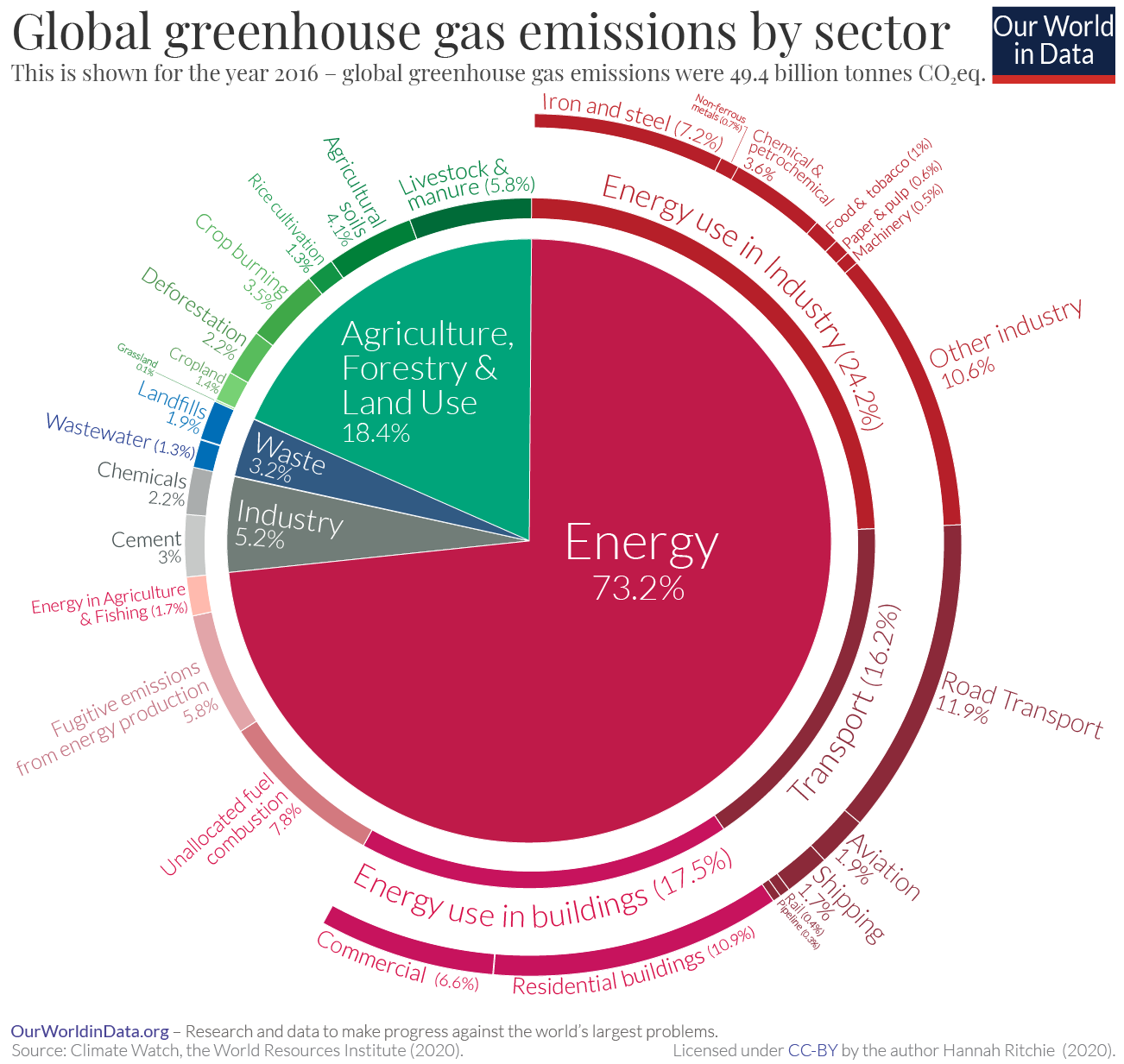

In this article, I present only one chart, but it is an important one — it shows the breakdown of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2016.2 This is the latest breakdown of global emissions by sector, published by Climate Watch and the World Resources Institute.3

The overall picture you see from this diagram is that almost three-quarters of emissions come from energy use; almost one-fifth from agriculture and land use [this increases to one-quarter when we consider the food system as a whole — including processing, packaging, transport, and retail]; and the remaining 8% from industry and waste.

I will briefly describe each sector category to learn what’s included in each. These descriptions are based on explanations provided in the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report AR5) and a methodology paper published by the World Resources Institute.45

Emissions come from many sectors: we need many solutions to decarbonize the economy

This breakdown clearly shows that a range of sectors and processes contribute to global emissions. This means there is no single or simple solution to tackle climate change. Focusing on electricity, transport, food, or deforestation alone is insufficient.

