Democracy

Democracy is broadly understood to mean ‘rule by the people’.

In practice, it is often defined as people choosing their leaders in free and fair elections.

Other definitions go beyond this. For example, some of them see democracy as people having additional individual rights and being protected from the state.

Democracy gives citizens the right to influence important decisions over their own lives and allows them to hold their leaders accountable.

But it can have other benefits too: democratic countries seem better governed than autocracies, seem to grow faster, and foster more peaceful conduct within and between them.

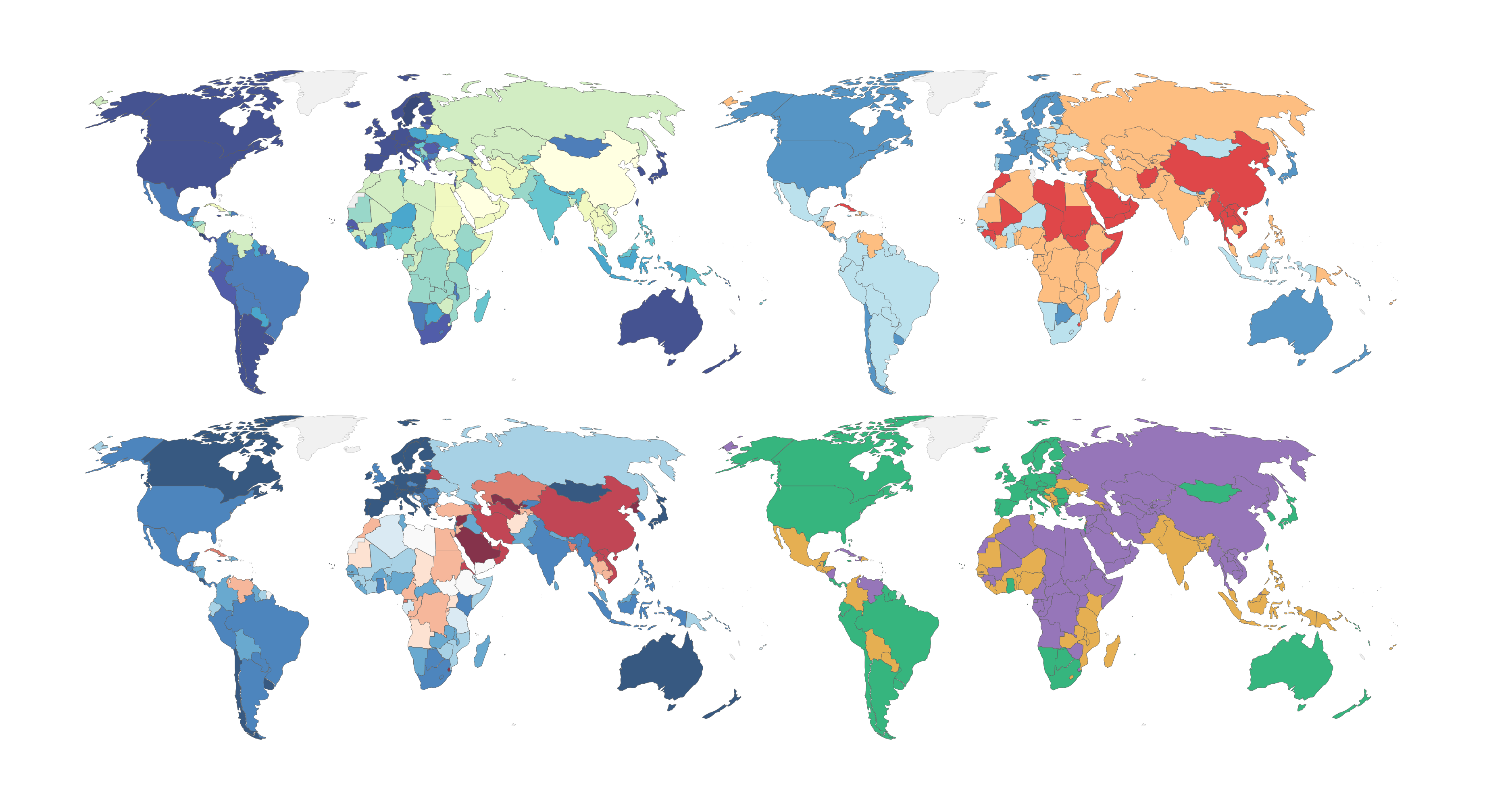

On this page, you can find data, visualizations, and writing on how democracy has spread across countries, how it differs between them, and whether we are moving towards a more democratic world.

Explore Data on Democracy

This explorer seeks to make data on democracy easier to access and understand. It provides and explains data from eight leading democracy datasets: their main democracy measures, indicators of specific characteristics, and global and regional overviews. You can learn more about the approaches — and which democracy measure may be best to answer your questions — in our article explaining how researchers measure democracy:

Democracy data: how sources differ and when to use which one

There are many ways to classify and measure political systems. What approaches do different sources take? And when is which approach best?