Even within the energy sector — which accounts for almost three-quarters of emissions — there is no simple fix. Even if we could fully decarbonize our electricity supply, we would also need to electrify all of our heating and road transport. And we’d still have emissions from shipping and aviation — which do not yet have low-carbon technologies — to deal with.

To achieve net-zero emissions, we need innovations across many sectors. Single solutions will not get us there.

Let’s walk through each of the sectors and sub-sectors in the pie chart, one by one.

[Clicking on this visualization will open it in higher resolution]

Download the data used in this visualization (.xlsx)

Energy (electricity, heat, and transport): 73.2%

Energy use in industry: 24.2%

Iron and Steel (7.2%): energy-related emissions from manufacturing iron and steel.

Chemical & petrochemical (3.6%): energy-related emissions from the manufacturing of fertilizers, pharmaceuticals, refrigerants, oil and gas extraction, etc.

Food and tobacco (1%): energy-related emissions from the manufacturing of tobacco products and food processing (the conversion of raw agricultural products into their final products, such as the conversion of wheat into bread).

Non-ferrous metals: 0.7%: non-ferrous metals contain very little iron. They include aluminum, copper, lead, nickel, tin, titanium, zinc, and alloys such as brass. Manufacturing these metals requires energy, which results in emissions.

Paper & pulp (0.6%): energy-related emissions from converting wood into paper and pulp.

Machinery (0.5%): energy-related emissions from the production of machinery.

Other industry (10.6%): energy-related emissions from manufacturing in other industries, including mining and quarrying, construction, textiles, wood products, and transport equipment (such as car manufacturing).

Transport: 16.2%

This includes a small amount of electricity (indirect emissions) and all direct emissions from burning fossil fuels to power transport activities. These figures do not include emissions from the manufacturing of motor vehicles or other transport equipment — this is included in the previous point, “Energy use in Industry”.

Road transport (11.9%): emissions from the burning of petrol and diesel from all forms of road transport which includes cars, trucks, lorries, motorcycles and buses. Sixty percent of road transport emissions come from passenger travel (cars, motorcycles, and buses), and the remaining forty percent is from road freight (lorries and trucks). This means that if we could electrify the whole road transport sector and transition to a fully decarbonized electricity mix, we could reduce global emissions by 11.9%.

Aviation (1.9%): emissions from passenger travel and freight, as well as domestic and international aviation. 81% of aviation emissions come from passenger travel, and 19% from freight.6 From passenger aviation, 60% of emissions come from international travel, and 40% from domestic.

Shipping (1.7%): emissions from burning petrol or diesel on boats. This includes both passenger and freight maritime trips.

Rail (0.4%): emissions from passenger and freight rail travel.

Pipeline (0.3%): fuels and commodities (e.g., oil, gas, water, or steam) often need to be transported (either within or between countries) via pipelines. This requires energy inputs, which results in emissions. Poorly constructed pipelines can also leak, leading to direct methane emissions to the atmosphere — however, this aspect is captured in the category “Fugitive emissions from energy production”.

Energy use in buildings: 17.5%

Residential buildings (10.9%): energy-related emissions from electricity generation for lighting, appliances, cooking, etc., and heating at home.

Commercial buildings (6.6%): energy-related emissions from generating electricity for lighting, appliances, etc., and heating in commercial buildings such as offices, restaurants, and shops.

Unallocated fuel combustion (7.8%)

Energy-related emissions from the production of energy from other fuels, including electricity and heat from biomass, on-site heat sources, combined heat and power (CHP), the nuclear industry, and pumped hydroelectric storage.

Fugitive emissions from energy production: 5.8%

Fugitive emissions from oil and gas (3.9%): fugitive emissions are often accidental methane leakages to the atmosphere during oil and gas extraction and transportation from damaged or poorly maintained pipes. This also includes flaring — the intentional burning of gas at oil facilities. Oil wells can release gases, including methane, during extraction — producers often don’t have an existing network of pipelines to transport it, or it wouldn’t make economic sense to provide the infrastructure needed to capture and transport it effectively. However, under environmental regulations, they need to deal with it somehow: intentionally burning it is often a cheap way to do so.

Fugitive emissions from coal (1.9%): fugitive emissions are the accidental leakage of methane during coal mining.

Energy use in agriculture and fishing (1.7%)

Energy-related emissions from using machinery in agriculture and fishing, such as fuel for farm machinery and fishing vessels.

Direct Industrial Processes: 5.2%

Cement (3%): carbon dioxide is produced as a byproduct of a chemical conversion process used in the production of clinker, a component of cement. In this reaction, limestone (CaCO3) is converted to lime (CaO), and produces CO2 as a byproduct. Cement production also produces emissions from energy inputs — these related emissions are included in “Energy Use in Industry”.

Chemicals & petrochemicals (2.2%): greenhouse gases can be produced as a byproduct from chemical processes — for example, CO2 can be emitted during the production of ammonia, which is used for purifying water supplies, cleaning products, and as a refrigerant, and used in the production of many materials, including plastic, fertilizers, pesticides, and textiles. Chemical and petrochemical manufacturing also produces emissions from energy inputs — these related emissions are included in “Energy Use in Industry”.

Waste: 3.2%

Wastewater (1.3%): organic matter and residues from animals, plants, humans, and their waste products can collect in wastewater systems. When this organic matter decomposes, it produces methane and nitrous oxide.

Landfills (1.9%): landfills are often low-oxygen environments. When organic matter decomposes, it converts to methane.

Agriculture, Forestry, and Land Use: 18.4%

Agriculture, Forestry, and Land Use directly account for 18.4% of greenhouse gas emissions. The food system as a whole—including refrigeration, food processing, packaging, and transport—accounts for around one-quarter of greenhouse gas emissions. We look at this in detail in our article on the greenhouse gas emissions of food production.

Grassland (0.1%): when grassland becomes degraded, these soils can lose carbon, converting to carbon dioxide in the process. Conversely, carbon can be sequestered when grassland is restored (for example, from cropland). Therefore, emissions refer to the net balance of these carbon losses and gains from grassland biomass and soils.

Cropland (1.4%): depending on the management practices used on croplands, carbon can be lost or sequestered into soils and biomass. This affects the balance of carbon dioxide emissions: CO2 can be emitted when croplands are degraded or sequestered when restored. The net change in carbon stocks is captured in emissions of carbon dioxide. This does not include grazing lands for livestock.

Deforestation (2.2%): net carbon dioxide emissions from changes in forestry cover. This means reforestation is counted as “negative emissions” and deforestation as “positive emissions”. Net forestry change is, therefore, the difference between forestry loss and gain. Emissions are based on lost carbon stores from forests and changes in carbon stores in forest soils.

Crop burning (3.5%): the burning of agricultural residues — leftover vegetation from crops such as rice, wheat, sugar cane, and other crops — releases carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane. Farmers often burn crop residues after harvest to prepare land for the resowing of crops.

Rice cultivation (1.3%): flooded paddy fields produce methane through a process called “anaerobic digestion”. Organic matter in the soil is converted to methane due to the low-oxygen environment of water-logged rice fields. 1.3% seems substantial, but it’s important to put this into context: rice accounts for around one-fifth of the world’s supply of calories and is a staple crop for billions of people globally.7

Agricultural soils (4.1%): nitrous oxide — a strong greenhouse gas — is produced when synthetic nitrogen fertilizers are applied to soils. This includes emissions from agricultural soils for all agricultural products — including food for direct human consumption, animal feed, biofuels, and other non-food crops (such as tobacco and cotton).

Livestock & manure (5.8%): animals (mainly ruminants, such as cattle and sheep) produce greenhouse gases through a process called “enteric fermentation”. When microbes in their digestive systems break down food, they produce methane as a by-product. This means beef and lamb tend to have a high carbon footprint, and eating less is an effective way to reduce the emissions of your diet.

Nitrous oxide and methane can be produced from the decomposition of animal manures under low oxygen conditions. This often occurs when large numbers of animals are managed in a confined area (such as dairy farms, beef feedlots, and swine and poultry farms), where manure is typically stored in large piles or disposed of in lagoons and other types of manure management systems. “Livestock” emissions here include direct emissions from livestock only — they do not consider impacts of land use change for pasture or animal feed.

Endnotes

Carbon dioxide-equivalents try to sum all of the warming impacts of the different greenhouse gases together to give a single measure of total greenhouse gas emissions. To convert non-CO2 gases into their carbon dioxide-equivalents, we multiply their mass (e.g., kilograms of methane emitted) by their “global warming potential” (GWP). GWP measures the warming impacts of a gas compared to CO2; it basically measures the “strength” of the greenhouse gas averaged over a chosen time horizon.

While it would be ideal to have more timely data, this is the most recent data available at the time of writing (September 2020).

The World Resources Institute also provides a nice visualization of these emissions as a Sankey flow diagram.

In its 5th Assessment Report (AR5), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provided a similar breakdown of emissions by sector. However, this was based on data published in 2010. The World Resources Institute, therefore, provides an important update of these figures.

IPCC (2014): Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Baumert, K. A., Herzog, T. & Pershing, J. (2005). Navigating the Numbers: Greenhouse Gas Data and International Climate Policy, World Resources Institute.

Graver, B., Zhang, K., & Rutherford, D. (2019). CO2 emissions from commercial aviation, 2018. The International Council of Clean Transportation.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that the average daily supply of calories from all foods was 2,917 kilocalories in 2017. Rice accounted for 551 kilocalories [ 551 / 2917 * 100 = 19% of the global calorie supply]. It supplied 26% of calories in China and 30% in India.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2020) - “Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-ghg-emissions-by-sector,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {Sector by sector: where do global greenhouse gas emissions come from?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2020},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.