Research & Writing

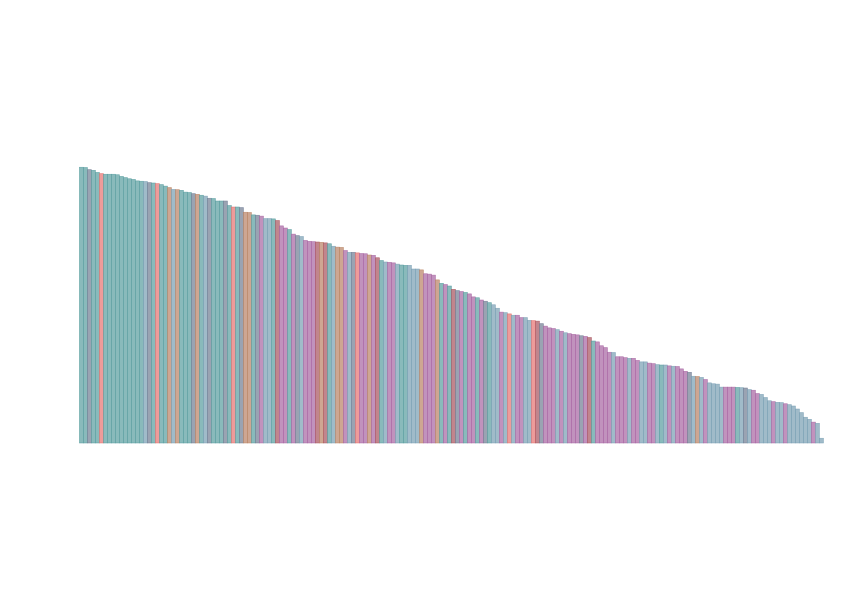

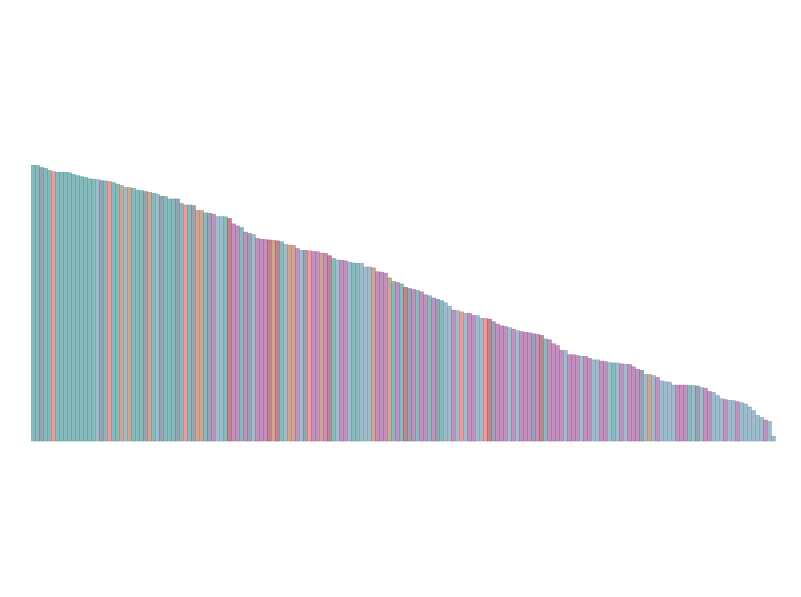

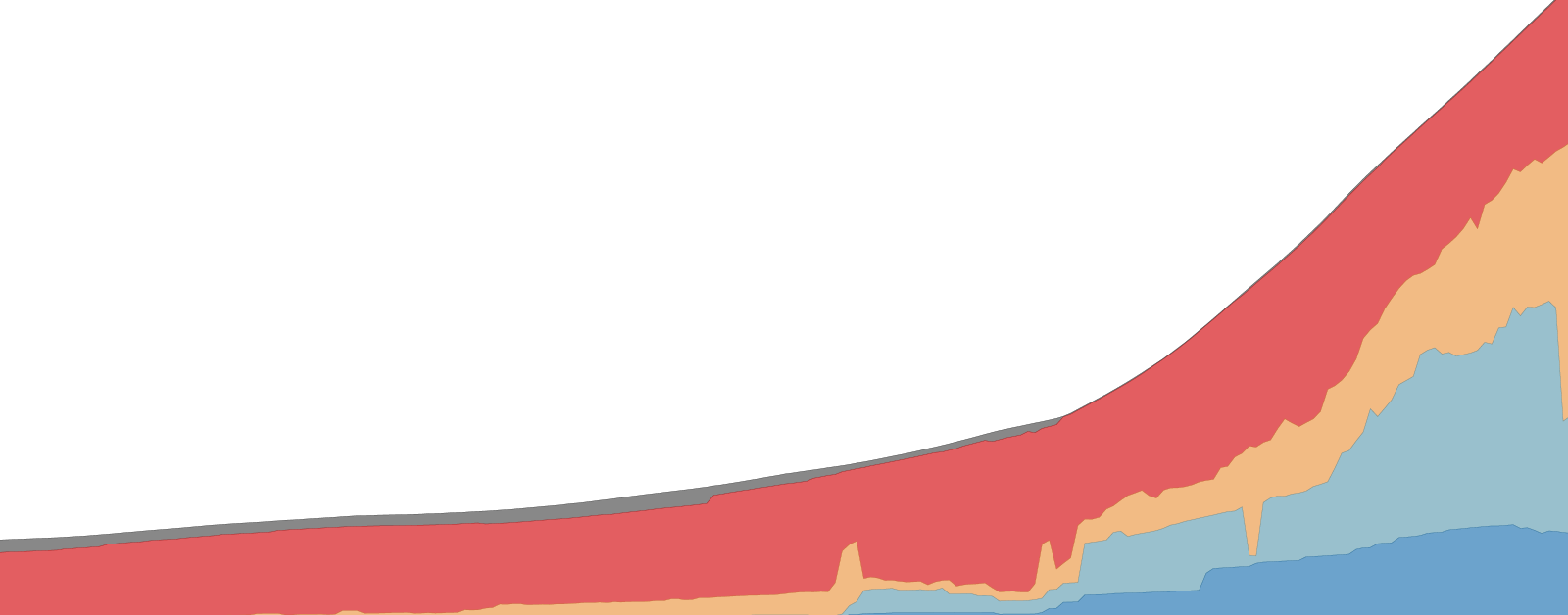

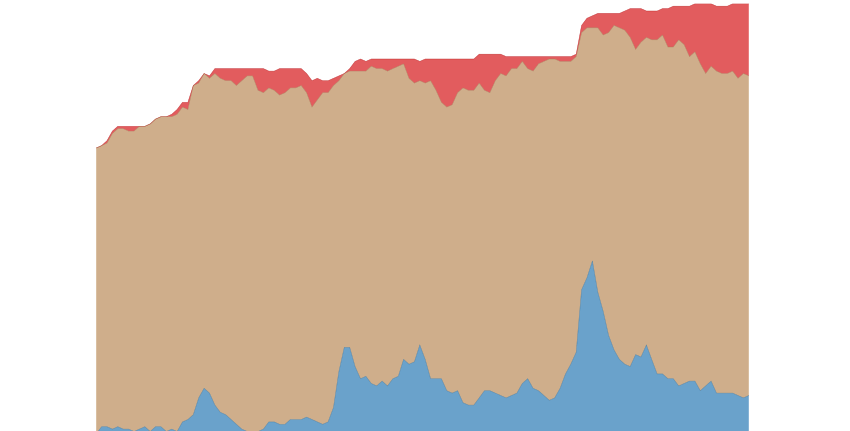

200 years ago, everyone lacked democratic rights. Now, billions of people have them

Half of all countries are democracies. But how many people enjoy democratic rights?

The world has recently become less democratic

Many more people have democratic rights than in the past. Some of this progress has recently been reversed.

Measuring Democracy

Endnotes

The United Kingdom and the United States were the only countries that could be classified as electoral autocracies, because its political leaders were chosen through elections, but citizens lacked additional freedoms to make those elections free and fair.

Examples are France and New Zealand.

Examples are Australia, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Lührmann, Anna, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan Lindberg. 2018. Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes. Politics and Governance 6(1): 60-77.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, M. Steven Fish, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Adam Glynn, Ana Good God, Sandra Grahn, Allen Hicken, Katrin Kinzelbach, Joshua Krusell, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Natalia Natsika, Anja Neundorf, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Josefine Pernes, Oskar Rydén, Johannes von Römer, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Aksel Sundström, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, Steven Wilson and Daniel Ziblatt. 2023. V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

RoW’s reclassification is the result of recent changes in the V-Dem data, which identify declines in the autonomy of the election management body, the freedom and fairness of elections, and especially the freedom of expression, the media, and civil society. You can read more in V-Dem’s 2021 annual report Autocratization Turns Viral.

Edgell, Amanda, Seraphine Maerz, Laura Maxwell, Richard Morgan, Juraj Medzihorsky, Matthew Wilson, Vanessa Boese, Sebastian Hellmeier, Jean Lachapelle, Patrik Lindenfors, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan Lindberg. 2022. Episodes of Regime Transformation Dataset (v13). Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Based on ERT, a country is autocratizing from when V-Dem’s electoral democracy index decreases by 0.01, until the score increases or remains unchanged for four years, and the total decrease between the start and end amounts to a decrease of at least 0.10. Democratizing countries are classified analogously. We exclude Ukraine from 2002 to 2004 and El Salvador from 2015 and 2017 because for them democratizing and autocratizing episodes happen to overlap.

Seraphine Maerz, Amanda Edgell, Matthew Wilson, Sebastian Hellmeier, Staffan Lindberg. 2021. A Framework for Understanding Regime Transformation: Introducing the ERT Dataset. Varieties of Democracy Institute: Working Paper No. 113. University of Gothenburg.

This means, however, that some countries are not classified as autocratizing even though their score visibly declines. One example is the United States in the 2010s, whose decline between 2015 and 2020 fell just barely short of the ERT threshold.

Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. On democratic backsliding. Journal of Democracy 27(1): 5-19.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

Bastian Herre, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser (2013) - “Democracy” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/democracy' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-democracy,

author = {Bastian Herre and Lucas Rodés-Guirao and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser},

title = {Democracy},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2013},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/democracy}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.